Mexico Considers a New Foreign Policy Path

Voters must soon decide between two competing approaches.

By: Geopolitical Futures

On June 2, Mexican voters will go to the polls to select their next president.

At a time when the dominant geopolitical players around the world are looking to leverage ties with the Global South, the two leading candidates in the race are advocating different visions for Mexico’s foreign policy going forward.

Both candidates have proposed strategies that seek to take advantage of the global economic and political restructuring taking place and boost development in parts of the country that have been left behind.

But there’s a debate over whether to continue with Mexico’s inward-focused, non-interventionist approach or adopt a more assertive global posture.

The former prioritizes stability while the latter would involve taking greater risks for potential long-term benefits.

Mexico’s ties to the international system are shaped by its geographic position and dominated by economic relations.

Located in the southern half of North America, it has privileged access to the U.S. market and an extensive list of potentially profitable trade agreements.

It’s among the 15 largest economies in the world and has impressively managed its post-pandemic recovery with one of the highest economic growth rates in Latin America.

Due to its proximity to the U.S., Mexico has benefited from the U.S.-China trade war that began in 2018.

And due to the lessons learned during the pandemic about supply chain vulnerabilities, U.S. and European companies have been increasingly interested in Mexico for their nearshoring efforts.

This global restructuring, coupled with recent changes in Mexican politics, has prompted a reevaluation of the country’s foreign policy approach.

Many countries, including the U.S., have expressed a desire to reorient international supply chains, which raised questions in Mexico over whether it could replicate the success of other fast-growth export-oriented countries and renewed calls for structural changes.

In addition, the growing importance of the Global South increased opportunities for Mexico to position itself as a key international player and a bridge between emerging economies and global powers.

Another focal point of the debate is whether Mexico should diversify its trade partnerships or focus on its competitive advantages with its dominant partner, the United States.

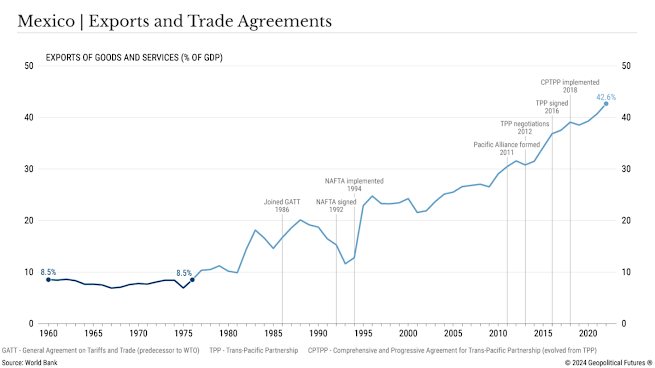

This debate began prior to the pandemic, as Mexico, like many other economies, pursued a pivot to Asia that included signing up in 2012 for the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement and joining in 2011 the Pacific Alliance, which aims to foster ties between member states and Asian markets.

Meanwhile, Mexico is also facing serious threats to its national stability stemming from the dominance of criminal groups in certain areas of the country and in a significant segment of the economy.

Many believe the solution lies in economic development measures that can help the central government reclaim power in vulnerable regions and thus reestablish national order.

These measures, and the government’s ability to implement them, are inevitably linked to trade.

The current debate marks a drastic shift from Mexico's traditional foreign policy, characterized by protectionist policies.

Its historically cautious approach was a result of decades of instability between 1810 and 1877, as well as the crises it suffered from during the Mexican Revolution’s resulting conflicts between 1910 and 1927.

In the decades that followed, the country carefully forged ties with key foreign nations but refused to overcommit, politically or economically, to any single power because foreign influence had in the past led to social unrest, internal conflict and external interventions.

Its goal in limiting its interactions was to ensure the central government held control over national politics, the workforce, wealth and key economic sectors.

This is also why Mexican trade was long limited to the export of commodities, mainly oil, and represented less than 10 percent of gross domestic product for much of the 20th century.

Mexican governments also abstained from engaging in global affairs or conflicts for fear of opening itself up to foreign criticism and incursions, particularly given its own vulnerabilities, most notably its weak military and economy.

In the 1980s and 1990s, however, Mexico became more open to foreign trade and investment, motivated largely by a multiyear debt crisis.

The desire to attract investment prompted economic and political reforms, which severed the old power structure’s control by creating autonomous institutions, generating a separation of powers and introducing a free market economy.

The idea was that reduced government spending and intervention in the economy would make the country more attractive to foreign capital.

In 1986, Mexico joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the predecessor to the World Trade Organization, and in 1992, it signed NAFTA, building the basis for a new export- and market-oriented economic model.

This led to decreased dependence on oil exports and a surge in manufactured goods exports.

However, the reforms of the late 20th century, as well as those implemented under Enrique Pena Nieto’s administration in 2012-2018, did not completely eliminate the traditional power structure.

Its remnants still challenge initiatives for deeper institutional reforms by fomenting social unrest amid growing economic pressures.

In the current election campaign, two competing foreign policy approaches have emerged.

The governing Morena party’s candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum, supports a cautious approach, aiming to limit global powers’ influence in Latin America and maintain a neutral stance on international affairs.

Economically, Sheinbaum accepts the continuation of certain elements of the old system, such as state-owned companies, government involvement in the natural resource sector, and inward-focused policies.

She seeks to balance this with some economic and financial incentives to keep Mexico attractive to outside investors and, in doing so, take advantage of the international economic restructuring.

However, this path faces significant challenges from the middle class and power groups that stand to gain from pivoting to a new economic and trade model.

The opposition candidate, Xochitl Galvez, has called for a more outward focus.

She seeks to boost investment and trade through further fiscal, economic and political reforms that would increase the country’s competitiveness and role in the world economy.

The opposition has also said it’s willing to double down on the country’s alignment with the United States, including by providing diplomatic support for Washington against Eurasian powers (namely, Russia) and challenging pro-Russian regimes in the region.

In the short term, this approach could spark domestic tensions and political upheaval, especially involving certain interest groups, like unions, nongovernmental organizations and big corporations, that profit from a more traditional strategy.

Mexico’s historical weakness and need to address domestic challenges have forced governments in the past to focus on internal matters, limiting Mexico’s engagement abroad and keeping it from investing too heavily in trade, as Asia-Pacific countries have done.

Mexico is now deciding its future trajectory, weighing whether to pave a new path and risk confrontation with other global economies for the promise of long-term gains or keep the status quo in favor of maintaining stability.

Andres Araujo was the author of this report. Mr. Araujo is an intern at Geopolitical Futures and a student at the University of Valle de Atemajac in Guadalajara, Mexico, where he studies international relations.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario