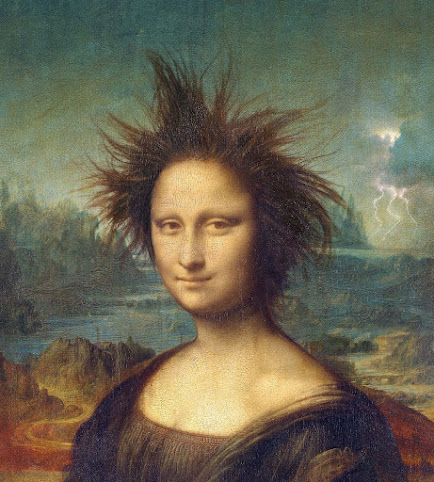

Squeeze, surge, slap

The triple shock facing Europe’s economy

After the energy crisis, Europe faces surging Chinese imports and the threat of Trump tariffs

Europe is not known for its dynamism, but today it looks stagnant by any standard.

Frazzled by the energy shock that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the European Union’s economy has grown by only 4% this decade, compared with 8% in America; since the end of 2022, neither it nor Britain has grown at all.

If that were not bad enough, Europe faces a surge of cheap imports from China which, while benefiting consumers, could harm manufacturers and increase social and industrial strife.

And within a year Donald Trump could be back in the White House, slapping huge tariffs on Europe’s exports.

The timing of Europe’s misfortune is bad.

The continent needs strong growth in order to help fund more defence spending, especially since American support for Ukraine has dried up, and to meet its green-energy goals.

Its voters are increasingly disillusioned and liable to back hard-right parties such as the Alternative for Germany.

And long-standing drags on growth—a fast-ageing population, overbearing regulators and inadequate market integration—have not gone away.

There is a frenzy of activity in European capitals as governments try to respond.

They must take care.

Although the shocks facing Europe originate abroad, errors from Europe’s own policymakers could greatly aggravate the damage.

The good news is that the energy shock is past the moment of maximum pain: gas prices have fallen far from their peak.

Unfortunately the others are just beginning.

Faced with a deflationary slowdown, China’s government should be stimulating the country’s paltry household consumption, which could replace property investment as a source of demand.

Instead President Xi Jinping is using subsidies to supercharge Chinese manufacturing, which already accounts for about a third of global goods production.

He is relying on foreign consumers to prop up growth.

China’s focus is on green goods, most significantly electric vehicles, for which its global market share could double, to a third, by 2030.

That would end the dominance of Europe’s national champions like Volkswagen and Stellantis (whose largest shareholder, Exor, part-owns The Economist’s parent company). From wind turbines to railway equipment, Europe’s manufacturers are nervously looking eastward.

After November manufacturers might look westward, too.

Last time he was in office Mr Trump imposed tariffs on steel and aluminium imports, eventually including those from Europe, leading the eu to retaliate against motorbikes and whiskey until an uneasy truce was struck under President Joe Biden in 2021.

Today Mr Trump threatens a 10% blanket tariff on all imports; his advisers talk of going further.

Another round of the trade war threatens Europe’s exporters, which had €500bn ($540bn) of sales in America in 2023.

Mr Trump is obsessed with bilateral trade balances, meaning that the 20 (of 27) eu member states with a goods-trade surplus are natural targets.

His team is also aggrieved by Europe’s digital levies, its carbon border tax and its value-added taxes.

What should Europe do?

The path ahead is littered with traps.

One error would be to keep economic policy too tight at a moment of vulnerability—a mistake the European Central Bank has made before.

In recent years the bank has rightly fought inflation with interest-rate increases.

But in contrast to free-spending America, Europe’s governments are bringing their budgets into better balance, which should cool the economy, while cheap Chinese goods will bring down inflation directly.

That gives Europe’s central banks room to cut interest rates to support growth.

It will be easier to cope with disruption from outside if central banks keep the economy out of a slump that would stop displaced workers finding new jobs.

Another trap would be to copy America’s and China’s protectionism by unleashing vast subsidies on favoured industries.

Subsidy wars are zero-sum and squander scarce resources—within Europe, countries have already started an intra-continental race to the bottom.

China’s recent economic woes demonstrate the flaws, not the virtues, of excessive government planning; America’s industrial policy has not wowed voters in the way President Biden had hoped, and tariffs have cost more jobs than they have produced.

By contrast, trade makes economies richer even when their trading partners are protectionist.

A manufacturing boom in America is a chance for European producers to supply parts; cheap imports from China will make the green-energy transition easier and provide relief to consumers who suffered during the energy crisis.

Selective and proportional retaliation against protectionism may be justified in an attempt to dissuade America and China from further disrupting global trade flows.

But it would come at a cost to Europe’s economy, as well as hurting its intended targets.

Instead Europe should forge its own economic policy fit for the moment. As America showers industry with public money, Europe should spend on infrastructure, education, and research and development.

Instead of emulating China’s interventionism, Europe should note the benefit Chinese firms derive from a vast domestic market.

Integrating Europe’s market for services, where trade remains difficult, would help firms grow, reward innovation and replace some lost manufacturing jobs.

The EU should reform its burdensome and fragmented regulation, which also holds back service industries.

Unifying capital markets—including those in London—would have the same effect.

European diplomats should sign trade deals wherever they are still on offer, rather than letting farmers hold them up, as in several recent negotiations.

Linking electricity grids would make the economy more resilient to energy shocks and smooth the green transition.

Don’t double down

Such an open agenda in a protectionist age may seem naive.

But it is deep, open markets that have the potential to boost Europe’s growth as the world changes around it.

As the shocks strike, policymakers must stay grounded in that reality.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario