China Signals Economic Policy Changes

A major summit in July will focus on local government debt and sputtering growth.

By: Victoria Herczegh

Senior Chinese officials are signaling that Beijing will announce a significant adjustment in the country’s economic strategy in July during a key meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Committee.

At the end of April, the Politburo promised prudent monetary and proactive fiscal policies to goose demand, help struggling firms and tackle “risks and hidden dangers.”

Days earlier, a prominent government adviser, Liu Yuanchun, warned about supply-demand imbalances and an unexpectedly rapid deterioration of the local government debt situation.

President Xi Jinping should prepare the public for more modest economic growth in the years ahead, Liu added.

Chinese government advisers rarely discuss the country’s economic problems so candidly.

It is also highly unusual for the Central Committee to hold its Third Plenary Session, which focuses on economic issues and is typically where important reforms are unveiled, outside of the fall season.

In fact, the plenum in July was originally supposed to occur around October 2023.

These factors point to a high likelihood that important changes are on the way.

However, the roots of the problems in the Chinese economy likely run deeper than the potential reforms will go.

As Liu intimated, the problem of worsening local government debt levels seems to have caught Beijing by surprise.

Outstanding local government debt was within the budget limit at the end of last year, according to the head of the Chinese central bank, who reassured the public that the government had the situation under control.

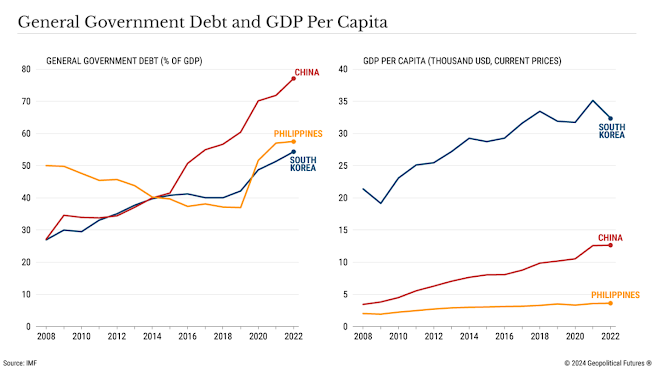

On the other hand, the International Monetary Fund warned that China’s general government gross debt reached 88.6 percent of gross domestic product at the start of 2024, an increase since 2019 of nearly 47 percent.

The same figure among advanced economies climbed by just 7 percent over the same period.

At the center of the local government debt mess are local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), companies that borrow on behalf of provinces, municipalities and cities to keep debt off their books.

LGFVs have played a vital role in recent decades helping local governments finance mostly infrastructure projects.

But even as the use of LGFVs in China has roughly quadrupled in the past decade, LGFV lending has only rarely paid for itself, leading off-balance-sheet debt to pile up.

Moreover, since the mid-2010s, Chinese LGFVs have tried to boost their earnings through land sales or leases.

When the Chinese real estate market stalled beginning in 2021, so did that earnings strategy.

If LGFVs started to default, it would stress the balance sheets of many Chinese banks, widen credit spreads and put downward pressure on the yuan.

For Beijing, it’s a game of whack-a-mole.

In recent months, after Chinese regulators tightened rules for onshore debt issuances, local governments started exploiting a loophole that enables them to borrow from wealthy Chinese people and institutions via offshore bonds.

January saw the highest-ever monthly volume of offshore debt issuances by Chinese local governments.

The offshore market makes up less than 5 percent of total LGFV debt, but Beijing is worried that the cross-border borrowing maneuver is undermining efforts to rein in debt.

Regulators are expected soon to tighten restrictions for LGFVs looking to issue bonds offshore.

Earlier this year, regulators advised LGFVs to stop issuing offshore bonds with a 364-day duration.

Regulators also instructed some of the heavily indebted provinces to slow down or even stop certain state-funded infrastructure projects, including a highway in Yunnan province and a tunnel in Gansu province.

Other affected areas were the municipalities of Tianjin and Chongqing and the provinces of Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Guizhou, Ningxia and Qinghai – all identified as high-risk thanks to their debt levels.

These efforts make it even more difficult for China to reach the 5 percent growth target this year, and given the state of government debt, they won’t make much of a difference anyway.

It’s been clear for some time that China’s economy isn’t going to grow like it did in the mid-2010s.

In April, for example, Fitch revised its outlook for China’s A+ credit rating from stable to negative, citing things similar to what Liu Yuanchun alluded to: rising risks to the country’s public finances.

To achieve even moderate but stable growth, structural issues like local government debt will need to be managed.

Since last fall, the central government has made multiple efforts to support local governments, allowing them to borrow funds for a year ahead and issuing 1 trillion yuan ($138 billion) in government bonds for natural disaster relief, but no significant improvement followed.

The fact that the leadership has been closely monitoring the country’s less wealthy Western regions – and the fact the president himself has conducted personal inspections of the poorest provinces – shows just how nervous Beijing is about financially motivated political unrest.

For China, it is easy for economic problems to become political ones, especially if the conflict is between the central government and municipalities.

Xi and his Cabinet understand as much, as evidenced by the statements about “hidden dangers in key areas” and their announcements of new aid measures.

Earlier this spring, the central government pledged to issue $139 billion of ultralong special treasury bonds.

(This was a major move that turned a tool meant to manage crises into a regular source of funding.)

It has also approved “special refinancing bonds” for local governments and called on banks to provide these bonds to municipalities in need.

At the third plenum, Beijing is expected to officially announce a new goal of moderate growth and measures commensurate to that end.

The new measures will likely target local governments, boosting much-needed domestic demand and even potentially easing some of the country’s strict trading practices to woo foreign investment.

The fact that the third plenum was scheduled alongside a noticeable shift in government rhetoric indicates certainty in Beijing of the changes that need to be made.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario