The Businesses That Rescued America From Inflation, Recession, Lost Jobs

From oil drillers to chip makers, businesses responded to soaring prices by boosting supply, which cooled inflation without a recession or high unemployment

By Greg Ip

From left, new cars delivered to a Pittsburgh dealer; Elevation Resources drilling rig in Texas; apartments under construction in Austin; travelers checking baggage at the Southwest Airlines counter in Denver. AP (2), REUTERS, GETTY IMAGES

From left, new cars delivered to a Pittsburgh dealer; Elevation Resources drilling rig in Texas; apartments under construction in Austin; travelers checking baggage at the Southwest Airlines counter in Denver. AP (2), REUTERS, GETTY IMAGESThe U.S. economy surprised nearly everybody last year.

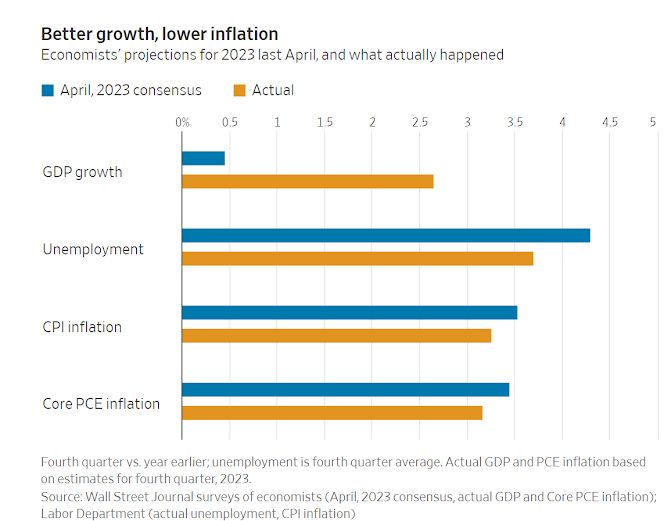

First, inflation fell by more than expected.

One closely watched measure coming next week will likely show it was around 3% at the end of 2023—2 percentage points lower than a year earlier.

Second, the U.S. not only dodged a recession, it grew an impressive 2.6%, according to The Wall Street Journal’s latest survey of economists.

That was far better than the 0.5% they had predicted in April.

The unemployment rate stayed near a half-century low of 3.7% instead of topping 4% as economists projected.

Fast growth and low unemployment don’t normally go hand-in-hand with falling inflation.

The reason they did this time is that since the pandemic, inflation and growth have been driven more by swings in the supply of goods and services than by demand—that is, spending by consumers, business and government.

More demand tends to push growth and prices up.

More supply tends to push growth up, but prices down.

“This cycle is different,” said Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs.

“A natural disaster is a better model than the demand-driven cycles of the 1970s, or other postwar year business cycles.

That’s made it much easier, with supply recovering, to keep output growth on track but nevertheless bring inflation down.”

From 2020 to 2022, businesses couldn’t meet the demand unleashed by an economy reopening after the worst of the pandemic and fueled by government stimulus.

They lacked parts, labor, transport capacity and land. The result: Prices shot up.

Yet businesses don’t sit idle when there is an opportunity to profit from high prices and unmet demand.

So they boosted output by all possible means—raising capital, reorganizing production and boosting capacity.

“We’re going to make hay while the sun shines,” Ric Campo, chief executive of Camden Property Trust, told investors in 2021, when the company was cranking up apartment projects.

The supply side curative has its limits.

High interest rates, better staffing levels and cooler demand have relieved the urgency of adding capacity.

Attacks by Iranian-backed militants on shipping in the Red Sea and a fresh grounding of some Boeing jets are reminders that supply chains are still vulnerable.

Some economists still expect a recession.

Though prices are rising more slowly, many people remain upset over paying so much more for goods and services than they did three years ago.

Yet the remarkable rebound in supply goes a long way to explaining why in the past year prices are rising more slowly, despite brisk demand, or even falling in many industries.

Airlines

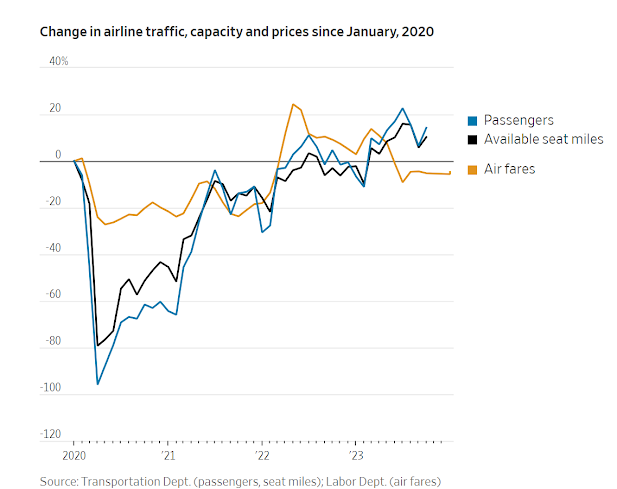

U.S. airlines carried 13% more passengers through the first 10 months of 2023 than a year earlier, yet airfares for the full year were 5% lower, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

This is partly because jet fuel was cheaper, but also because domestic capacity grew faster than passenger loads, resulting in less-full planes.

Nationwide, airlines offered 91% more seat miles last October than in January 2021 and 11% more than before the pandemic, according to the Transportation Dept.

When travel collapsed in 2020, airlines had scrapped routes, mothballed planes and encouraged staff to retire.

As lockdowns ended and vaccination spread, the surge in so-called revenge travel caught airlines unprepared.

The main problem was a shortage of workers.

“We’d always been plane-restrained or gate-restrained.

Coming out of the pandemic, for the first time we were people-restrained,” said Greg Muccio, head of talent acquisition at Southwest Airlines.

Starting in 2022, Southwest held mass recruiting events, often in hotel ballrooms close to its hub airports.

To shorten the lag between interviews and hiring, Southwest sometimes conducted background checks and drug screening at those events.

Last June, Southwest booked Coors Field in Denver, home of the Colorado Rockies, bringing in baggage handling and aircraft-moving equipment for prospective employees to try out.

Of 572 attendees, the airline hired 258.

To prepare for so many new hires, Southwest’s training centers added classes and expanded class size.

As a result, Southwest boosted capacity by about 15% through September 2023 from a year earlier.

It flew a record number of flights on Labor Day weekend with barely a hitch.

The airline had 74,000 employees, as of October, up 19,000 from the end of 2021 and well above its prepandemic level.

The shortage of pilots, who require years of training, was especially serious.

Larger airlines recruited from regional airlines, corporate fleets and in-house training.

Southwest Airlines’ training program, Destination 225, graduated its first class last year.

Major carriers eventually hired more than 12,000 pilots in both 2022 and 2023, more than double the prepandemic pace, according to FAPA.aero, a pilot-advisory firm.

To make the most of the pilots they had, some airlines shunted capacity to busier routes and replaced smaller planes with larger ones.

In December 2022, United Airlines offered 115 departures from Key West, Fla., on regional affiliates flying jets with 70 to 76 seats.

Last month, it had 94 scheduled flights, most of them operated by United on 126-seat Boeing 737s.

That yielded 25% more seats on 18% fewer flights.

Oil

In the oil markets, the supply problem wasn’t a lack of labor or parts.

It was geopolitics.

After Russia invaded Ukraine, Western nations cut off Russian oil imports.

In previous years, U.S. exploration and production companies often responded to higher oil prices by drilling more in shale formations.

This time, oil companies, under pressure to boost shareholder returns, were expected to restrain capital spending and instead give priority to dividends and share buybacks.

Many scrappy, privately held producers decided to crank up output.

Some, like Midland, Texas-based Elevation Resources, did it with their single rig.

The company operates in the Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico, the most active crude field in the U.S.

It takes about six months after a well is drilled to produce oil, so the company didn’t start ramping up production until well into 2022, CEO Steven Pruett said.

A drilling crew working on a pipe connection in Midland, Texas, for Elevation Resources. PHOTO: NICK OXFORD/REUTERSSince the fourth quarter of 2022, the company’s oil-and-gas production grew by about a third to around 10,000 barrels of oil and gas a day, Pruett said, a company record.

Elevation drilled 15 wells last year, up from 12 in 2022.

“We did all we could with that one-rig program,” he said.

U.S. crude oil output hit a monthly record in September.

For the first 10 months of 2023, it averaged 12.9 million barrels a day.

That was about half a million more than the Energy Information Administration had projected for 2023, back in January 2022.

The oil market is global, so U.S. consumers only benefit indirectly from higher production.

Still, that effect is important.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, in cooperation with Russia, has tried to prop up prices by restraining production.

And recent attacks on shipping in the Red Sea have interrupted shipments.

Without stepped-up U.S. shale output, those forces would have pushed oil and gasoline prices higher.

Housing

As interest rates fell in 2020, demand for new housing soared.

When lockdowns ended, many younger people escaped cramped quarters—such as their parents’ house—driving up rents and home prices.

Economists and industry experts warned that the supply of new housing stock was years behind.

Construction had been subdued ever since the 2007-09 recession.

Materials and workers were in short supply.

Land wasn’t available where people wanted to live.

One slice of the industry, multifamily developers, defied predictions, ramping up projects to benefit from soaring rents.

“People wanted a piece of that,” said Jesse McConnico of John Burns Research and Consulting, a real estate adviser.

In the first months of 2021, the leasing offices at Camden, which operates across the Sunbelt, were shaken from the doldrums.

“All of sudden in March, April, our offices were jammed with people, 10 deep,” Campo, the chief executive, said.

By the fourth quarter that year, new leases on Camden’s 58,300 units were 16.5% higher than a year earlier.

With interest rates low and capital markets buoyant, Camden issued $1.3 billion in stock in 2020 and 2021 to expand its new project pipeline.

Like most builders, Camden had to cope with shortages of material, equipment and labor.

“You have to work hard to get people to come to your site,” Campo said, such as by paying promptly.

“We have an old adage: fast pay, fast friends.”

To keep workers coming in during the 2022 World Cup, the company put TVs on construction sites and served snacks and lunch.

From 2020 to 2022, Camden broke ground on seven projects totaling more than 2,000 houses and apartments.

A 420-unit apartment building in Durham, N.C., opened six months ahead of schedule in 2023.

Camden expanded into single-family rentals.

Last fall, it started leasing 189 houses in Houston.

Camden’s projects were part of a record 439,000 units completed last year, according to RealPage.

McConnico estimates another 600,000 to 650,000 will be completed this year.

Not surprisingly, rents on new leases have stopped rising.

At Camden, new lease rates were down 3.3% in the fourth quarter through late October compared with the fourth quarter of 2022, Campo said.

At new projects, there are offers of a month’s free rent.

Because of higher interest rates, he said unbuilt units are “on hold, until we have some clarity about the world.”

Even with developers pulling back, the flow of units begun in past years will continue to hit the market, easing the pressure on rents.

Measures of housing inflation remain high, but downward pressure should build this year.

Chips

A shortage of semiconductors during the pandemic had an unexpected and significant impact, pushing up prices of the many products that use chips, particularly cars.

The chip industry’s ability to boost output helped boost supply and cap prices of products that use them.

New vehicles contain more than 1,000 chips—ones simpler and much cheaper than chips in high-end applications such as artificial intelligence.

At the start of the pandemic, car companies, expecting a prolonged sales drought, canceled their chip orders.

Suppliers reallocated that capacity to other products such as personal computers, which enjoyed high demand in a new remote-work-and-schooling era.

When car companies finally placed new orders, they faced long waits.

With fewer cars for sale, prices shot up along with profits.

A near-empty lot at a Ford Motor Co. dealership in Colma, Calif., during a period of dwindling inventory in 2021. PHOTO: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG NEWS

A near-empty lot at a Ford Motor Co. dealership in Colma, Calif., during a period of dwindling inventory in 2021. PHOTO: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG NEWSThe semiconductor industry is highly cyclical.

Facing such strong demand, chip makers had to decide whether to add to capacity.

The upside: lots of new sales.

The downside was a possible collapse in demand, rendering the capacity unnecessary.

Most decided that “the lost potential profit of not having the capacity available is bigger than the downside if you get it wrong,” said Stacy Rasgon, a semiconductor analyst at Bernstein.

In October 2021, Vivek Jain became head of manufacturing and supply chain operations at Analog Devices, which makes roughly 75,000 types of chips for industrial, automotive and electronics products across a hybrid network of in-house and outsourced factories.

At his first board meeting that December, he laid out a road map to boost capacity.

One quick way was to expand production at a fabrication plant in Camas, Washington, from five to seven days a week.

Given the tight labor market, Jain said, “we thought it would be quite hard.”

But employees welcomed the option of working 12-hour days three or four days a week, he said, instead of the usual five-day workweek.

The company boosted capacity at fabrication plants in Beaverton, Ore., and Limerick, Ireland, by installing additional chip-making tools.

Some tool makers who were themselves short of chips agreed with Analog to give priority to each other’s orders.

“It was a good exchange,” Jain said.

He estimates chip capacity is 40% higher than before the pandemic.

For automakers, chip shortages are largely over.

As a result, inventories are rising, and prices in December were lower than a year earlier, according to Cox Automotive.

The economy isn’t out of the woods.

Inflation, while much lower than a year ago, is still higher than in 2019, and wages are still growing faster than is compatible with the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

Whether inflation falls further—and recession avoided—will be mostly a question of demand.

Supply has done its part.

Benoît Morenne and Alison Sider contributed to this article.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario