Is China’s Economy Finally Bottoming Out?

Recent data contains clear hints of improvement. But the Fed, for one, could play spoiler.

By Nathaniel Taplin

While there is some good news, China’s job market and property sector still look weak. PHOTO: CFOTO/ZUMA PRESS

While there is some good news, China’s job market and property sector still look weak. PHOTO: CFOTO/ZUMA PRESSBetter late than never: After a rough 2023 and early 2024, the first read on China’s economy in March points to a tentative rebound heading into the second quarter.

Data released over the weekend showed China’s official factory purchasing managers index in March moving back above the 50-point level separating expansion from contraction for the first time since September.

The services sector index notched its strongest reading since June, and a separate factory gauge from Caixin and S&P Global hit a 13-month high.

The good news is the improvement is probably real: Exports and the global electronics sector seem to be on the mend again, and looser Chinese credit markets are helping support investment.

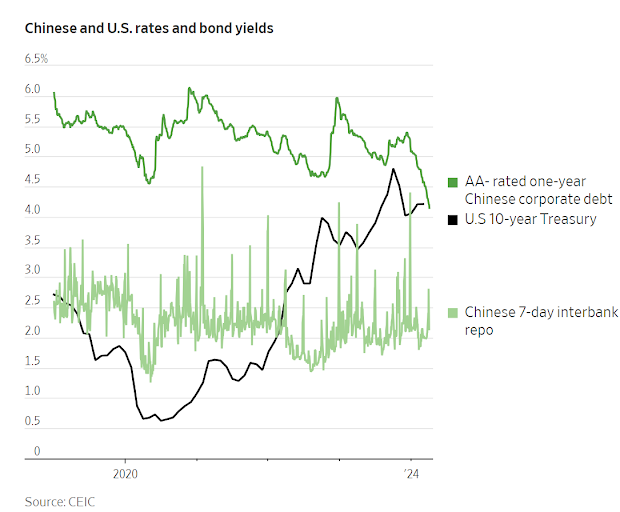

The bad news is that Beijing still seems very nervous about letting the yuan fall too far, and U.S. rates are rebounding again.

That could make further significant monetary stimulus much trickier.

And China’s job market and property sector still look weak.

Growth of around 5% for 2024, the official target, still looks like a big reach.

Even so, there is no denying China’s recent monetary easing—especially the big cut to banks’ reserve requirement ratios effective in early February—seems to be working.

After a long period in which borrowing costs looked much too high for the economy’s health as a whole, credit markets have begun to noticeably improve in recent weeks, particularly for lower-rated borrowers.

Yields on three-month, AA-minus-rated corporate debt have fallen by a full 0.6 percentage points since mid-February, according to figures from data provider CEIC.

Chinese government-bond yields are down significantly too, although by much less.

At the same time, exports have begun looking healthier.

China’s official export orders PMI subindex jumped to a 13-month high of 51.3 in March—a rise that was echoed in the privately compiled Caixin survey.

Seasonal factors including the end of the Lunar New Year may be one reason.

But the global electronics sector has also been recovering of late, and U.S. consumers have been feeling less grumpy, at least according to some measures: The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index hit its highest level since mid-2021 in March.

China’s economy is teetering on the brink of widespread deflation—a scenario that could cause even more problems than high inflation.

No surprise then to see China’s manufacturing investment beginning to bounce back a bit more convincingly: Overall factory investment rose nearly 10% year over year in January and February.

Investment in computer and communication-equipment manufacturing was up nearly 15%.

For 2023 as a whole, those figures were 6.5% and 9.3% respectively.

There are also some reasons to doubt that momentum will be sustained.

Short-term interbank rates have jumped again noticeably since late March, a period that also saw a renewed rise in U.S. Treasury yields and inflation data, and a selloff in the yuan.

If China’s central bank starts tightening liquidity again at the margins to defend the yuan, factory sector investment might lose steam.

Just as important, the improvement in the headline official PMI readings last month wasn’t mirrored in the employment subindexes, and the housing sector data for January and February still looked weak.

With the job and property markets still in the doldrums, China’s economy needs all the help it can get from a supportive central bank and exports.

If the Fed delays rate cuts, at least one of those props might not stick around.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario