Arise, consumers!

As Donald Trump’s trade war heats up, China is surprisingly confident

Should it be?

FOR THE second time in less than a decade, the world’s biggest importer is pummelling the world’s biggest exporter with tariffs.

On April 2nd America landed its biggest blow yet, raising the average levy on Chinese goods above 60%.

Yet the mood in Beijing is not one of panic.

In response to Donald Trump’s first term as president, Xi Jinping, China’s leader, initiated a campaign to reduce China’s economic dependence on America.

Chinese officials are hoping that a revival in domestic demand, after four years of property troubles and two years of deflation, can cushion the blow from Mr Trump’s war on trade.

As proof that consumers are cheering up, Li Qiang, China’s prime minister, has pointed to Ne Zha 2, an animated film that smashed box-office records during the Spring Festival holiday.

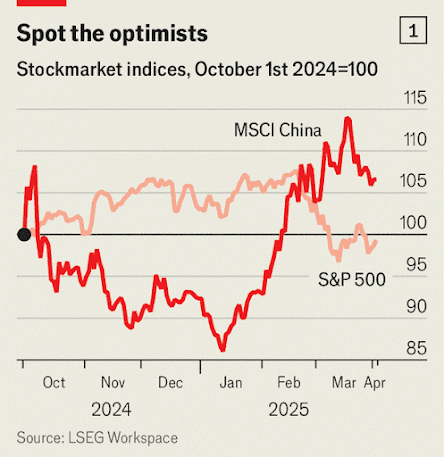

Whereas American investors have recoiled at their new government’s protectionism, sending the S&P 500 down by nearly 4% so far this year, the MSCI China index is up by 15% (see chart 1).

China has lots of experience of Mr Trump.

His first administration punished China for obliging American firms to hand over intellectual property, under a legal provision, Section 301, that allows the president to act against countries that abuse international trade.

A seven-month inquiry concluded that China’s extraction of technology had cost America at least $50bn a year.

Mr Trump’s team therefore slapped tariffs on a similar sum of Chinese imports, from arc lamps to chicken incubators.

When China retaliated with levies of its own, America upped the ante.

By the end of the tussle, America had imposed tariffs on roughly two-thirds of Chinese goods.

At its worst, the war reduced China’s GDP by as much as 0.8%, according to Goldman Sachs, a bank.

America also almost crippled one of the country’s leading telecoms companies, ZTE, by denying it access to American technology, before Mr Trump spared it as a personal “favour” to Mr Xi.

The president’s team later targeted Huawei, an even bigger icon, which America deemed a threat to national security.

Urgent divergence

Since then, China has tried to become less beholden to America as either a market for its wares or as a supplier of vital technologies.

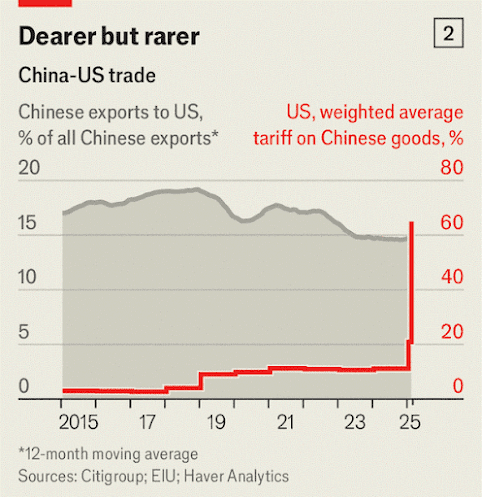

It now sells less than 15% of its exports to America, down from almost a fifth in 2017.

Its tech companies are also more robust.

Huawei has shown that it can produce surprisingly snazzy semiconductors, despite the efforts of both Mr Trump and Mr Biden to deny it access to advanced chips and chipmaking equipment.

DeepSeek, a Chinese AI firm, can almost match the best Western large language models at a fraction of the cost.

When Mr Xi met global CEOs in Beijing on March 28th, his chest was out: the message was, China’s technological prowess is greater than ever.

Unfortunately, Mr Trump’s second trade shock will be much stronger than the first.

He had already raised tariffs on Chinese goods by 20 percentage points since returning to power, lifting the average rate above 30% (see chart 2).

On April 2nd he said he will raise tariffs by another 34 points.

He also removed a loophole that allowed packages worth less than $800 to escape duties.

Further imposts may be on the way.

America might, for instance, charge ships built in China an extra fee for docking in its ports.

Trump thump

Mr Trump’s ultimate goals are obscure.

America’s president has painted tariffs as bargaining chips to win concessions from trading partners.

On March 26th, for instance, he floated the possibility of reducing tariffs if China permits the sale of TikTok, a Chinese-owned short-video site that is popular in America.

A few days earlier Steve Daines, a senator and emissary of Mr Trump, told one of China’s deputy prime ministers that trade talks were not possible until China stemmed the flow of fentanyl precursors into the Americas.

Mr Trump has also described tariffs variously as a source of revenue, a means to attract investment in manufacturing, and a way to eliminate trade deficits, which he regards as robbery.

Even if China is eventually able to negotiate some degree of relief, few in Beijing expect a deal to be struck soon.

Worse, some of the safety-valves that helped China before are unlikely to work as well this time.

When tariffs rose in 2018, China redirected many of its exports to countries like Taiwan and Vietnam.

They bundled Chinese components into goods for final sale in America.

That dodge may be more difficult in the new war, because Mr Trump is slapping tariffs on all of America’s big trading partners.

China also fears a “tariff cascade”, points out Fred Neumann of HSBC, a bank.

If Mr Trump’s levies divert Chinese exports from America to other markets, those other countries might impose duties of their own on China.

Many countries already have their finger on the trigger.

According to WTO statistics, 66 anti-dumping investigations were initiated against China in the first half of 2024 alone, more than in the whole of 2023.

Even Russia, China’s “no-limits” friend, has acted to stem the flow of Chinese cars into the country.

To win goodwill, China has removed tariffs on imports from many of the world’s poorest countries.

A government researcher argues that China should also woo Europe with unilateral measures to boost trade and revive a long-stalled investment agreement.

European diplomats say there is little substance to China’s charm offensive so far.

The two parties are still arguing about electric vehicles.

In the face of higher tariffs, a weaker currency could help China’s exporters maintain market share, especially in price-sensitive industries.

But the central bank has kept the yuan steady against the dollar.

It does not want a sharp depreciation to antagonise other countries or trigger destabilising capital outflows, as happened in 2015.

It may also have a more strategic motive.

A weaker currency would muffle the impact of tariffs on the dollar price of Chinese goods, sparing American buyers some pain.

China may be understandably reluctant to save America from the consequences of its own folly.

China’s government has warned exporters not to give in to American pressure on prices.

Local customs officials have been monitoring invoices, says an executive at a Chinese exporter based in Shanghai.

They want to discourage anything that “undermines their ability to cause inflation in America”.

Inflation may soon be the least of America’s worries.

Many fear it is headed for a sharp slowdown.

Indeed, the final reason why the second trade war could be worse for China than the first is a little counterintuitive: America looks more fragile this time.

In 2018 it grew robustly even as the trade war raged.

Now American consumer confidence is dropping precipitously.

The stockmarket is listing.

Some leading indicators already pointed to negative growth in the first quarter of the year, even before Mr Trump’s tariff bombshell.

Chinese officials may smirk at the prospect of a recession in America.

But a state researcher notes that American demand for Chinese goods is far more sensitive to changes in income than to changes in price.

Nimble exporters may be able to dodge American tariffs, he says, but there is no escaping an American recession.

With the outlook for exports becoming more forbidding, China’s domestic economy will have to take up the slack.

That might seem unlikely, even laughable.

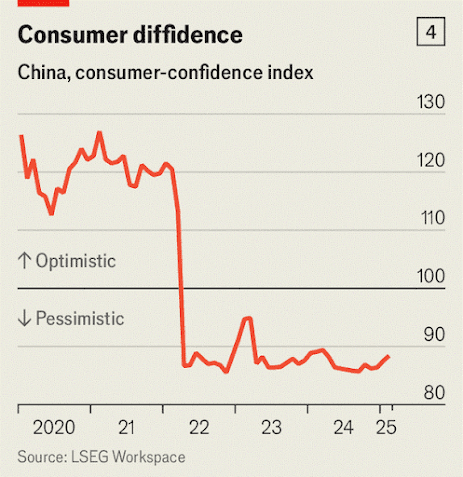

In recent years China has been hobbled by a painful property crisis, strained local-government finances, a crackdown on big tech firms and shattered consumer confidence.

Mr Xi has been painfully slow to respond to these problems—probably because he is the cause of many of them.

But in the past six months, policy has begun to turn in a more promising direction.

The government has pledged to arrest the fall in the property market and “vigorously” boost household consumption.

It is giving local governments more room to borrow.

Mr Xi and other Communist Party officials are signalling that private enterprise is back in favour and that foreign investment is welcome.

Serendipitously, innovation in AI is also racing ahead, potentially fostering growth.

Reviving the property market is the first step.

In 2020-21 the central government orchestrated a credit crunch meant to halt the unsustainable expansion of the sector.

It succeeded all too well.

Most large developers have since buckled under the pressure.

Prices tumbled and demand for homes collapsed.

Sales of residential floorspace have halved since 2021.

Property and allied industries once accounted for roughly a quarter of China’s GDP.

Its collapse has therefore reverberated throughout the economy.

The slowdown in building hit labour markets and the myriad industries that feed into construction, such as glass and steel.

Not even the government was spared.

Because local authorities relied heavily on land sales for revenue, their ability to provide services and counteract the downturn was constrained.

Ordinary people have also been victims.

Homeowners’ net worth shrank on paper, denting their willingness to spend.

In Shenzhen, the country’s sparkling southern tech hub, average home prices fell by nearly 20% between 2021 and 2023.

Tens of millions of families have also paid upfront for homes that have never been built by cash-strapped developers.

The good news for the Communist Party, however, is that the worst of the housing crisis appears to be behind it.

Sales volumes are falling less steeply now than a year ago.

Prices in some large cities, such as Shanghai and Nanjing, have started to rise again.

Some analysts believe national prices will stabilise by early next year.

Some government researchers argue that the deflation of the property bubble was both desirable and inevitable.

Even the timing was good.

China succeeded in popping the bubble in the brief interval between the two trade wars.

If property speculation had been allowed to continue growing unchecked, only to collapse as tariffs soared, the outcome would have been much worse.

Long-suffering local governments have also been given more relief this year.

They have been allowed to raise an additional 6trn yuan ($830bn) in bonds over three years to refinance riskier “hidden” liabilities that often lie on the balance-sheets of the investment vehicles they sponsor.

They can also issue a record 4.4trn yuan in “special bonds” this year, up from 3.9trn yuan last year.

These funds can be used to pay off arrears to companies and employees and even buy land.

That should get more money circulating in some of the worst-off places.

China’s many local governments are, after all, both big employers and big consumers of goods and services in their own right, says Yao Yang, an economist.

They may underpin as much as 30% of domestic consumption.

The financial woes of China’s local government have provoked a broader shift in the party’s thinking on economic policy.

In September its powerful 24-member Politburo promised to stabilise the property market and strengthen “counter-cyclical” measures.

At the annual meeting of China’s legislature in March, the government unveiled additional borrowing amounting to about 2% of GDP in 2025.

Some of that extra money will be spent building better infrastructure, a habitual priority.

But an unusually large chunk will be funnelled to households.

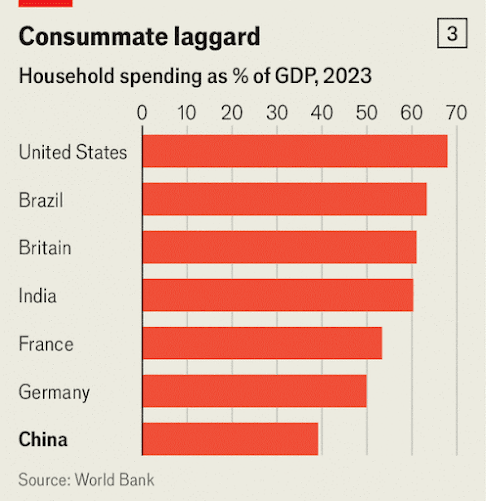

Their consumption accounts for only about two-fifths of GDP in China, compared with around a half to two-thirds in most other big economies (see chart 3).

“Vigorously” boosting this share ranked first among ten pressing tasks for the government this year, above Mr Xi’s cherished goals of modernising industry and becoming more self-reliant in technology.

To this end, the government has doubled the size of its trade-in scheme for consumer goods such as cars and household appliances, now worth 300bn yuan.

It has also broadened its scope to include smartphones and other electronics.

Civil servants’ pay has been raised, as has the miserly pension available to city folk who do not work and rural residents.

More generous financial aid for students and bigger subsidies for health insurance are also promised.

In a 30-point plan released a few days after the legislative meeting, officials pledged to raise the minimum wage and expand child-care subsidies.

Local governments have begun to respond.

Hohhot, the provincial capital of Inner Mongolia, has said that it will give families 10,000 yuan upon the birth of their first child, five annual 10,000 yuan payments for a second child, and ten more for a third child.

If this sort of scheme were rolled out nationally, it would put about 400bn yuan a year into parents’ pockets, according to one calculation.

The hope is that such measures will give people more money to spend and at last revive their confidence to spend it (see chart 4).

At the same time, the party has tried to revive the private sector’s animal spirits.

A meeting between Mr Xi and a handful of entrepreneurs, including Jack Ma, a previously disgraced billionaire, has brought cheer.

Mr Ma had been the most famous victim of a crackdown on tech companies, including his e-commerce group, Alibaba, in 2020.

The meeting has been seen as a sign that the Communist Party is ready to succour rather than denigrate private business once again.

The valuations of many of China’s biggest tech companies have soared in response.

Alibaba’s share price is up by 60% since the start of the year.

The increase comes from a low base.

But there is good reason to be excited.

A wave of AI exuberance has swept the country since January, as DeepSeek’s models have dramatically lowered the cost of the new technology.

Its breakthrough has also demonstrated that Chinese tech firms can innovate and thrive despite heavy American export restrictions on semiconductors.

Early evidence suggests that Chinese adoption of AI is proceeding apace.

The party is encouraging both private firms and arms of government to embrace AI.

By one estimate roughly half of the demand for DeepSeek’s model comes from the state.

Flappable capital

All these measures will help, but more will be needed.

Improved sentiment, visible in the stockmarket, will take time to percolate through the economy.

Mr Xi’s rehabilitation of Mr Ma will not be enough to reassure entrepreneurs, says an adviser to senior officials: “Too much has happened in the past five years.”

Some cash-strapped local governments have imprisoned businessmen to shake them down.

A continuing crackdown on investment banking has seen salaries slashed and some celebrity financiers disappear.

And even when the authorities are not hounding private investors, they are crowding them out: the government is easily China’s biggest provider of private equity and venture capital.

China’s stockmarket regulator, meanwhile, has stalled most IPOs, creating a backlog of investors keen to cash out.

All this leaves the private sector wary of the hype around AI and of the government’s newfound appreciation for entrepreneurship.

More money will be needed as well as more charm.

The stimulus unveiled last month should be enough to stop deflation getting worse, but it will not dispel the danger altogether.

And it leaves China with little margin for safety.

Officials have said they stand ready to do more if need be.

“The central government has kept sufficient tools and policy space in reserve,” said Lan Fo’an, the finance minister, in early March.

It will “introduce new incremental policies when necessary”, assured Mr Li, the prime minister, a few weeks later.

China cannot afford such hesitancy when Mr Trump shows none.

There is little to suggest that Mr Xi has fundamentally changed his views about how the economy works.

His acceptance of the importance of consumption and private enterprise is presumably more tactical than heartfelt.

But in the aftermath of a property bust and amid another trade war, even he must recognise that investment and exports cannot be the economic engines they were.

For two decades economists have urged China to embrace consumption-led growth.

If, having exhausted the alternatives, it at last does so, it will be making a virtue of a perilous moment.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario