China, India and the Path to Escalation

Beijing’s clashes with New Delhi are part of the Chinese strategy to extract concessions from Washington.

By: Kamran Bokhari

There is growing international concern about a potential conflict between China and India over their disputed border in the Himalayas.

However, the possibility of a war between the two neighbors has to be understood in the context of the increasing pressure Beijing is coming under both domestically with a faltering economy and on the foreign policy front with U.S.-led containment efforts.

These circumstances could lead Beijing to become more assertive with India in an effort to extract concessions from Washington, a key partner for New Delhi.

This week, U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo visited China for talks requested by her Chinese counterpart as part of Beijing’s efforts to repair relations and slow its economic downturn.

But China’s recent engagements with India have been less placating.

According to a Reuters report, Chinese President Xi Jinping is planning to skip the G-20 summit set to take place in New Delhi on Sept. 9-10 and will send Premier Li Qiang in his place.

Xi’s absence would come just weeks after he held talks with his Indian counterpart on the sidelines of the BRICS summit in South Africa in August.

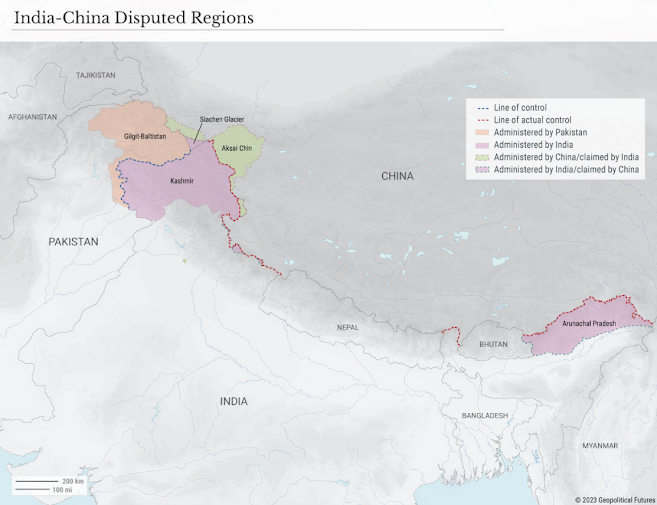

Meanwhile, on Wednesday, the Chinese government released an official map showing India’s northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh and northwestern Aksai Chin region as Chinese territory, drawing strong criticism from the Indian government.

Despite these signs of hostility, over the past few weeks senior commanders from China’s People’s Liberation Army held a series of talks with two- and three-star Indian generals to de-escalate tensions in the western Ladakh sector along the Line of Actual Control, which separates Chinese- and Indian-held territories.

The flurry of meetings at the operational commander level suggested that the two sides were trying to hammer out a deal to return forces to the positions they held prior to Chinese incursions in 2020 that led to violent clashes.

The timing of the talks, ahead of the Xi-Modi meeting in Johannesburg, suggested that a significant deal could have been in the works.

But conflicting official accounts of what was discussed indicate that a resolution will likely not be in the offing for the foreseeable future.

The difficulty in agreeing to a resolution is a result of the fact that China and India have conflicting interests.

China is increasingly at odds with the United States, while India is emerging as a close partner of Washington.

In many ways, India is strategically sandwiched between the two counties.

For Beijing, India is a pressure point that it can use to try to gain leverage in talks with Washington.

It is, after all, the only place where China has some ability to use military power to further its strategic imperatives.

Many believe that China’s military is focused on Taiwan, a perception Beijing certainly feeds into by conducting military exercises in the waters around the self-ruled island.

But the Chinese know well that their military has little combat experience, certainly none in the maritime space, meaning it would be no match for the force structure that the U.S. and its allies have put in place in the Western Pacific.

The PLA does have combat experience against India, with which it fought a war more than half a century ago.

But 1962 was a very different time.

India was a much weaker country than it is now and far more focused on its regional rival Pakistan, which it had fought in 1948 and would fight again.

This was also the height of the Cold War, and Washington was focused on containing the Soviet Union and bogged down in Vietnam.

Neither the Indians nor the Chinese were nuclear powers yet.

The Chinese were thus able to seize control of a chunk of territory in the Kashmir region and in northeastern India.

In the decades that followed, Chinese and Indian forces engaged only in minor clashes (in 1975 and again in 1986-87) in Arunachal Pradesh around the time India was absorbing the disputed area.

Apart from these incidents, the two neighbors remained largely conflict free.

In the 1990s and 2000s, they concluded several agreements to manage their territorial disputes until a permanent settlement could be reached.

It wasn’t until a decade ago that trouble erupted again when Chinese forces began making limited incursions at multiple points on the Indian side of their long border.

Since then, there have been five noteworthy cases of Chinese troops crossing the Line of Actual Control – in 2013, 2014, 2017, 2020 and most recently last December.

None of these incidents, however, involved the exchange of live fire.

Even the 2020 incident, which resulted in several fatalities on both sides, involved hand-to-hand combat with clubs and rocks.

Considering the recent tensions and the firepower that both countries have deployed to their border over the past three years, an outbreak of armed hostilities is quite possible.

However, the Chinese are unlikely to gain territory from such an exchange, given the difficult terrain in the Himalayas.

They also know that the Indians will have close U.S. military and intelligence support in case of a conflict.

Furthermore, India has far more combat experience than China because of the wars it fought with Pakistan.

Thus, the Chinese leadership understands that any conflict with India could have enormous costs, including for its economy, which is already struggling.

The fallout from the war in Ukraine that Russian President Vladimir Putin is dealing with right now is not lost on Xi.

The Chinese will therefore likely tread carefully to find a sweet spot between strategically poking India and avoiding a major eruption.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario