How Gulf states are putting their money into mining

Hungry to diversify their economies beyond fossil fuels, Middle Eastern powers are investing in the resources needed to produce clean energy

Harry Dempsey in London and Chloe Cornish in Dubai

Abu Dhabi royal Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed al-Nahyan, left, and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman © FT montage/Getty Images

Abu Dhabi royal Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed al-Nahyan, left, and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman © FT montage/Getty ImagesIn the summer of 2023, Rothschild bankers working for Zambia’s government were close to finalising a shortlist of buyers for a prized copper mine.

Mopani, a troubled but rare asset formerly owned by resources giant Glencore, had drawn offers worth hundreds of millions of dollars from big names in the mining world eager to gain access to a metal that is crucial to clean energy technologies of the future.

The list had been narrowed down to China’s Zijin Mining and South African deep-level excavation expert Sibanye-Stillwater when seemingly out of nowhere came a third contender: an obscure company from the United Arab Emirates called International Resources Holding.

But behind the scenes IRH’s parent, International Holding Company, the $240bn business empire of powerful Abu Dhabi royal Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed al-Nahyan, had been courting the highest levels of Zambia’s government for nearly two years.

By December, IRH had agreed to buy a 51 per cent stake in the mine for $1.1bn and overnight became the industry’s fastest-moving newcomer in decades.

“What stood out . . . was their intention to invest in the mining industry,” says a Zambian official who was among those tasked with nurturing the budding relationship.

“They were head and shoulders above in terms of what they were able to facilitate.”

The Mopani deal finalised at the end of March marks a new force sweeping through the global mining sector.

Gulf nations, hungry to diversify their economies beyond fossil fuels, are redirecting petrodollars to secure copper, nickel and other minerals used in power transmission lines, electric cars and renewable power.

Beyond the UAE, chief among them is Saudi Arabia which wants mining to contribute $75bn to its economy by 2035, up from $17bn.

Oman has started construction of what could be the world’s largest green steel plant that plans to use iron ore from Cameroon, while the Qatar Investment Authority, the gas-rich state’s sovereign wealth fund, is now Glencore’s second-biggest shareholder.

“The region has huge potential to create a major mining industry,” says Tom Harley, managing director of Dragoman, a mining advisory working with Gulf nations.

“The Saudis are so palpably ambitious: even if they achieve 60 per cent of what they are after, then it will be enormous.”

For resource-rich nations in Africa, Asia and Latin America, the entrance of these middle powers into the critical minerals battleground is a welcome alternative to decades of exploitative arrangements underpinned by either western colonialism or Chinese debt.

Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema told the Financial Times in March that “anyone who knows what risk management is all about wants to see that we are not putting our eggs into one basket”.

These nations believe that selling to Gulf states can help sidestep tension between the US and China over their copper, iron ore and lithium — resources the two powers need to electrify their economies.

“Getting investment from the Middle East gives relief from being seen to be in favour of one region or the other,” the Zambian official explains.

Schoolchildren walk past part of the Mopani copper mine site in Kitwe, Zambia. An obscure UAE company last year struck a deal for the mine, which was formerly owned by Glencore © Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg

Schoolchildren walk past part of the Mopani copper mine site in Kitwe, Zambia. An obscure UAE company last year struck a deal for the mine, which was formerly owned by Glencore © Waldo Swiegers/BloombergBut Gulf investment also comes with risk, industry insiders warn.

Sovereign wealth can bring opacity and complexity when what mining projects and local communities desperately need is more accountability and transparency.

Despite this, Washington has welcomed the Gulf’s expanding role in mining for helping to break Beijing’s monopoly over processing critical minerals.

The US has been actively brokering Saudi, Emirati and Qatari investment in riskier jurisdictions, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, where western companies struggle to enter, in order to keep China out, according to executives from mining companies and trading houses, as well as a senior US government official.

For international mining groups also seeking to navigate US-China tensions over natural resources, the Middle East offers a neutral venue for minerals processing, capital and corporate headquarters.

SRG Mining, a graphite miner caught in a political firestorm in Canada over a failed plan to collaborate with China’s C-One, announced in February that it would move to the UAE.

“[The Gulf states] trade openly with the US and Chinese.

It’s cards face up,” says Mark Cutifani, chair of Vale Base Metals, a copper and nickel producer that Saudi Arabia bought a 10 per cent stake in last year for $2.6bn.

“We’re a Brazilian company run out of Canada joint venturing in Indonesia with the Chinese and the Saudis have 10 per cent in us.

Welcome to the next stage of the political complexity of the world we live in.”

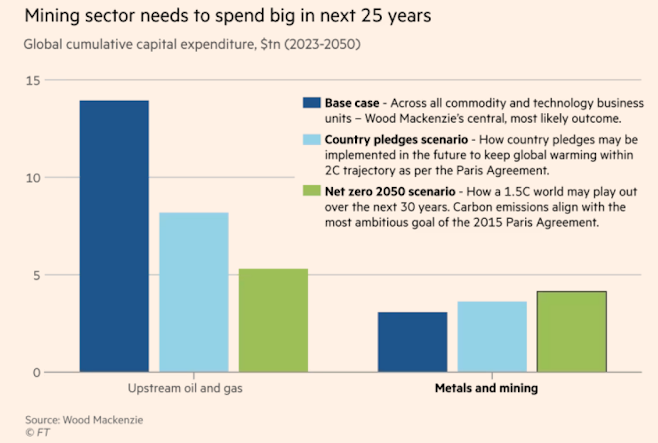

To meet global climate change targets — by building solar power, turning car fleets electric and bolstering electricity grids — about $4.1tn needs to be spent on mining, refining, and smelting critical minerals, according to consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

With Gulf nations raking in $400bn of fossil fuel revenues annually, but facing a future where hydrocarbons will be phased out, expanding into mining is a logical step.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are investing heavily in new technologies and will need access to their own steady supply of raw materials.

“The Middle East is looking to diversify and has a war chest,” says Richard Blunt, partner at Baker McKenzie, the law firm that represented Zambia on the IRH deal.

“They’ve got this massive advantage as they can do government-to-government deals and have patient capital yet come without the diplomatic pinch involved in choosing between Chinese and western investors.”

Under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s “Vision 2030” to modernise Saudi Arabia’s economy, mining and minerals processing are earmarked to become the third industrial “pillar” next to oil and gas and petrochemicals.

“Nation building” is the main driver behind Saudi’s push, says Tim Keating, a former head of mining for the Oman Investment Authority.

Saudi Arabia is gearing up to exploit what it estimates are $2.5tn of domestic mineral assets with the help of the world’s largest oil exporter, Saudi Aramco, alongside state mining group Ma’aden.

But reaping the fruits of exploration will take years, if not more than a decade.

Hurdles include a lack of water in the mainly desert country, few trained mining engineers and scant high-quality mineral deposits.

“We now have the largest exploration programme in the world,” said Yasir al-Rumayyan, governor of Saudi’s Public Investment Fund, at the Future Minerals Forum mining conference in Riyadh in January.

“But we don’t have all the kinds of minerals that we need for our future initiatives.”

To address that, the kingdom aims to secure copper, iron ore, lithium and nickel from overseas for processing domestically through Manara Minerals, a joint venture established last year between Ma’aden and the Public Investment Fund.

In return for minority investments into established operations run by blue-chip companies such as BHP and Rio Tinto, it aims to receive metals supply — a model Japanese trading houses have successfully deployed for decades.

Gulf cash — and the political cover — will allow industry giants to make riskier investments.

For example, the world’s second largest gold producer, Barrick Gold, is courting Saudi and Qatari interest in a $7bn copper project in a western Pakistan province plagued by insurgents — the kind of hazardous environment that most investors would steer clear of.

Mark Bristow, Barrick Gold’s chief executive, says that western fund managers’ demand for dividends has “crimped” the industry’s appetite for growth, leaving the mining sector desperate for long-term financing.

The Gulf’s involvement is “going to help us open up frontiers,” he adds.

Through such investments, the kingdom hopes to position itself at the centre of a “super region” spanning Africa, central Asia and south Asia.

In January, Saudi signed deals to explore mining projects with Egypt, Russia, Morocco and the DRC.

By wielding its cheap, abundant energy, it can process the raw materials from resource-rich nations starved of finance to manufacture products such as steel or electric cars for rapidly growing consumer markets in India, for example.

The UAE is also keen to advance its strategic objectives through mining.

Thani bin Ahmed Al Zeyoudi, the UAE’s minister of state for foreign trade, says that it is pursuing “government to government” engagement on minerals and that there is “a lot of focus on the African continent”.

The emirate of Dubai, a key precious metals trading hub, already has a large foothold in Africa’s ports and logistics network, the fortunes of which are closely tied to commodities.

Dubai government-owned DP World has won port concessions in DRC and most recently Tanzania’s Dar es Salaam, a crucial shipping juncture for copper from Zimbabwe and Zambia.

“The majority of these resources are landlocked.

There’s a huge opportunity to reduce the cost of the supply chain,” says Mohammed Akoojee, head of sub-Saharan Africa at DP World, which hopes to double the capacity of its terminals business in the next three to five years, including expanding bulk shipping.

Much like the Chinese, the Gulf states are promising resource-rich nations an investment package centred around mining; Zambia expects the UAE to invest in agriculture, tourism and energy.

Leon Coetzer, chief executive of Jubilee Metals, a London-listed miner partnering with IRH to process copper from waste material at Mopani, says that “they can bring together a consortium of investment in infrastructure, power, health and logistics alongside mining”.

Bringing “an ecosystem of investment” is particularly important for African countries, he adds.

The Dar es Salaama harbour, a key shipping juncture. The port was the subject of a deal between Tanzania and Dubai last year that boosted the emirate’s foothold in Africa’s logistics networks © Charles Bowman/Pics Editorial/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

But there are worries that the Gulf states could replicate the hazy resources-for-infrastructure deals advanced by Beijing through its Belt and Road Initiative that had mixed outcomes in the global south.

Many countries have been left deeply indebted and some projects have stalled.

“The speed of the IRH deal doesn’t bode well for navigating those complexities,” says Thomas Scurfield, senior economist at the Natural Resource Governance Institute, a non-profit.

“It’s supposed to be an alternative to the Chinese model but may ultimately have many parallels.”

Ebrony Peteli, a former miner living in Mufulira, a town home to Mopani pits and a critical smelter, was elated to hear about new investors coming to reinvigorate a mine that once drove regional prosperity but now employs a mere 4,000 people, a third of its workforce in the 1990s by his estimates.

That happiness has since given way to scepticism after learning that IRH is an untested player only founded in 2022.

“There’s no transparency,” he says.

“Who are we dealing with?”

His concerns are echoed by others in Mufulira, who want to know who at IRH is responsible for Mopani, whether they will employ local subcontractors and what its plans are to safeguard the local community, which has suffered from the smelter’s pollution for years.

This will become more pressing if IRH forges ahead with a tremendous worldwide growth plan.

A company profile it sent to the FT says it is seeking to set up operations in “Indonesia, Angola, Kenya, Tanzania, Chile [and] Peru”.

In Zambia, as well as its Mopani mine, IRH has announced plans to bid for a stake in the Lubambe copper mine, owned by China’s JCHX Mining.

IRH intends to take a controlling stake in Konkola Copper Mines, which the government handed back to India’s Vedanta in September, according to people familiar with IRH’s strategy.

Vedanta says that it wants to remain majority owner but would be open to selling a 20 per cent stake.

The Zambian government has also said it is open to a third investor in KCM.

Slag flows from trucks at a nickel processing site in Indonesia. Gulf states are redirecting petrodollars to secure investments in minerals used in green technology such as electric cars © Mast Irham/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Slag flows from trucks at a nickel processing site in Indonesia. Gulf states are redirecting petrodollars to secure investments in minerals used in green technology such as electric cars © Mast Irham/EPA-EFE/ShutterstockZambian officials believe IRH can source technical expertise from IHC’s web of companies to revitalise Mopani.

But one local mining executive says they have “not seen a huge amount of focus” on building good relationships with the community, which is crucial to the success of a project.

Sibanye, for example, had been consulting with local people to hear their concerns.

“I think that’s going to catch them out,” the executive adds.

Underlying community reservations about IRH is a lack of transparency over who is involved in the company, as well as their records and business ties.

When the Mopani deal was finalised, the company revealed its chief executive officer as Ali Alrashdi, who also runs Auric Hub, a gold refinery in the UAE. Sibtein Alibhai, the face of IRH for various stakeholders, is global head of strategy, according to people familiar with the matter.

Alibhai was previously head of Primera Group, an Abu Dhabi-based gold trader, that supplied Auric with gold shipments from the DRC, according to corporate records and the UN.

Last year, Primera was granted a 25-year monopoly by the DRC government for all “artisanal”, or hand-dug, gold supplies.

Under the deal, which the government says will stop illegal mining revenues from funding conflict and entering into neighbouring Rwanda, Primera only pays 0.25 per cent tax versus 6 per cent for other exporters.

The unusual arrangement attracted controversy.

A UN group of experts identified “shortcomings in Primera’s due diligence obligations”, noted criticisms of its “de facto monopoly” and said smuggling continued to thrive.

Primera Group did not respond to a request for comment.

Notably, IRH’s name before incorporation in 2022 was “Auric Hub Holdings”.

IRH, whose website says it has operations or prospects in seven African nations including the DRC, declined to comment on whether it had subsumed Primera Group or any other companies underneath it.

Instead, IRH said in a statement that it believed “sustainable mining can propel economic growth, deliver meaningful impact in communities, and position the UAE as a global leader in resource management”.

For Zambia and other resource-rich nations, whether Gulf investment will be a success will not only depend on whether the technical expertise, community benefits and wider infrastructure investment can be delivered.

It will also hinge on whether the Middle East can achieve its own economic and strategic aims.

One of the biggest questions hanging over the extent of Gulf involvement in mining is the speed at which state agencies can move.

Grand political deals and regional rivalry will accelerate activity, but advisers say that the Gulf nations — particularly Saudi — are hamstrung by bureaucratic wrangling over the strategy, who is in control and which assets to buy.

“The issue in the long run is whether they will have adequate industries from these investments or [if] it becomes just another investment which doesn’t support their aspirations for industrialisation and the diversification of their own economy,” says Kakenenwa Muyangwa, chair of ZCCM-IH, the Zambian entity that sold Mopani.

“There’s a trend — it’s like a tide,” he warns.

“But trends come and go.”

Additional reporting by Joseph Cotterill in London and Ahmed Al Omran in Riyadh

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario