Remember when banks were small?

Those old enough to have a bank account in the 1970s should.

Back then, most people did their banking with a

locally owned institution, often the First National Bank of (Your Town).

These were fully independent banks, not branches of bigger ones.

You could walk in and see the bank president sitting at a big desk.

Even major cities had neighborhood banks, serving the people who lived nearby.

That’s just

the way it was.

Large banks existed mainly in big skyscrapers downtown which most people had no reason to visit, serving big businesses while small banks served small businesses and the masses.

If you needed a loan, you would put on your

best clothes and go ask for one, often speaking to someone you knew from church

and school functions.

Those small banks, while not totally gone, are no longer normal.

The system that replaced them is less personal but more efficient and convenient.

It has enabled enormous economic growth.

Yet I can’t help feeling we lost something important along the way.

My current bank doesn’t understand—or even want to understand the unique aspects of my business.

It

wants to plug me into a cookie-cutter financial model, which dictates new terms

for my line of credit.

Seriously?

I don’t blame them.

They need sterile, standardized models to be efficient.

My current “banker” whom I have never met has no authority to do anything but follow his models.

Reasonable caution on their part but I’m sure this is happening to small businesses all over the country.

Money costs more and banks want more collateral.

But it is forcing me to change

my own business model.

Life was simply easier with local bankers.

I followed one banker to four different banks over 15 years before he moved too far away.

He knew my business as well as I did.

But that was a long time ago in what seems a galaxy

far, far away.

That’s why recent banking events give me disturbing thoughts.

As I

try to analyze where this is going, I see a plausible, and indeed probable

outcome: an even more

concentrated banking industry with less personal banking and even more models.

That’s not great, for a variety of reasons we will discuss today, but even worse is what will happen on the way there.

We could be heading toward

a truly unthinkable series of crises.

To understand why, we need to put several pieces together.

Something Odd

We’ll begin by noting something odd at Silicon Valley Bank: At the

time it failed, some 96% of SVB’s deposits were in excess of the FDIC limit

($250,000 in most cases) and therefore uninsured.

More accurately, they would

have been uninsured except that the FDIC, in consultation with the Federal

Reserve Board and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, invoked a “systemic risk”

clause to extend unlimited coverage to all SVB deposits.

This decision wasn’t cost-free.

Last week the FDIC announced it had, after liquidating SVB’s assets, paid out an additional $20 billion to make depositors whole.

This was charged to the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund, which is funded by assessments on all banks and must now be replenished.

Also keep in mind, the FDIC is backstopped by the US Treasury if its own funds are insufficient.

“Taxpayers” didn’t pay anything this time but are potentially at

risk.

That makes it harder to deny SVB depositors received a “bailout.”

I know it’s a loaded word, but facts are facts.

As I understand it today, the FDIC essentially unloaded SVB’s easily tradeable assets, sold the rest to another bank, and still had to draw from its own reserves to make good on the expanded deposit insurance guarantee.

Those who received the benefit had been clearly warned not to expect any such thing, yet they got it anyway.

“Bailout” seems to fit.

SVB

wasn’t systemic until it was.

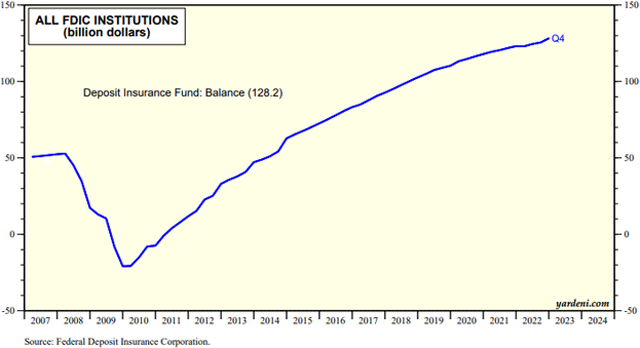

(That $20 billion isn’t spare change, either.

The FDIC’s reserves were $128.2 billion as of last year-end.

SVB alone consumed over 15% of this balance.

A few more such incidents—or even a single large one—could easily deplete this fund.

The FDIC is going to levy a special assessment on other banks to replenish their funds.

Who pays?

The banks?

No, ultimately their customers.

They must keep shareholders happy, just like the consumer products

makers who (blaming inflation and the Fed), raise prices to meet forecasts.

Source: Yardeni

QuickTakes

There’s no obvious reason why these large and presumably sophisticated SVB customers would keep such large amounts of uninsured cash in bank accounts.

A bank account is a loan to the bank.

FDIC assumes the credit risk for balances below the well-known limits.

Above that, any losses are on the depositor.

Moreover, many alternatives are available—sweep programs and such.

SVB itself had one, though few customers seem to have used it.

Why?

I simply can’t believe the CFOs of large companies like Roku—which had almost $500 million of uninsured cash at SVB—did this unwittingly.

All I can imagine is SVB offered some other benefit they thought justified the higher risk and lower yield.

What that benefit was, I don’t know.

Giant Assumptions

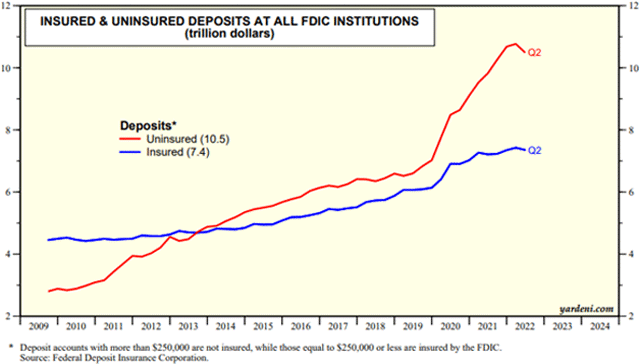

And whatever is going on here, it’s clearly not just SVB.

Here again is a chart from Ed Yardeni I showed two weeks ago.

Observe not just the

amounts, but how uninsured deposit growth accelerated in 2020 while insured

deposit growth stayed close to its trend.

Source: Yardeni

QuickTakes

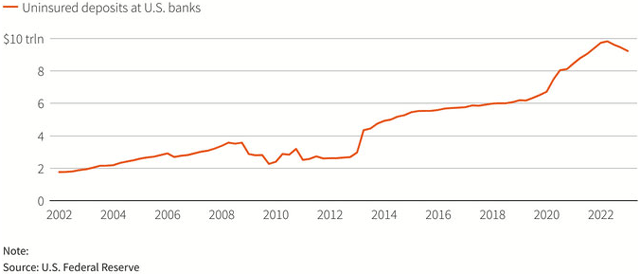

Here’s a longer-term chart of the uninsured deposits.

Source: Reuters

For whatever reasons, large depositors feel increasingly confident with the risk of holding uninsured balances.

Maybe they think the banks won’t fail.

Maybe they feel sure the FDIC will save them even if the bank does fail—which was a winning bet in the SVB case.

But these are giant assumptions

which affect both depositors and banks.

My friend Woody Brock had a brilliant analysis of the banking situation (which he kindly allowed me to share with Over My Shoulder members here).

He makes this important point about “moral hazard:”

“A moral hazard occurs when the provision of insurance changes the incentives and thus the likely behavior of those insured.

For example, if I can obtain $750,000 insurance against my house burning down, when I (unlike the insurer) know that the true cost of rebuilding is $500,000, then I have an incentive to burn the house down to obtain both a new house and a cash bonus of $250,000.

This incentive in turn increases the probability of a house fire because I am now motivated to burn down my house.

The insurance company

understands this possibility which is why it will not insure a house at a value

higher than

its market value…

“In the case of banking,

what insurer in his right mind would insure the owners of a bank against

bankruptcy when (i) the true risks involved cannot be measured, and when (ii)

the risk of moral hazards are ever present – especially if bank managers know

that depositors will never lose money and as a result are emboldened to take

risks they should not have taken.”

To use Woody’s metaphor, we are now in a situation where many presume the insurer (FDIC) will cover far more damages than it should under its current rules.

This incentivizes both depositors and banks to take more risks

on the assumption they will be bailed out if necessary.

But they may be betting on the impossible.

The FDIC’s insurance reserves come from risk-based assessments on bank deposits.

Do they really reflect the risks?

Color me skeptical.

But regardless, the FDIC’s stated goal for its insurance fund is a 2% ratio to insured deposits.

As far as I can tell, that has never happened.

This table shows the ratio’s high since 2002 was 1.41% in 2019.

At the end of 2022 it was 1.27%.

And note well, that’s 1.27% of insured deposits, which are

roughly half of total deposits.

Is that enough? Probably, maybe, hopefully, and then the Treasury would fill any shortfall. But it’s all cloudy and uncertain, and the uncertainty is itself a problem.

Are the nominally “uninsured” bank deposits

safe or not?

People keep asking Janet Yellen and Jerome Powell, and both send mixed signals.

They swing between vague statements of confidence and rote

recitations of current law—which says no, the FDIC limits are firm absent a

“systemic risk” determination.

Nature abhors a vacuum but, in this case, the only honest answer is “Maybe.”

Having had a near-death experience in the last month, some large bank depositors don’t like that answer.

And they’re starting to take matters

into their own hands.

My thoughts on FDIC insurance?

They should raise the limits to $500,000 or $1 million and somehow cover specialty accounts like payroll which must have larger amounts.

Offer a way for larger depositors to buy additional

FDIC insurance.

The key point is to avoid privatizing profits and socializing losses.

If you want guarantees, someone (customers or banks) needs to pay for them.

I see that hand: “John, won’t that mean customers change their banking habits?” (chuckling).

Yes, that’s precisely the point.

When large banks get implicit guarantees small banks don’t have, it changes the competitive balance.

That MUST change.

“We’re Going to Have a Crisis”

When you see your life flash before your eyes, the natural reaction is to become more cautious.

The owners of about $10 trillion in

uninsured bank deposits, now realizing it is at risk, are looking for new

arrangements.

This comes as some of those depositors were beginning to notice they could get significantly higher yields in non-bank instruments like Treasury bills and money market funds.

Bank rates have always been lower but the spread matters.

Moving money out of your bank for an additional 1% yield might not be worth the trouble.

Triple that difference and it becomes more

tempting.

So, we have two different but complementary forces at work: safety and yield.

Both are pulling money out of banks, particularly small banks.

If yield is your priority, your best bet is to move out of banks into Treasury securities, money market funds, and other short-term debt instruments.

If you

absolutely want safety, then Treasury bills are probably still your best bet.

But there’s a third force: convenience.

Or maybe “inertia” is a better word.

Many folks, even some wealthy ones, just default to keeping their money in a bank.

The fact you read an investment newsletter says you probably aren’t in that category but it does exist.

Combine it with the businesses who need to keep their working capital quickly accessible, and a lot of cash is firmly attached to banks.

Again, larger businesses need to maintain payroll

accounts, which is why they should be a separate category.

This cash can choose which bank gets it, though, and recent events are sending a loud and clear message.

To adapt that famous Animal Farm quote, “All banks are safe, but some banks are safer than others.”

That’s not a fallacy.

It is very clearly correct, and the safer banks

are the ones whose failure would be a “systemic risk” that allows for expanded

FDIC coverage.

This isn’t an accident.

This is the system Congress established in the Dodd-Frank Act after our last banking crisis.

It put some additional requirements on the “SIFI” (Systemically Important Financial Institution) banks.

Are they really any safer?

It’s hard to know.

But they are being perceived as safer in terms

of getting the FDIC to cover your over-the-limit balance, so they are where

money is flowing.

Four years ago I wrote what in hindsight may be one of my most important letters: Capitalism Without Competition.

I talked about how the Fed’s interest rate manipulation was increasing concentration in industries like airlines, retail, health insurance, food, and more.

The result is always the same: higher prices and/or lower quality.

And it happens because government

policy protects politically powerful oligopolies from smaller competitors.

The same is true in banking.

A handful of megabanks already hold most of the deposits and they are getting even more, at the expense of community and regional banks whom customers perceive (not wrongly) as less likely to be bailed out.

This reduces the competition that leads to better

service and lower prices for everyone.

Again, this isn’t happening by accident.

It is a policy choice.

It’s not the only choice but it’s the one our leaders have made.

In fairness, let’s assume they meant well in Dodd-Frank.

Maybe it was the right response in 2010 but that was more than a decade ago.

It’s clearly due for a rethink.

We need to safeguard the banking system without giving

advantages to some banks over others.

This rule that lets regulators subjectively decide to insure what would otherwise be uninsured deposits is a problem.

Better to have a base benefit with no exceptions and let large depositors buy additional coverage.

If

they choose not to and their bank fails, it will be their own responsibility.

I am not optimistic for that or any other solution, though.

Our political system is sadly not up to the task.

The current structure is all we

have, and it won’t improve until a crisis forces change.

And the situation demands changes.

Which means—and I don’t say

this lightly—we’re going to

have a crisis which will give us that change.

Which brings to mind the old line: “Change, why change?

Aren’t things bad enough already?”

These words were (apparently) spoken by the then-Prime Minister Lord Salisbury in the late 19th Century.

Renowned for his cynicism, he certainly lets his feelings be known about the

benefits of changing the status quo in the situation he found himself in.

Most larger players don’t really want change.

The status quo is working for them.

Not until a crisis will they bend and then demand change

although they will still want it to benefit them (don’t we all?).

I can’t claim to know exactly what will happen, or when.

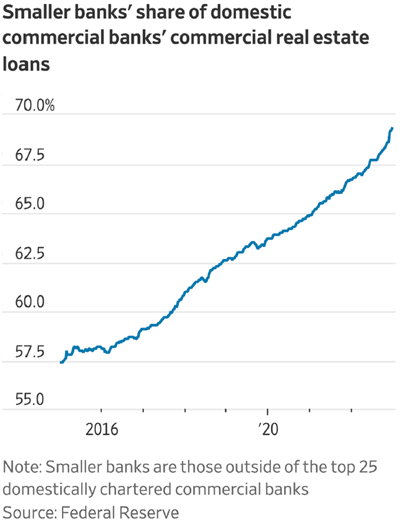

I foresee big problems in commercial real estate, where small banks have a critical role and losing them may haunt us.

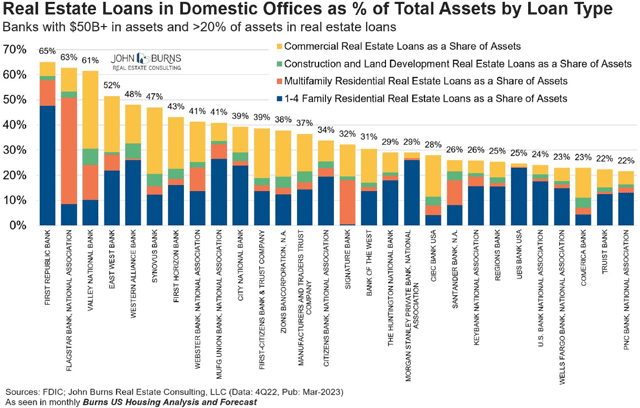

Look at this chart:

Source: Dror Poleg

Breaking that down by components, we find some banks seem to specialize in various types of commercial real estate: from residential to construction to commercial.

Which makes sense as each of these areas has its own nuances.

I know one bank quite well which has one group focused on online sports gambling companies.

Others focus on energy, etc.

Source: Dror Poleg

Office buildings in some large urban areas are a real problem.

The work-from-home trend is reducing demand for office space.

Landlords are beginning to default.

Dror Poleg writes:

“This leaves the bank in a bind.

What seemed to banks like conservative investments in 2021 is now a ticking time bomb that threatens to destabilize their business.

The valuations of many office buildings have dropped or will likely drop considerably.

And government

bonds are much cheaper now than they were two years ago.

“Most office buildings will be ok, and some will do better than ever.

But that doesn't solve the problem.

To maximize their value, owners must introduce new services and amenities and embrace flexibility.

This costs money.

And more importantly, it changes the nature of the asset.

Offices are no longer a ‘monopoly’ asset with stable, bond-like returns.

Instead, they are more like a retail or

hospitality business—with more volatile income and shorter-term commitments

from customers.

“The challenge for banks is not

that offices are worthless but that they are riskier than they assumed.”

And customers are demanding more services and amenities for longer-term leases.

Some areas will see reduced rents.

There’s a slow train

a-coming pulling change behind it.

Now look at what else we know.

The Fed is forcibly deleveraging a highly leveraged economy.

The government is in debt up to its ears.

The political system is both divided and paralyzed.

Demographic trends are colliding with new technologies like artificial intelligence.

Our biggest trading partner, China, is rapidly becoming an adversary with its own shaky economy.

Europe and European banks are much worse.

In short, we have a lot of moving parts right now.

Some of them

are going to clash.

That’s what’s on my mind as I plan the Strategic Investment Conference.

The timing for early May couldn’t be better.

It would have been an entirely different event if we’d had it in February.

I’m designing an agenda

and assembling a faculty with the insight you need as the crisis draws closer.

I’ve often said conferences are my personal art form.

Just as a painter uses color and texture to make something beautiful, I use minds and voices to produce ideas.

I combine people with quite different perspectives, start a conversation, and

then watch the magic happen.

Longtime readers know I’ve been predicting a “Great Reset” in the 2030s that resolves our massive unpayable debts.

I’ve also said things would get bumpy before we get there.

We have taken an off ramp to a different kind of road.

The nice smooth highway is behind us. From here on, it’s going to get uncomfortable.

We will all need to think the unthinkable.

Join us at the SIC and get ready for this ride of a lifetime.

Austin, Dallas, and ???

I will be in Austin on April 22 to support my friend Joe Lonsdale and the Cicero Institute in their mission to support entrepreneurs by developing policies particularly on the state level to enhance our freedoms and society.

Check out their mission and teams and what they do.

It is

impressive.

And since I will be in Austin, I will likely go to Dallas to meet with the team at King Operating and maybe hold a dinner in both cities for clients and prospects.

Details to follow.

And I have a new grandson in Colorado

Springs that needs to see his Papa John and then maybe another client dinner in

Denver?

Given that I bemoaned the loss of personal bankers, I should note that my friend Joe Goyne of very conservatively run Pegasus Bank in Dallas still operates in that old-fashioned know-your-customer way.

A smallish local bank, it specializes in services for family offices and HNW clients.

Joe complains that his customers occasionally borrow money but pay it back too quickly.

“Hard to keep a loan book.”

Time to hit the send button.

Have a great week!

And read something

just for fun this month!

Your needing to see my gym more analyst,

|

|

John

Mauldin |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario