The Boom Time for Farmers Can Last. Who Will Reap the Rewards.

Agriculture is getting its biggest tech upgrade in generations. Deere, AGCO, and other industry giants stand to benefit.

By Jack Hough

Wind turbines dot the fields at Lisa and J.R. Peterson’s no-till farm. Not turning the soil over can prevent erosion and improve soil quality and yields, but it requires some special planting equipment and more attention to weeds. PHOTOGRAPH BY KC MCGINNIS

OSAGE, Iowa—Late winter in North Iowa brings its own kind of harvest.

The wind blows hardest here in March, and no state reaps more power from it for its size than Iowa.

Beneath towering turbine blades, endless fields of frozen stubble will have to wait at least six more weeks for planting.

The stillness belies a breathless shift in farmer fortunes and food production that has grabbed Wall Street’s full attention.

Welcome to corn country.

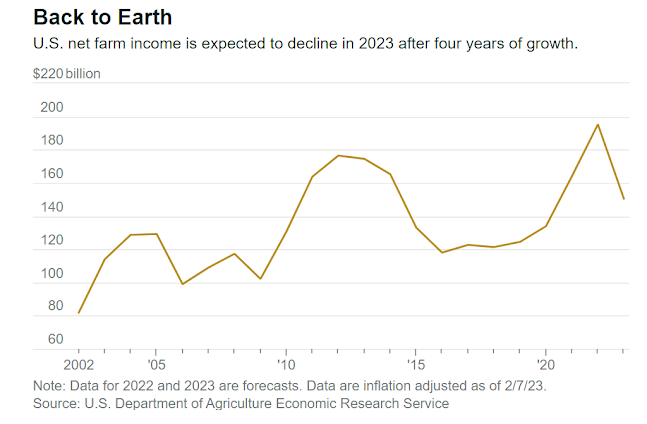

After a decadelong slump, U.S. growers appear to be headed for a third consecutive year of healthy pay. Key crop prices are off last year’s highs but are expected to remain well above historical averages.

The Department of Agriculture puts this year’s expected net cash farm income at $150.6 billion.

Adjusted for inflation, that would be down from last year’s record $195.3 billion, but above the 20-year average of $130.5 billion.

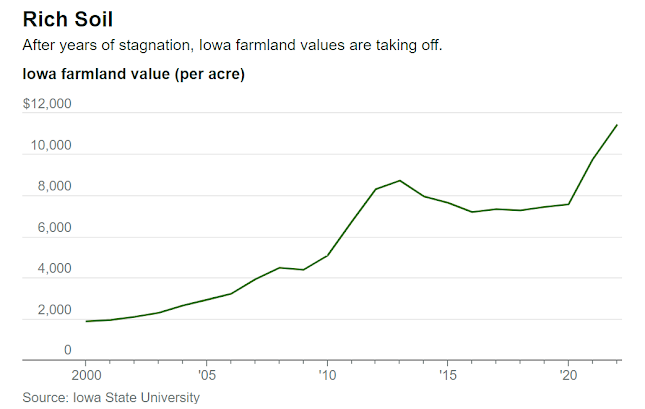

Farmland prices in Iowa shot up 17% last year and 29% the year before.

The average acre recently went for $11,411, around triple the national price.

That figure includes pastures for grazing.

Choice cropland has been selling for over $20,000 an acre, and one Sioux County parcel, perhaps an outlier, hit $30,000 in November.

Beneficiaries include more than locals. Farmland Partners (ticker: FPI), a real estate investment trust valued at close to $600 million, has returned 82% cumulatively over the past three years, more than twice as much as the S&P 500 index.

Pension funds are riding big gains on the vast farm acreage they’ve amassed.

So are Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

Beyond the inflation-fighting ability of land, it isn’t difficult to see why tech titans would warm to agriculture.

Artificial intelligence will one day fill city streets with robocars, but that remains a distant vision.

In farm communities, planters, sprayers, and combine harvesters could run themselves by the end of the decade.

Already, powerful new software can hold down pesticide, fertilizer, and seed costs while raising crop output.

That’s fueling gains for the likes of Deere DE 2.12% (DE) and AGCO AGCO 1.05% (AGCO).

One reading of these trends is that another agricultural cycle must be close to cresting, and a return to lean years isn’t long off.

A competing view is gradually gaining credence: that we’ve entered the most rapid change in food production since the rise of mechanized farming.

That bodes well for the U.S. economy, and family food budgets.

Opportunities remain for investors.

The Benefits of Biotech

On a dead-straight road between near-identical fields, J.R. Peterson holds the wheel of his Ford F 4.22% pickup with one hand and points with the other to the lighter sheen of the land on the right.

That’s a no-till farmer like himself, he explains.

Not turning the soil over can prevent erosion and improve soil quality and yields over time, but it requires some special planting equipment and more attention to weeds.

Farming is filled with these trade-offs.

Corn and soybeans are often grown in rotation, and corn is more profitable at the moment, making it tempting to switch.

But corn is also greedy for nitrogen, which soybeans add to the soil, reducing the need for fertilizer, the price of which has shot up.

Plus, rotating crops can fend off plant diseases.

Peterson has Montana roots.

“I kind of married the queen of Iowa,” he says.

He met his wife, Lisa, through a youth organization called FFA, or Future Farmers of America—she would later serve as its president.

Today, they raise three kids and, with help from Lisa’s 81-year-old dad, run a midsize farm—less than the 600 or 700 acres typically needed to be full-timers, assuming no livestock.

Ethan, 15, flies a drone to check on crop conditions.

For much of the past four years, Lisa was the only woman in Osage driving big rigs to the grain elevator come harvest time; now there are two.

Lisa also works for Pivot Bio, a start-up that uses soil microbes to reduce the need for nitrogen fertilizer.

J.R. works for Syngenta, a seed and pesticide giant.

“Our kids will wear shoes every year, no matter what the price of corn is,” he says with Midwest understatement.

The Petersons added to their acres just before the recent spike in prices and interest rates.

Many farmers are in it for the lifestyle, fewer do it for a living, and the Petersons are somewhere in the middle.

Osage’s population of 3,600 hasn’t grown since the 1950s, but the town feels warmer than some of its neighbors, and J.R. points to one of them to explain why: “They don’t have a school left anymore, which kind of starts to rip the heart out of the town.”

“Biotech is helping the world’s environment, period,” says Chris Edgington, chairman of the National Corn Growers Association. PHOTOGRAPH BY KC MCGINNIS

“Biotech is helping the world’s environment, period,” says Chris Edgington, chairman of the National Corn Growers Association. PHOTOGRAPH BY KC MCGINNISJust northwest of Osage, in St. Ansgar, Chris Edgington wears two hats: industry advocate and farmer.

As chairman of the National Corn Growers Association, he has Mexico on his mind.

A recent push there to ban imports of genetically modified corn for human consumption would violate the trade agreement that replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement, or Nafta, in 2020.

Biotechnology, says Edgington, has accelerated the shift to no-till farming and other eco-friendly practices.

“Biotech is helping the world’s environment, period,” he says.

Long term, rising protein demand worldwide bodes well for farmers.

Most corn, like soybeans, goes to feed livestock, including laying hens.

Biofuels such as corn ethanol are another big demand driver.

Edgington says aviation fuel is a growth opportunity.

Nationwide, there has been a lively debate over ethanol mandates for fuel and their effect on food inflation.

Edgington points out that U.S. food costs remain well below Europe’s.

People and governments like low-cost food, but that doesn’t mean that farmers should get low incomes, he says.

“That’s not fair to the guy who just put his entire life at risk every spring when he started planting.”

In his other role as farmer of 4,000 acres split among five families, Edgington says that finding workers is a challenge.

Some Iowa farmers have turned to a faraway source—South Africa, where English-speaking tractor drivers are plentiful and rising violence has many looking for overseas work.

Rising costs are another concern, and not just for farm inputs—Edgington says health insurance for himself and his wife is $1,900 a month.

Equipment has been in short supply, but farmers are upgrading where they can.

Edgington unboxes what looks like a chunky iPad.

This is a data-monitoring and control system from Precision Planting, a unit of AGCO.

The device will operate a new planter on the way from Case IH, a unit of CNH Industrial CNHI 1.86% (CNHI), which is controlled by Dutch holding company Exor (EXO.Netherlands).

The planter replaces a 2008 Deere model bought in 2014.

Edgington says it will boost his planting speed from 4.5 miles an hour to 8.5 or 9, while improving seed spacing.

“If I want them six inches apart, they will be six inches apart,” he says.

“In my old planter, they would be six, four, two, four, six.”

The Precision Planting system, called 20|20, can diagnose field conditions in real time to keep planting depth the same across different soil conditions; optimize seed frequency for the amount of organic matter in soil; reduce fertilizer use where appropriate; and more.

That can cut costs and boost harvests.

Deere tried to buy the former Monsanto unit in 2015, but was blocked by regulators, and AGCO nabbed it in 2017.

Today, it’s a source of rapid growth in retrofits that started with planters and has spread to sprayers and combine harvesters.

Old machines get new modules, and a control system ties them together.

“No matter what brand and equipment you have, we can upgrade it with new technology to give you new capability,” AGCO CEO Eric Hansotia told Barron’s this past week from Brazil, a major tractor buyer.

The strategy is a good match for the moment.

Only 5% to 7% of farmers purchase a new machine each year.

He says that Precision can upgrade others, with a payback period of around two years.

A new data app called Panorama will tie in with platforms from Deere, CNH, and others.

It was introduced at Precision’s yearly winter conference in January, which investment bank BMO Capital Markets called eye-opening, both for its “rock concert” attendance and for how much ground the company has gained on the competition.

Making Good Land Better

The U.S. leads the world in corn production, and Iowa leads the U.S., followed by Illinois and Nebraska.

It’s a close second in soybeans, behind Illinois.

The land here was always good, and has gotten better with new drainage techniques, says Brendt Warrington, the chief information officer at Saratoga Partnership in Lime Springs, about 45 minutes northeast of Osage.

The business started as a home farm bought in 1958 by a couple 220 miles away.

They made the trip in an Allis-Chalmers WD-45 tractor with three kids and two box wagons.

Top speed: about 10 miles an hour.

Saratoga still has the tractor.

Today, the partnership manages farmland on behalf of owners who are looking for hassle-free income.

It typically leases its tractors and combines—which get their name from combining reaping, threshing, and winnowing to turn grain harvesting into a single job—but buys its trucks and tillage equipment.

Leasing costs Saratoga more than buying, but the goal is to turn over machines often enough to avoid costly breakdowns during crucial planting and harvest days.

Warrington used to be a Deere dealer.

Seed and fertilizer prices could ease a bit, he says, but the rapid run-up in machine prices is unlikely to reverse.

“As far as we’ve come in technology, which is a huge step, it’s a drop in the bucket to what we’ll see in the next five to 10 years,” he predicts.

Farming equipment lines the lot at Deere dealer Midwest Machinery in Wanamingo, Minn. Pandemic bottlenecks and a chip shortage have kept sales behind demand and prices high. PHOTOGRAPH BY KC MCGINNIS

Farming equipment lines the lot at Deere dealer Midwest Machinery in Wanamingo, Minn. Pandemic bottlenecks and a chip shortage have kept sales behind demand and prices high. PHOTOGRAPH BY KC MCGINNISWhen the last farm boom ended a decade ago, Deere suffered three straight years of declines that took revenue down by a third.

This time, pandemic bottlenecks and a chip shortage have kept sales behind demand and prices high.

That has made for an excellent two years for Cory Ziegler, used-equipment manager at the Wanamingo, Minn., office of Deere dealer Midwest Machinery.

“Starting about November of 2020, it was almost like you flipped a switch,” he says.

Asked what he’d like to have more of, Ziegler says sprayers and planters.

Asked about the priciest thing he sells, he points to a shelf with toy combines.

The real thing can cost upward of $1 million.

Deere is a large-cap equipment maker with a hand in construction machines and home mowers, as well as farming.

AGCO is a mid-cap farming pure play.

Its machines include the high-end Fendt brand in Europe, which it’s taking worldwide, and the better-known Massey Ferguson line.

The company also makes grain-storage systems and equipment for feeding and watering animals.

It recently raised the goal for its Precision business to $1 billion in high-margin revenue by 2025; total company sales by then are forecast to be $14.6 billion.

Deere trades at just under 14 times projected earnings for the next four quarters; AGCO, closer to 10 times.

Lawrence De Maria, who covers capital-goods makers for investment bank William Blair, is bullish on both, along with dealer Titan Machinery (TITN), which also changes hands around 10 times expected profits.

The current fleet of farm machines is 10% to 20% older than its historical average, and although financing rates are up, so are trade-in values.

Farm-machinery companies are in their best strategic position since the onset of the Green Revolution that raised crop output following World War II, says De Maria.

“They’re in the field touching the data,” he says.

“They’re able to charge more for their services over time.”

As De Maria sees it, the industry could shift toward more of a farming-as-a-service model, managed from the farmhouse, as machines gain autonomy later this decade.

Lisa and J.R. Peterson amid some of their farming machinery. Many farmers are in it for the lifestyle; fewer do it for a living. The Petersons are somewhere in the middle. PHOTOGRAPH BY KC MCGINNIS

Lisa and J.R. Peterson amid some of their farming machinery. Many farmers are in it for the lifestyle; fewer do it for a living. The Petersons are somewhere in the middle. PHOTOGRAPH BY KC MCGINNISBack in Osage, the 1869 Cedar Valley Seminary built by Baptist settlers has dodged the wrecking ball twice.

The first time, in 1966, the townspeople voted to make it a museum.

The second, in 2016, when the space was needed to expand the nearby elementary school, citizens put the entire 633-ton affair on a massive raft of dollies and moved it 900 feet.

Today, it holds a coffee shop and plenty of meeting space upstairs.

There, Barry Christensen, a farmer and seed seller for Pioneer, a unit of Corteva CTVA 0.24% (CTVA), explains that starting conditions for planting are good, but that farmers’ livelihoods can depend on the rain that falls in late June through July.

Just 15 years ago, getting only half the ideal amount of rain could have been a disaster. Today, not so much.

Hybridized plants are better at handling drought.

Pioneer uses high-speed computers to predict the performance of genetic traits, then breeds the most promising ones for lab and field testing.

A result has been seeds that, for example, resist pests, and can make do with less spraying.

J.R. Peterson—the former Montanan who married corn country royalty—is at the seminary, and says that biotech opponents aren’t following the science, but what really matters is keeping options open.

“If somebody wants to pay $9 a gallon for organic milk, fine,” he says.

“But don’t remove the choice from the mom who has to choose between kids who get to eat because she’s on food stamps.”

Later, at the Peterson house, J.R. brings up Lisa’s dad when asked if this is a golden age for farming.

“He started with horses, and when he farmed, it was open-cab tractors, and he swore he’d never come back to the farm,” he says.

Now, he climbs into a temperature-controlled cab, and after adjusting some settings, takes his hand off the wheel while the planter drives itself.

“If you think about that progression, he looks at it and says the golden age of agriculture is tomorrow.

It will always be tomorrow.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario