Work-life balance

The Medicaid calculus behind Donald Trump’s tax cuts

Republicans want to save billions through Medicaid work requirements. Millions could lose coverage

HOW REPUBLICANS will find enough budget savings to pay for tax cuts is the political maths question of 2025.

One of the most important calculations involves Medicaid, a government health programme for poor and disabled Americans.

The problem is that Donald Trump has promised not to touch it, and on May 12th, he also vowed to lower prescription-drug prices.

His populism on health benefits complicates the work of congressional Republicans.

A proposal from a committee that oversees Medicaid steers clear of the deepest cuts that had been debated in Washington, but it nonetheless seeks large savings by imposing work requirements on Medicaid recipients who are unemployed.

Together with a hotch-potch of other money-saving schemes, the committee’s approach would reduce the deficit by $715bn over the next ten years, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), a non-partisan scorekeeper.

But it would also cause 8.6m fewer Americans to have health insurance by 2034.

That trade-off raises two questions about the budget fight ahead.

Will the president accept any plan that forces millions of low-income people off Medicaid?

And are work requirements—long a fixture of conservative thinking on social benefits—a viable fix?

Today Medicaid provides health coverage for 71m Americans, 20m more than 15 years ago.

The Affordable Care Act fuelled that growth but has also supercharged the price of the programme: in 2024 it made up 3.2% of GDP, up from 2.6% in 2010.

The point of instituting work requirements would be both to cut health-care spending and to push people into work.

The House plan would make recipients aged 19 to 64 do 80 hours of work, job training or volunteering per month from 2029.

There would be various exemptions for those with dependents or disabilities.

The policy has public backing—although cutting Medicaid in general is deeply unpopular, six in ten Americans support adding work requirements.

The problem is less with the principle than with the implementation.

To start, very few people who receive Medicaid do not work.

Creating a policy that targets these people but does not sweep up others is hard.

During Mr Trump’s previous term Arkansas experimented with requirements and the results were messy.

People had to report their working hours every month or risk losing their insurance.

By the time a judge put a stop to the programme, 18,000 people had lost their coverage.

Researchers found that most of those were still eligible; they had just missed or messed up their paperwork.

Among those who lost Medicaid, half reported serious problems paying off medical debt and almost two-thirds delayed taking medicines because of cost.

Health-care providers said that it was the neediest, such as disabled and homeless people, who were left uncovered.

And for all that, there was not even an increase in employment in the 18 months after the change.

This problem of policy design is not unique to Arkansas.

In 2023 the CBO found that a House Republican plan for work requirements would not increase employment.

It would save money, however.

The Commonwealth Fund, a think-tank, estimated gains of about $500bn over ten years—or roughly a third of the overall budget cuts that Republicans are seeking.

The allure of work requirements is “more of a political thing”, says Tom Scully, who led the Centre for Medicare and Medicaid Services under George W. Bush.

It feeds an ideological urge that Medicaid should not be an entitlement, he says.

Work requirements have plenty of support at the state level too.

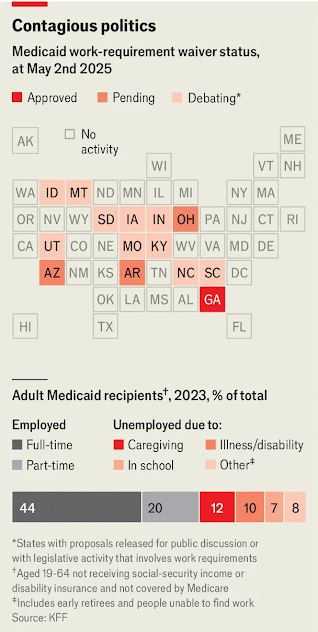

Since Mr Trump re-entered office, 13 states have started proposing their own schemes through waivers that make policy experiments possible (see map).

Expand and contract

Big federal subsidies incentivise expanding Medicaid, but ten states have not done that, in part because of the welfare-state connotations of such a move.

That stigma may fade as MAGA builds a political coalition grounded in working-class communities that rely on benefit programmes.

Chris Pope of the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think-tank, sees work requirements as “sweetening the pill” for such laggard red states, making it easier for their leaders to sell a flip-flop to voters.

Mr Pope reckons that work requirements might end up increasing Medicaid spending, as more states expand the programme.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario