Preparing for a Changing Climate

Copenhagen's Far-Reaching Transformation into a "Sponge City"

By Jan Petter and Charlotte de la Fuente (Photos) in Copenhagen

Karens Minde park has been revamped as catchment area for water in the event of future extreme weather events. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

As the climate warms, Copenhagen is likely to see more torrential rain storms like the one that inundated the city in 2011.

Since then, the Danish capital has taken action, redesigning parks and streets to quickly drain away vast amounts of water.

It’s shortly after 1 p.m. on a gray, Wednesday afternoon as Ditte Juul Sørensen, standing in a park in southern Copenhagen, talks about how she intends to flood the dog park should it become necessary.

The green area used to consist merely of a sodden meadow, a decrepit playground and a couple of dirt paths.

But over the last seven years, the 46-year-old landscape architect has completely transformed it.

Today, it marks the end of an invisible river that winds its way through Copenhagen, designed to save the city in the event of torrential rainfall.

"The meadow will collect the water," says Sørensen, "and this artificially created riverbed will lead it onward."

She points to a red-and-yellow paved pathway leading back to the petting zoo.

In total, the invisible catchment area can hold 15,000 cubic meters of water, roughly the equivalent of 83,000 bathtubs filled to the brim.

The park is one of the endpoints of an extensive network of above-ground and underground canals, green spaces, specially adapted roads and catchment ponds.

The Skybrudsplan, or Cloudburst Management Plan, cost 1.8 billion euros and it is designed to protect the city from episodes of severe rainfall for the next 100 years.

Ditte Juul Sørensen and Jan Rasmussen, two of the planners behind the Skybrudsplan Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

Ditte Juul Sørensen and Jan Rasmussen, two of the planners behind the Skybrudsplan Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL Locals in Karens Minde park: "We all have a shared responsibility." Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

Locals in Karens Minde park: "We all have a shared responsibility." Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGELExtreme weather events struck all over Europe this summer, and they are likely to become even more common in the future as global warming advances.

Some parts of the continent had to face heatwaves, fires and drought, others were struck by unpredictable storms.

The Danish capital, for its part, is among those places threatened by torrential rains and flooding.

In July, Denmark saw twice as much rain as normal – more than ever seen for the month in the last 149 years.

For many, it was reminiscent of 2011, the year the city went through something of a collective trauma, a moment of chaos that can be seen in hindsight as a wake-up call.

On the evening of July 2 that year, two-months worth of rain poured out of the sky within just a few hours.

Tens of thousands of people found themselves without power, the university hospital’s trauma center had to be evacuated, parts of the historic citadel even collapsed and broken district heating pipes resulted in a number of scalding victims.

The police department’s telephone system was out of order for three days, while the World Health Organization had to close down its European headquarters and the Tivoli Gardens amusement park was evacuated.

Afterwards, dead rats floated through the streets.

According to one study, 22 percent of workers surveyed fell ill during the weeks of cleanup that followed.

One man even died of an infection.

Prisoners had to be fed with McDonald’s food because the kitchens were destroyed.

In Copenhagen alone, the damage was estimated at 800 million euros.

The Danish capital spent years on the project of cleaning up the water in the city's harbor. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

The Danish capital spent years on the project of cleaning up the water in the city's harbor. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL The Copenhagen harbor is now safe for swimming thanks to that effort. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

The Copenhagen harbor is now safe for swimming thanks to that effort. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGELThe city reacted with resolve.

Not even a year passed before Copenhagen passed its first Skybrudsplan.

Since then, the concept has been further developed each year, with construction planned to continue until at least 2035.

Jan Rasmussen, a 61-year-old who has worked for the city as an engineer since 1990, is one of the authors of the plan.

He has spent his entire life focusing on water, with the first 20 years of his career dedicated to making it cleaner.

Together with water utility staff, he ensured that the once murky waters of the harbor ultimately became clean enough for swimming.

"I didn’t even think myself that we’d be able to do it," Rasmussen says.

Today, he's fighting to keep it that way.

When too much water falls from the sky in a short amount of time, even the best drainage systems are overwhelmed.

Sewage treatment plants and waste pipes are flooded, as are basements.

In a densely populated city, there are very few natural pathways for the water to escape, and so it follows the course of least resistance, forcing its way through the city in a muddy, filthy current.

"You have to slow it down and guide it so it doesn’t cause any damage," says Rasmussen.

Following the 2011 storm, he joined other experts in producing a map of rainwater flows.

They documented rises and depressions while also including sealed surfaces, roofs and green areas.

They used the map to highlight the corridors the water would take and where it would run up against obstacles.

The horses in the petting zoo at Karens Minde can stay, despite the changes being made. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

The horses in the petting zoo at Karens Minde can stay, despite the changes being made. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGELUltimately, the city was faced with three choices.

The first was to do nothing at all.

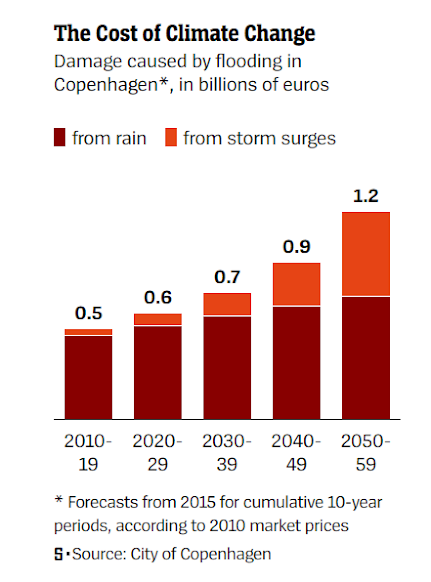

On the basis of the IPCC climate report, Rasmussen and his team calculated the costs of inaction to be more than 2 billion euros in the next 100 years – more of a thought experiment than a real option.

The second choice was to follow the classic playbook of installing more drainpipes and cisterns.

The third option was more novel and rather unusual, but it looked to be by far the most efficient course of action.

It involved developing a model for the city made up of a mixture of an underground network of facilities for draining and collecting water, parks to serve as backup catchment capacity and streets able to act as rivers in periods of intense rain.

"We are building this because it makes more sense.

The Skybrudsplan can do more and costs less," Rasmussen believes.

The vision calls for Copenhagen to become a city that can absorb water and release it slowly despite urban density.

"We Are Pioneers"

The "sponge city" concept is not unique to Denmark, and rapidly growing Chinese metropolises, in particular, have adopted elements of the idea.

But nowhere has it been as sweepingly deployed as in Copenhagen.

Fully 350 individual projects are part of the plan.

"We really didn’t have any role models we could follow in the world," says Rasmussen.

Only a small number of the projects have been financed by taxpayer money, with most funding being collected by the water utility through a levy on households and companies.

Rasmussen believes that such a financing model, which is directly linked to consumption, is the easiest and fairest solution.

For a four-person household, water fees rose by around 120 euros ($128) per year.

"If you consider the risks posed by climate change, such costs are justifiable," the engineer says.

Following the 2011 flooding, many insurance companies threatened to cancel policies and a number of businesses began talking about leaving the city.

"Even a UN organization told us that Copenhagen was a risk as a location," Rasmussen says.

The engineer believes he will be working on implementing the Skybrudsplan until his retirement a few years from now.

His maps have now grown to include larger arterials that can handle significant quantities of water, parking lots where it can slowly drain away and side streets to take care of everything that streams down from the rooftops.

"Of Course There Was Disagreement"

Ditte Juul Sørensen, the project manager and landscape architect – one of 11 that Copenhagen hired for the Skybrudsplan – leads the way to a strip of green.

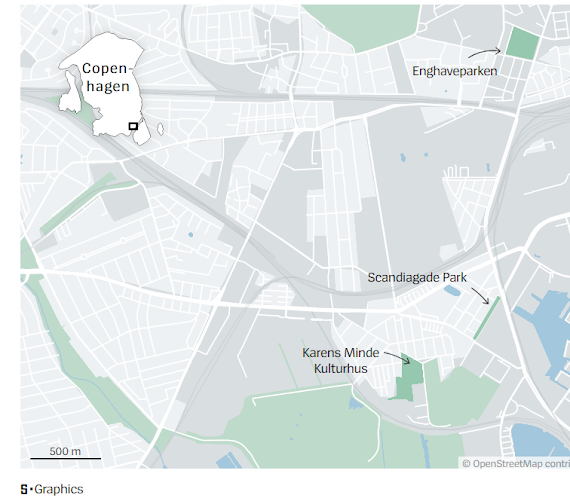

The site on Scandiagade Street is so small that it isn’t even included on Google Maps as a park.

Seven concrete basins have been installed here, but they are hardly visible at first glance.

There is a butterfly garden, vegetable beds, benches and even a hammock.

A brightly painted walkway leads from one basin to the next.

It is a perfect example of the city wanting to use the Skybrudsplan to improve the quality of life for city residents.

"The project team asked the people here what they wanted," says Sørensen – and the consensus was more color and more nature.

So the vacant strip of land was transformed into a city garden.

Only the last basin, at the very end, has a bit of rainwater in it at the moment, and the ground is damp.

The road running along the green strip was adjusted slightly so that water can run off into the basins during heavy rainfall.

From the basins, the water can either percolate into the ground or be guided through underground channels to the harbor.

Locals use the green strip as a park, with its true purpose largely concealed. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

Locals use the green strip as a park, with its true purpose largely concealed. Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL Walkways leading between the catchment basins on Scandiagade Street Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

Walkways leading between the catchment basins on Scandiagade Street Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL Enghavepark neighbor Rasmus Lütken (middle) with members of his pétanque club: "It is absolutely the right decision for the city to do this." Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL

Enghavepark neighbor Rasmus Lütken (middle) with members of his pétanque club: "It is absolutely the right decision for the city to do this." Foto: Charlotte de la Fuente / DER SPIEGEL"Public participation has ensured that the majority are supportive of the project," says Sørensen.

And that’s not the only reason they sought input from locals: The gardens, it is hoped, will encourage residents to maintain the property and ensure that the basins don’t become filled with trash.

Still, one wonders how it has been possible for Copenhagen to revamp parks and roads for flood protection with relatively little protest when a city like Berlin can’t even build 500 meters of bike paths without a major uprising.

"Of course, there was disagreement," admits Sørensen.

And discussions didn’t always go as well as they did for the Scandiagade Street project.

In the neighborhood surrounding the Karens Minde Kulturhus cultural center, residents were initially less than ecstatic about plans to transform their park into a catchment basin for the rest of the city.

She says she held regular meetings with neighbors for three years, telling them that the lindens and poplars, which are under protection, wouldn’t be touched.

In the end, locals were able to choose the paving stones and benches for the park, but the plan itself was never up for debate.

"We all have a shared responsibility," says Sørensen.

And some of the projects are so inconspicuous that nobody notices them anyway.

Further north in Enghavepark, for example, a new space for inline-skate hockey has been installed, surrounded by a low, concrete wall.

Members of the pétanque club next door use the wall for sitting or to set down their wineglasses.

They are surprised to learn what the wall’s true function is, saying they never would have guessed that the space is intended as a basin for collecting rainwater.

Everyone in the group still has clear memories of the 2011 catastrophe – of mud-covered wedding dresses and destroyed furniture.

"It is absolutely the right decision for the city to do this," says Rasmus Lütken, an artist and architect who is part of the pétanque group.

For him, he says, the biggest question is whether the plan goes far enough or whether more might be necessary.

"Plus,” he says with a grin, "it looks pretty good."

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario