It is the west’s duty to help Ukraine win this war

We can afford it, and backing Kyiv will be less expensive in the long run than allowing Putin to prevail

Martin Wolf

Ukraine has survived the onslaught of its brutal foe.

It has humiliated the Russian army and regained much lost territory.

These are huge achievements.

But the war is not over.

On October 10 Russia launched a new phase, with its destruction of civilian infrastructure.

Its aim now is to break the will of the Ukrainian people.

This, too, must fail.

The principles of postwar European life are at stake: borders may not be changed by force and citizens may not be prevented from choosing those who rule them.

In addition, if Russia were to win, it would sit on Europe’s eastern border under the rule of a revanchist tyrant.

But, if Ukraine were to win, it would be a potent bulwark against Russia. This war,

then, is existential — not just for Ukraine, but also for Europe.

The west needs to ensure that Ukraine survives and then thrives as a prosperous and democratic nation.

This is not just a moral necessity, but in its interests, too.

There has long been concern about the country’s corruption.

But the way Ukraine has mobilised to fight this war shows that this is not the country we now see.

A corrupt oligarchic state does not organise and fight as this one has.

Ukraine deserves the benefit of the doubt.

It has been remade in war. It will surely be remade in peace as well.

Yet Ukraine cannot win on its own.

It needs military equipment, help with repairing vital infrastructure and, not least, budgetary support.

It also needs continuing pressure from sanctions on Russia’s economy and military might.

It will need great help, too, with rebuilding, as it seeks a life within the European family, a life its people’s struggles have earned and one that will bring huge benefits to Europe itself.

The damage has been extraordinary.

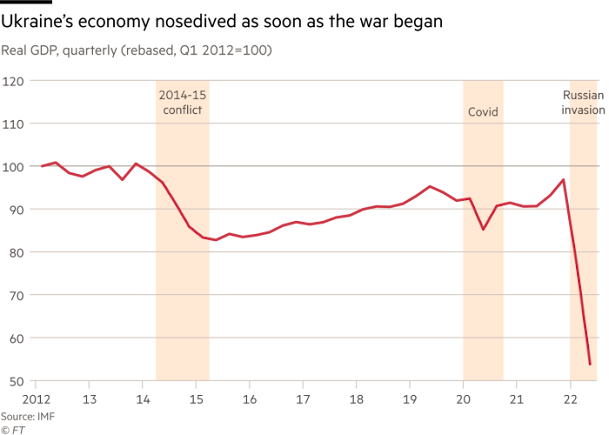

Ukraine’s economy has shrunk by about a third this year, with an inevitably large impact on tax revenues.

In a report published in October, the IMF notes that about a fifth of the population has emigrated, with a similar number internally displaced.

The country faces huge expenses in fighting the war and repairing damage today.

All this has devastated the public finances.

So long as the war continues, so, too, will the costs.

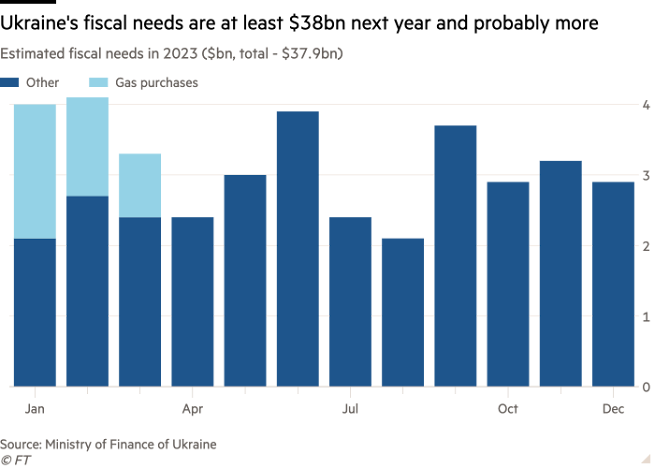

Ultimately, there will be a huge bill for reconstruction. (See charts.)

The finance ministry has done a more than creditable job in managing the fiscal situation.

Yet it has had to rely on monetary financing of the fiscal deficit, foreign currency reserves are near zero and inflation in the year to December will be some 30 per cent.

The IMF estimates that if all goes well, the country will need $40bn in external fiscal support next year, plus $8bn for repair of infrastructure.

If all goes badly it will need roughly an additional $9bn.

The EU is expected to commit €18bn in fiscal support for next year.

The US administration has asked Congress for $14.5bn to September 2023, with more expected for the balance of 2023.

Member countries of the EU, plus others (Japan and the UK, for example), and international financial institutions should give more.

Even so, the external budgetary support will only be enough if all goes well.

It is evident that things could go far worse if the Russians managed to inflict far more damage on the economy than they already have.

The EU also wants conditionality, to ensure macroeconomic stability, good governance, the rule of law and reform of the energy sector.

It is open to question whether such conditionality makes sense in a hitherto successful war of survival.

In any case, partly for this reason, the EU also wants an IMF programme, as much as a catalyst for reforms as for the money.

Meanwhile, the fund feels constrained by its articles of agreement, which require a programme ensures sustainability of the balance of payments, as well as safeguards that money will be returned.

In such a war, neither is sure.

One might envisage three ways out of this impasse: one is that western shareholders guarantee the IMF against losses; a second is that the IMF is more creative and lends anyway; the last is that IMF imprimatur comes only from its emergency programmes and what it calls “Program Monitoring with Board Involvement”.

It is right to think about postwar Ukraine, too: the needs of reconstruction and, not least, its financing (partly perhaps from confiscated Russian assets); and the building of a more modern European country and economy.

But the necessary condition for this is continued independence and final victory in the war.

This will take a huge amount of assistance, with greater supply (and so production) of arms, sufficient and reliable fiscal assistance, and a flow of the equipment needed to repair the infrastructure Vladimir Putin will continue to destroy, because that is all he can do.

Ultimately, war is a matter of resources and motivation.

Those Ukraine has: it is smaller than Russia, but it has demonstrated far greater motivation; and its allies have the resources.

The combined gross domestic products of the US, EU, UK and Canada are some 22 times that of Russia.

Even fiscal support of $60bn next year would cost only 0.1 per cent of the allies’ combined incomes.

Who could argue this is unaffordable?

Is it not far more unaffordable to let Putin triumph?

Yes, it is painful to suffer the energy shock from this war.

But it is the west’s duty to cope.

It is Ukraine and Ukrainians who bear the brunt of the conflict.

We in the comfortable west must give them the resources they need.

Only when Putin knows he will not be allowed to win is the war likely finally to come to an end.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario