Egypt’s Singular Role in Gaza

For Cairo, there are risks and opportunities involved in managing whatever comes next.

By: Kamran Bokhari

As the international community struggles to figure out what to do with Gaza after the war, Egypt is poised to play its biggest role there in more than 50 years.

Whether it likes it or not, it is the focal point of efforts that involve the United States, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Turkey, a responsibility that will present as many opportunities as risks.

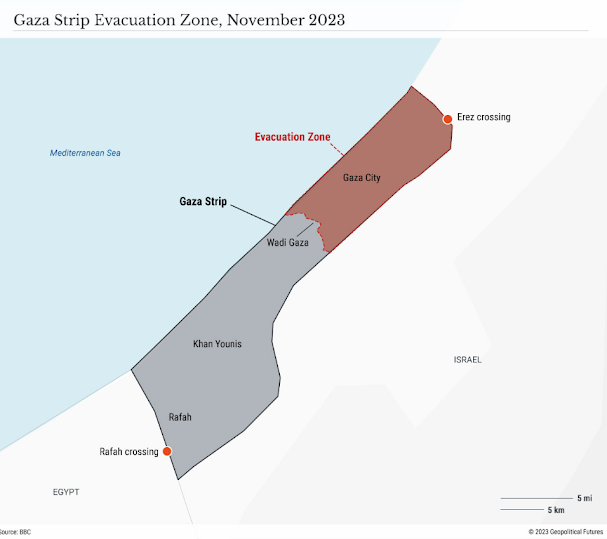

On Nov. 8, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the Gaza Strip cannot continue to be run by Hamas, but that neither could it be reoccupied by Israel beyond a transition period after the end of the military offensive.

He also mentioned that U.S.-led international efforts are meant to ensure that there is no displacement of the Palestinian population and to reinstate the “unity of governance” between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

This is a difficult road map to follow.

The key challenge will be to minimize the length of Israel’s occupation and administration of Gaza.

Already there is mounting international and domestic pressure on the Biden administration to broker a cease-fire.

That so many Palestinians have been killed – more than 10,000 as of Nov. 7 – has shifted the narrative on the war from condemnation of Hamas to criticism of the Israeli counteroffensive.

Implicit in this pressure is the debate over the broader occupation of the Palestinian Territories, the rise of Hamas and the immorality of terrorism.

Under these circumstances, it is in neither America’s nor Israel’s interest to see Gaza reoccupied.

After all, Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza in 2005, when the territory was still under the control of the Palestinian Authority, and when Israel Defense Forces had largely stopped Hamas’ suicide bombing campaigns.

However, Hamas’ legislative victory the following year created a situation in which Hamas would rule Gaza while its rival, Fatah, would govern the West Bank.

Toppling the Hamas government in Gaza would upend this 16-year arrangement, which allowed Egypt to step back from the conflict – other than to manage the flow of goods and people in and out of the Gaza Strip.

Egypt’s position on Gaza is defined by two different periods.

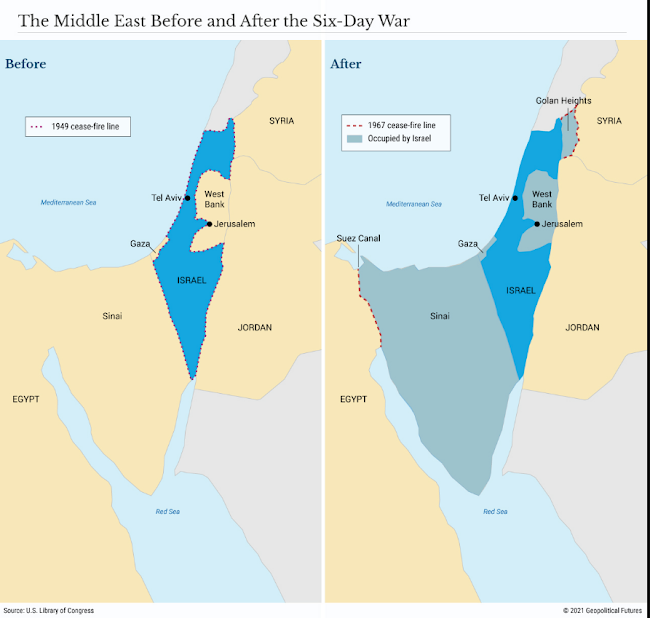

The first began with the war in 1948, when Egypt, Syria and Jordan sought to seize control of what used to be British-ruled Palestine, large parts of which had become the state of Israel that same year.

The Arabs lost the war, of course, but Egypt gained control of the Gaza Strip.

After the 1952 coup – which essentially established the military-dominated regime that rules Egypt to this day – Cairo continued to advance an agenda of defeating Israel and liberating Palestine (if not necessarily as an independent state).

This would lead Egypt, Syria and Jordan to fight and lose the 1967 war, in which Cairo lost control of Gaza as well as the Sinai Peninsula – a much larger and more strategic piece of land.

Thus, the final war between Egypt and Israel in 1973 was no longer about Palestine so much as it was about retrieving the Sinai, which the Egyptians eventually reclaimed per the 1978 peace treaty with Israel.

In other words, a new normal was established in which Cairo no longer considered Palestine a strategic issue.

And when, a decade or so later in this second era, the Palestine Liberation Organization decided to give up armed struggle to pursue its cause diplomatically, the Palestinian issue became, from Cairo’s point of view, an Israeli concern.

Even so, the rise of Hamas was a major problem for Cairo because Hamas is an armed offshoot of the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s largest opposition movement.

Yet Egypt took comfort in the fact that between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, Hamas would be contained.

It wasn’t, and the group’s takeover of Gaza forced Cairo to take a more active role in managing the territory. The new Egyptian strategy was two-fold: coordinate with Israel on a blockade of Gaza and establish a working relationship with Hamas so that Cairo can serve as a mediator with Israel – which it did during the wars in 2008, 2012, 2014 and 2021.

This arrangement was tested in the wake of the Arab Spring uprising, when the Muslim Brotherhood briefly came to power in 2012.

Though the group took a pragmatic approach to Gaza, the Egyptian establishment wasn’t taking any chances; it was too concerned about the prospect of a Muslim Brotherhood government in Cairo, Islamist militancy in the Sinai and a Hamas-led regime in Gaza.

To the establishment, this was a threat not just to Egypt’s stability but to the peace treaty with Israel.

Thus came the coup in 2013 that removed the Muslim Brotherhood from power and installed military chief Abdel Fattah el-Sissi as the country’s president.

While suppressing the Muslim Brotherhood at home, the new government continued its limited, pragmatic engagement with Hamas as a way to insulate itself from the brand of Islamism gaining ground next door.

Meanwhile, el-Sissi had other major issues to deal with, including a floundering economy kept afloat by billions of dollars of assistance from the Gulf Arab states.

Regime stability was a stated priority of el-Sissi’s when he confirmed he would seek a third term – an announcement he made just four days before the Oct. 7 attacks radically altered Egypt’s strategic environment.

Cairo will now have to do much of the heavy lifting. It’s unclear how the government will deal with the messy process of regime change in Gaza while maintaining regime stability at home, especially since the Egyptian public is highly sensitive to the suffering of the Palestinians in Gaza.

It is so sensitive, in fact, that the government made the unusual move of allowing pro-Palestinian demonstrations to take place in Cairo on Oct. 20, during which protesters criticized Egypt’s handling of the economy.

However, Hamas’ dismantlement by Israel isn’t without opportunities for Cairo. Egypt is eager to weaken the Islamist movement, as are its benefactors in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, which oppose Islamism on its merits but also want to deny Iran the ability to exploit the Gaza issue.

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are therefore likely willing to invest in the efforts to re-establish a post-Hamas order in Gaza.

No other country than Egypt would benefit as much from the arrangement.

(This is especially important as Saudi Arabia recently said it would stop giving out money to countries such as Egypt with no strings attached.)

But it’s still a tall order.

Once the dust settles, Hamas will be weakened but probably not eliminated.

The Palestinian Authority in the West Bank will have to restore its writ over Gaza, but the group is famously corrupt and approaching a chaotic transition.

Israel can bring down the Hamas regime in Gaza, but Egypt will have to take the lead in establishing a new order there, and fast in order to avoid the pandemonium of an Israeli reoccupation becoming longer than intended.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario