How Work From Home Has Reshaped What Americans Buy

The shift back toward spending on services has largely ended, which leaves Americans devoting a bigger share of their spending to goods than before pandemic

By Justin Lahart and Jinjoo Lee

Analysis shows consumers are buying goods as a substitution of sorts for the services they used to buy—like purchasing a bicycle instead of spending money on a spin class near work. PHOTO: TERRA FONDRIEST/BLOOMBERG NEWS

Analysis shows consumers are buying goods as a substitution of sorts for the services they used to buy—like purchasing a bicycle instead of spending money on a spin class near work. PHOTO: TERRA FONDRIEST/BLOOMBERG NEWSAmericans are still spending more of their money on stuff than they did before the pandemic.

There is little reason to think that is about to stop.

Early in the pandemic, unable to spend on things such as traveling and dining out, and with their finances buoyed by government relief, people bought goods with abandon.

This played a role in the supply-chain snarls, the hefty price increases that beset the economy, and in retailers’ scramble to secure as much inventory as possible.

As the economy gradually reopened there was a reversal that left many stores burdened with more than they needed.

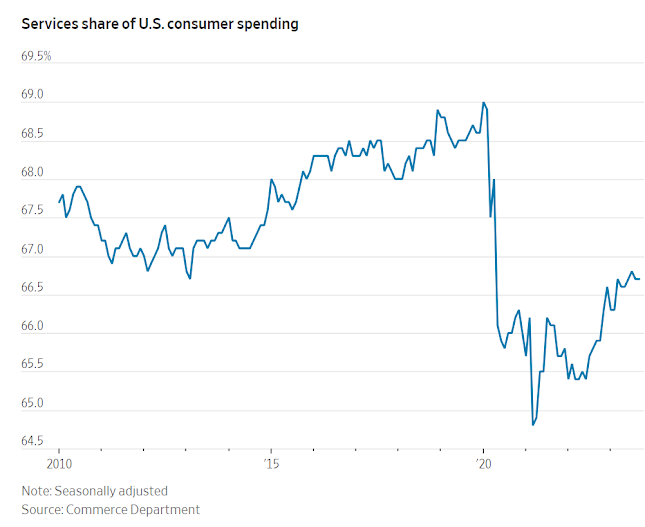

Now, the rebound in services’ share of spending seems to have ended, and retailers’ inventory problems largely have been wrung out.

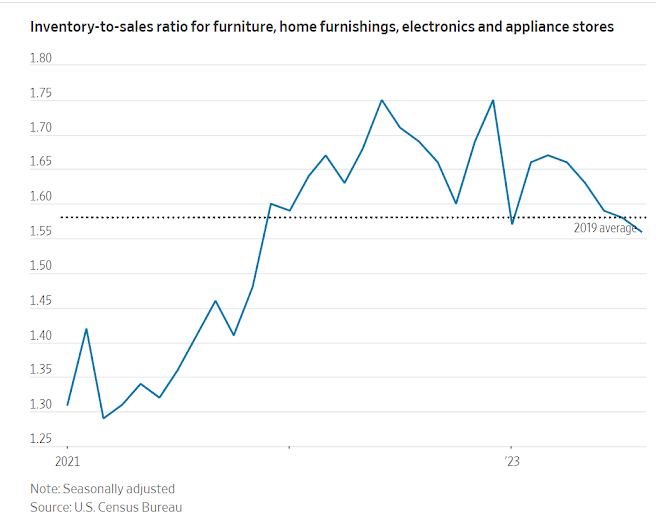

Those selling furniture, electronics and appliances, for example, saw their inventory swell to as much as 1.75 times sales in December 2022, according to data from the Census Bureau.

As of August, that ratio shrank back to 1.56, which is pretty much in line with prepandemic levels.

U.S. consumers are still devoting a lot of spending toward goods—a reshaping of the economy that, in addition to any far-reaching consequences it might have, suggests retailers’ 2023 holiday-season sales will be much higher than they might have imagined in 2019.

Figures from the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis show that U.S. consumers devoted a seasonally adjusted 33.3% of their spending to goods in September compared with an average of 31.4% in 2019.

With goods prices moderating lately while services prices continue to climb, inflation doesn’t play much of a role in that.

Indeed, adjusted for inflation spending on goods was 20.4% higher in September than the 2019 average, while services spending was just 7.6% higher.

To some degree Americans’ new penchant for goods purchases might reflect a rethinking of priorities since the pandemic—an increase in, call it, homebodyness that led some people to prefer the dining room table over the restaurant, and the living room couch over the theater seat.

But the most obvious and lasting change is that a lot of people are working home a lot more than they did before the pandemic.

A survey conducted by the Census Bureau during the latter half of last month showed that, among respondents who answered the question, 29% of U.S. households included someone who had teleworked at least once over the past seven days.

That was almost exactly the same share as a year earlier—an indication of the staying power of the work-from-home revolution the pandemic set off.

People who work from home more don’t avail themselves of some services as much as they used to.

They don’t spend as much money taking public transportation to work, for example, or at downtown lunch spots and after-work watering holes.

If they used to have a gym membership near their office, maybe now they don’t.

They buy stuff instead.

But a Goldman Sachs analysis shows that the stuff they buy is often a sort of substitution for the services they used to buy.

If they aren’t buying a monthly bus pass, maybe they buy an office chair.

If they aren’t spending money on a spin class near work, maybe they buy a bicycle.

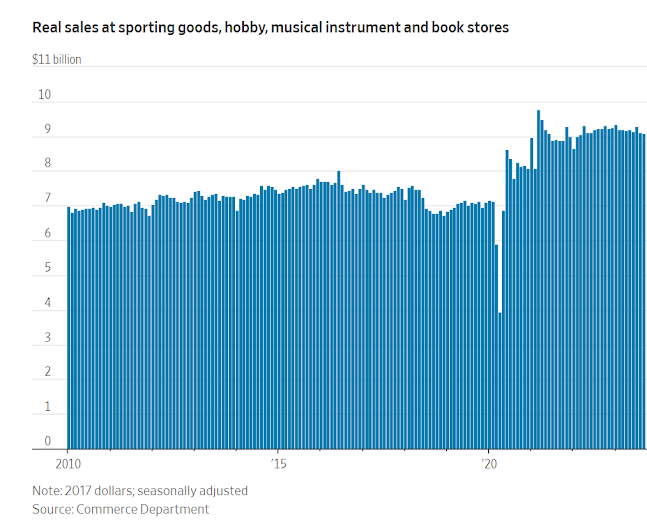

Commerce Department figures reveal this pattern.

For example, inflation-adjusted, or real, sales at sporting goods, hobby, musical instrument and book stores went pretty much nowhere in the decade before the pandemic, in part because of the steady encroachment of online competitors.

But in September, their real sales were 29% higher than the 2019 average.

Conversely, in areas where work-from-home effects are less pronounced, or nonexistent, spending patterns look more like they did before the pandemic, Goldman’s economists found.

Healthcare spending has pretty much recovered to its old trend, for example.

Spending on clothing and footwear has fallen most of the way back down.

Retailers have noticed.

At a conference in September, Home Depot Chief Executive Edward Decker said the home-improvement sector’s share of personal-consumption expenditures is moderating compared with peak pandemic levels, but that he is still bullish on where that share lands.

“Even if you’re back to working three days a week, most people are one, two, even three days or more a week working from home.

So you’re using the house more,” he said.

Even after the pandemic withdrawal, Home Depot’s U.S. division and Lowe’s are set to make 38% and 21% more revenue this fiscal year than they did in 2019, respectively, estimate Wall Street analysts polled by Visible Alpha.

Both Williams-Sonoma, which owns Pottery Barn, and online furniture seller Wayfair are expected to make about a third more in revenue this fiscal year than they did prepandemic.

Dick’s Sporting Goods’ revenue for the current fiscal year is on track to be 46% higher than 2019 levels if its third- and fourth-quarter results line up with Wall Street analyst estimates.

The postpandemic comedown for retailers—at least some of them—might not be so painful after all.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario