Hard or Soft Landing? Some Economists See Neither if Growth Accelerates

Upturn would require higher interest rates to tame inflation

By Nick Timiraos

The Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates at the fastest pace since the early 1980s./ PHOTO: ERIC LEE FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates at the fastest pace since the early 1980s./ PHOTO: ERIC LEE FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNALEconomists rang in the year debating whether the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest-rate increases would steer the highflying U.S. economy into a hard or soft landing—forcing inflation down through either a painful recession or a gentler slowdown in growth.

Surprising strength in hiring and consumer spending last month, together with signs that demand for autos and housing might be stabilizing after a decline, now have some economists pointing to a third scenario that seemed improbable just a few weeks ago: an economic growth upturn.

“A ‘no-landing’ scenario is a present-day reality,” said Neil Dutta, an economist at the research firm Renaissance Macro.

While many Fed officials said they still expect the economy to slow this year, Mr. Dutta said he sees “a huge reluctance to admit the obvious, which is that the economy is reaccelerating, full stop.”

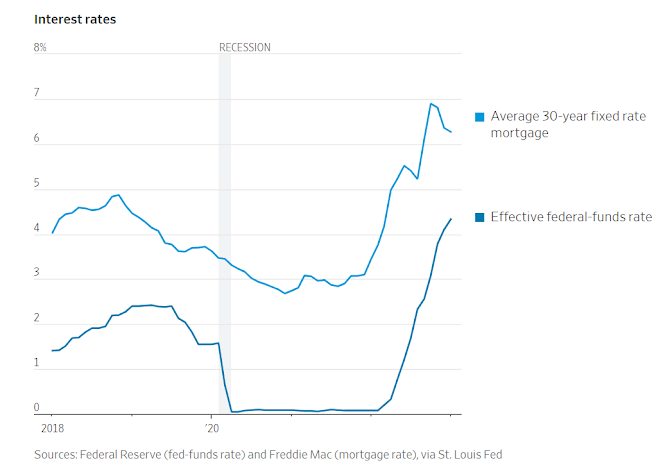

The Fed has raised its benchmark federal-funds rate by 4.5 percentage points since last March, most recently to a range between 4.5% and 4.75%.

That is the fastest pace since the early 1980s, and one that many economists anticipated would slam the brakes on investment and hiring.

But hiring has chugged along recently.

The Labor Department reported this month that employers added a robust 517,000 jobs in January and that the unemployment rate decreased to 3.4%.

Job openings in December rose.

The reports shocked forecasters because previous releases had suggested that climbing interest rates were beginning to curb hiring, said Marc Giannoni, chief U.S. economist at Barclays.

The latest figures suggest that Fed policy “has gained less traction against labor demand than we expected,” he said.

For the Fed, the concern is that companies will be able to keep passing along higher prices to customers as total household income rises.

Meanwhile, as spending shifts from goods and toward labor-intensive services, employers’ demand for workers could keep rising.

While wage growth slowed in January, there was an increase in average weekly hours worked, which led aggregate weekly payrolls, a proxy for wage and salary income, to rise 1.5% last month and 8.5% over the past 12 months.

An index of aggregate weekly hours in manufacturing rose 1.2% in January, suggesting that factory activity rebounded last month.

Economists at Goldman Sachs said last week that they now see a 25% probability of a recession over the next 12 months, down from an earlier estimate of 35%.

The bank expects inflation to fall to 3% this year, with the unemployment rate rising modestly to 4% as long as the economy grows at a pace below its long-run trend of around 2%.

“If we see a reacceleration to trend or above-trend growth—and I don’t think we have so far—then, yeah, we would worry it would be hard to get inflation close enough to 2% to say we can have a soft landing,” said Jan Hatzius, Goldman’s chief economist.

A growth pickup could lead the Fed to raise rates more than it would do otherwise to slow inflation to its 2% goal over the next few years.

“In our view, ‘no landing’ is just a soft or hard landing waiting to happen,” said Ellen Zentner, chief U.S. economist at Morgan Stanley, in a report Friday.

“The longer this plane circles at 30,000 feet, the bigger the risk of running out of fuel,” he said.

“A more plausible scenario is that it is simply going to take more time and tightening to cool off the labor market.”

To be sure, many economists still expect a recession. Some say the Fed moved so fast to raise rates that the economy hasn’t had enough time to reveal the full effects.

The last time it lifted rates to current levels, in early 2006, it took another 1½ years for labor markets to wobble.

“You’re continuing to see pressure on corporate profit margins,” said Kathy Bostjancic, chief U.S. economist at Nationwide.

She expects a moderate recession beginning around midyear as earnings declines prompt job cuts.

Mr. Giannoni of Barclays is now forecasting a recession beginning by the fall instead of by the summer.

He expects the Fed to raise rates by a quarter point at its next three meetings—in March, May and June—bringing the benchmark rate to just below 5.5%, a level last reached in 2001.

Investors in interest-rate futures markets see a 90% chance that the Fed will lift rates above 5% by June, up from 45% a month ago, according to CME Group.

They see a 45% chance that rates remain above that level through the end of the year, up from 3% one month ago.

Many economists have expected consumer spending to sputter as households exhaust savings cushions accumulated during the pandemic. But that might not happen if declining inflation boosts real wages, said Renaissance’s Mr. Dutta.

Last week Mastercard estimated that U.S. retail sales, excluding cars, rose 8.8% in January from a year earlier.

Bank of America said credit- and debit-card spending per household rose a seasonally adjusted 1.7% in January, reversing a 1.4% decline in December.

Higher state minimum wages and annual cost-of-living adjustments for retirees might have contributed to the rise, the bank said.

Consumer spending is showing remarkable stability, said Vasant Prabhu, Visa’s chief financial officer, on an earnings call last month.

While spending on goods has slowed, “services spending really took up all the slack,” he said.

Meanwhile, global economic growth is picking up.

Europe appears to have escaped many of the worst-case scenarios in which skyrocketing winter energy costs would plunge the continent into recession.

China has abandoned its stringent Covid lockdown protocols, which could boost demand for commodities.

Some of the hardest-hit sectors of the U.S. economy are showing signs of life.

Mortgage rates last month drifted lower to just above 6%, down almost a full percentage point since November.

Home builders have cut prices and aggressively subsidized mortgage rates for new customers.

“The obvious question now is will this strengthening of demand continue,” said Ryan Marshall, chief executive at the home builder PulteGroup.

“Home builders are optimists by nature, and I want to believe the Fed can orchestrate a soft landing, but the risk of a recession is real.”

Because inflation was high last year and many contracts for labor and supplies are renegotiated in January, economists at Goldman expect pent-up cost pressures to add an additional 0.1 to 0.2 percentage point to January’s core inflation, which excludes prices for volatile food and energy items.

Omair Sharif, head of the economic advisory firm Inflation Insights, said he sees a risk that core inflation accelerated in January because of potentially large increase in medical-care prices and smaller declines in the prices of goods such as used cars.

Big companies have reported in recent weeks that they have boosted revenue despite falling or flat sales volumes thanks to higher prices.

Unilever PLC, the maker of Dove products and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, said last week that its sales revenue was up 9% in the fourth quarter from a year earlier, because even though volumes fell 3.6%, prices rose 11%.

PepsiCo Inc. reported an 11% increase in sales as prices on average rose 15% despite flat sales volumes.

The threat of a recession later this year might lead companies to boost prices more aggressively in the coming months.

“If you’re trying to recoup higher input costs, this might be your last chance,” said Mr. Sharif.

“You may not get another chance in six months.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario