The Sahel’s Triangle of Insecurity

In Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, Islamist extremist groups are growing as Russian assistance falters.

By: Ronan Wordsworth

U.S. Africa Command chief Gen. Michael Langley issued a stark warning in late May while addressing African defense chiefs in Nairobi.

He said the Sahel is now the world’s “epicenter of terrorism” and that the most serious terrorist threats to the U.S. homeland are emerging from Africa.

His remarks were particularly directed at the three members of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) – Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger – each of which has expelled Western security forces and embraced Russian support.

A recent surge in attacks in the three countries underscores the region’s accelerating collapse and the growing strength of jihadist groups.

The fallout is global, affecting European security, foreign investment and international stability.

Terrorism’s Epicenter

For nearly 15 years, Islamist extremist groups have targeted Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

In response, the U.N. launched the G5 Sahel mission, deploying a 10,000-strong counterterrorism force, while France independently launched Operation Barkhane to bolster local governments and contain jihadist expansion.

Though flawed, the operations stopped the groups’ spread and severely diminished their capabilities.

In time, however, military coups in all three countries brought juntas to power, prompting the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to suspend them from the group.

Undeterred, the new leaders garnered popular support by promising to restore order and eliminate jihadist threats.

They expelled U.N. security forces, including French and U.S. troops, in favor of Russian forces and paramilitaries, notably the Wagner Group.

But as ties with ECOWAS deteriorated, these regimes grew more isolated.

Recently, insurgent violence has started rising again – led by Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in Sahel Province (ISSP) – while the region’s capacity to contain it has diminished.

May was among the deadliest months ever in the Sahel, with more than 400 military casualties.

The morale of local military forces is collapsing, while JNIM and ISSP – bolstered by looted weapons and new recruits – have shifted their targeting from rural areas to administrative centers and population hubs, signaling greater confidence and ambition.

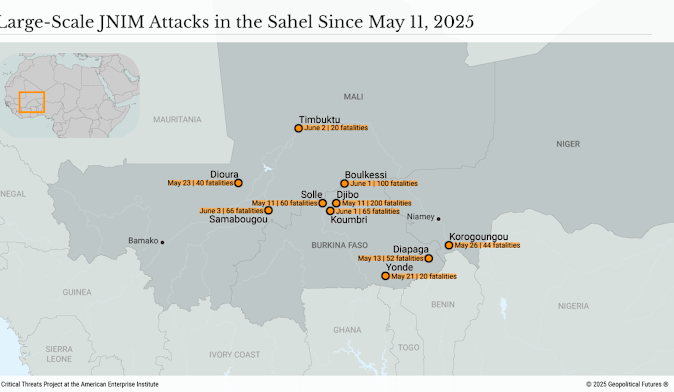

Since May 11, JNIM attacks have killed at least 20 civilians, soldiers or allied militiamen on 10 separate occasions, mostly in Mali and Burkina Faso.

Major attacks in Mali during the month of May left more than 300 soldiers dead or wounded, including one attack that nearly reached the capital and another that overran checkpoints and supply bases in Timbuktu.

In Burkina Faso, JNIM temporarily seized two provincial capitals, looting weapons and vehicles before retreating.

The Burkinabe government controls just 30-40 percent of the country.

ISSP has been similarly active, primarily in Niger, and is increasingly threatening neighboring Benin and Nigeria.

ECOWAS has called for a coordinated response, but the AES states prefer to lean on Russian support.

Military responses have been ineffective and at times even counterproductive, as indiscriminate violence against local populations – particularly among Fulani and Tuareg communities – fuels jihadist recruitment.

Attacks are becoming more frequent, coordinated and lethal, and there is little evidence this trajectory will change.

Russia’s capacity to offer more assistance is limited, while the leaders of the AES states have ruled out reconciliation with Washington, Paris and Brussels.

They created a joint 5,000-troop force, equipped with air and intelligence assets, but it is hampered by poor coordination and infrastructure.

Without Western assistance, the force also lacks air support and satellite surveillance.

The junta leaders, who tied their legitimacy to promises of restoring security, are increasingly reliant on coercion and Russian protection to stay in power.

Fearing a coup, the junta in Burkina Faso has purged senior military ranks and harshly repressed civil society, including sending dissidents to fight on the front lines.

Surprisingly, however, the juntas enjoy broad support in the capitals thanks to Russian information operations, which spread anti-Western narratives, advocate pan-African resistance, obscure battlefield losses and promote the junta leaders – particularly Ibrahim Traore of Burkina Faso.

Meanwhile, insecurity threatens to spill over into neighboring countries.

For example, ISSP and Boko Haram have launched attacks in northern Nigeria, then retreated to Niger’s Great Lakes region, where the government has no control.

The situation is serious enough that Nigeria’s defense chief proposed closing the border and erecting a barrier.

In Benin, JNIM has been fighting for coastal access to strengthen its logistics network, killing more than 50 soldiers in the process.

Algeria and Morocco have increased patrols along the Malian border to prevent spillover.

Border forces in Morocco and fairly stable states like Mauritania are also supported by European and U.S. troops.

Russian Interests

Russian interests in the region are threefold.

First, there is the economic payoff.

In the 12 months up to December 2023, the Kremlin reportedly earned more than $2.5 billion selling African gold, often through opaque channels to evade sanctions.

Wagner pioneered this model, providing regime protection in exchange for access to mining licenses.

It has since been copied by other Russian private military companies, all of which are increasingly under Moscow’s direct control.

The Sahel is rich in gold, uranium and other resources.

In Burkina Faso, the junta granted Russian firm Nordgold a license to exploit the Niou gold deposit (estimated to be worth billions of dollars), yet the deal is projected to earn the Burkinabe government less than $90 million.

Elsewhere, junta leaders have bullied Western firms and revoked mining rights under the pretext of resource nationalization.

For example, in Mali, the government detained senior staff of Canada’s Barrick Gold and Australia’s Resolute Mining and demanded hundreds of millions of dollars for unpaid taxes.

In June, the government also put Barrick’s Loulo-Gounkoto mine, which had been shut since January, under state control.

(The company’s 2025 output forecast excluded the mine, indicating that it does not expect an improvement.)

In Niger, French company Orano has been blocked from operating or exporting uranium from its mine and is now trying to sell the assets amid interest from Russian and Chinese firms.

Second, Russia uses its position to rally supporters and amplify anti-Western narratives in global forums such as the United Nations.

In an effort to stoke resentment in the Global South, Moscow pushes false claims that the U.S., Britain, France and even Ukraine are to blame for the rise of jihadism.

Finally, the Sahel forms a new axis of Russian influence stretching from West Africa to the Red Sea, giving Moscow leverage over migration routes, mineral flows, arms smuggling and regional blocs.

Russia can threaten to destabilize the region further, or even weaponize migration, to pressure Europe in any future negotiations.

Russia does nearly all this through private military companies that it increasingly controls.

A case in point is Wagner, which announced earlier in June that it had completed its mission in Mali and was returning home.

In fact, the security situation is rapidly deteriorating, and Wagner personnel are being replaced by Africa Corps, a paramilitary group that reports to the Russian Ministry of Defense.

The Kremlin planned this transition years ago, but close personal ties between some Wagner personnel and Mali’s junta leaders, combined with Africa Corps’ lack of legitimacy, forced it to wait.

Gradually, Africa Corps absorbed more and more of Wagner’s structure, enabling it to take over.

Though other states – China and Turkey among them – have stakes in the region, they lag far behind Russia’s influence.

China has been cautious, intervening diplomatically to protect its assets – as it did when Benin closed the border and stopped the flow of oil through the China-operated Niger-Benin oil pipeline – but otherwise avoiding deeper involvement.

Conversely, Turkey’s SADAT paramilitary group has tried to emulate the Wagner model but has failed to convince the military juntas in the Sahel of its reliability.

Meanwhile, a Turkish intelligence office that was being set up in Niger’s capital was expelled for ineffectiveness.

Outlook

The situation, already unstable, is devolving, and Moscow has limited power or ambition to address it.

Just six months ago, Moscow failed to support Bashar Assad as he lost control of Syria, a much more strategically important regime than any in the Sahel.

Nevertheless, Africa Corps is recruiting for assignments in the Sahel, offering salaries and bonuses far above the Russian average.

For the three junta leaders, the outlook is bleak: expanding jihadist groups, heightened risks of coups and isolation from any powers with the resources and will to help.

Their resort to indiscriminate ethnic violence, backed by Russian forces, is fueling enemy recruitment, while their own recruitment and morale are flagging.

Washington and Brussels are increasingly alarmed.

JNIM and ISSP are routing government forces and looting their arsenals, and financing operations through the illicit trade of gold and other precious minerals, making them more dangerous.

As Langley warned, these groups are now the most credible transnational threats to Europe and the United States.

Burkina Faso saw the most terrorist casualties of any country last year, and the AES trio accounted for more than half of global terrorism-related deaths.

Despite this, the current U.S. administration is questioning the relevance of Africa Command, and the AES regimes remain hostile toward the West.

Rather than direct involvement, therefore, Western powers will likely concentrate on shoring up other states in the region, such as Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal and the Gulf of Guinea states.

The AES countries will be left to Moscow.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario