On Geoeconomics: Systemic Challenges

State actors are starting to behave like aggressive investors in a more deglobalized environment.

By: Antonia Colibasanu

It’s no secret that central banks and governments the world over are dealing with rising inflation and economic uncertainty, both of which need to be addressed head-on if they want to maintain internal stability.

To do so, they are starting to consider measures outside the usual monetary toolkit and that address geopolitical events by stimulating national investment more creatively.

The British government, for example, proposed a deficit-financed expansionary fiscal policy while the Bank of England raised interest rates and reduced its balance sheet to fight high inflation.

The same week, Japan’s Ministry of Finance spent 2.84 trillion yen ($19.5 billion) to slow the slide in the currency – the first such intervention since 1998.

The two countries are the world’s third- and fifth-largest economies, as well as key U.S. allies in their respective regions.

Such news frames the next phase for the global economy, giving several hints to understand how different countries will seek to restructure their economies, a trend that we have written about since 2021.

In other words, state actors start behaving more like (aggressive) investors in financial markets as they defend their interests.

This was common enough in the 1990s, before globalization tightly bound national economies to one another.

But times have changed.

World economies are less globalized than they once were, a trend accelerated but not started by the COVID-19 pandemic and made all the more apparent with the fallout over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Even so, existing trade and technological dependencies limit the extent to which central governments can defend their interests, and all measures they take will affect others faster than they would have before.

There are several systemic challenges the world is facing at once.

The first and most consequential is the weaponization of economic ties.

Global economic warfare continues, and the current energy crisis is just one of its major theaters.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, few anticipated a long-term war, so few believed the global economic war would continue into the winter of 2022.

The sanctions imposed on Russia by the West were supposed to force Moscow into submission.

Instead, they have balkanized the global economy.

Before the imposition of sanctions, foreign-exchange reserves were thought to be untouchable.

At the same time, the U.S. dollar, the world’s reserve currency, was thought to be a sort of public good – as was SWIFT, the globally accepted mechanism for international financial exchanges.

Curbing Russia’s access to both was, in a sense, unprecedented – the West has done this before (to countries like Iran and Venezuela) but not to such an important economy as Russia’s.

For the sanctions to succeed, Russia had to be caught off guard.

It wasn’t.

The ruble initially collapsed, inflation skyrocketed, interest rates soared and output dwindled.

But six months later, Russia’s economy, though bad, seems to be performing better than expected.

Russia had prepared itself for measures like these since 2014, when it invaded Crimea and was thus subject to the first wave of Western sanctions.

Since then, the Kremlin invested heavily in supporting national industry and campaigned internally for the need to increase Russian entrepreneurship and for Russian-made products.

Russia's energy strategy toward Europe since the early 2000s, meanwhile, insulated it from punishment.

After the initial shocks, the world came to understand that both SWIFT and the U.S. dollar are conditional public goods.

The West couldn’t manage to secure alliances beyond the G-7 in a quick manner (which would have helped its rapidly winning the economic conflict against Russia), and though developed economies and the global north have coordinated their actions against Russia, the global south is largely undecided.

In fact, most unaligned G-20 countries have more to gain from playing Russia and the West off one another.

Still, some are trying to find alternatives to SWIFT, while others have found some already.

Put simply, Western control over global financial markets is being challenged, and while alliances are still in the making, uncertainty continues to affect the global economy.

The second systemic challenge facing the global economy is post-pandemic uncertainty.

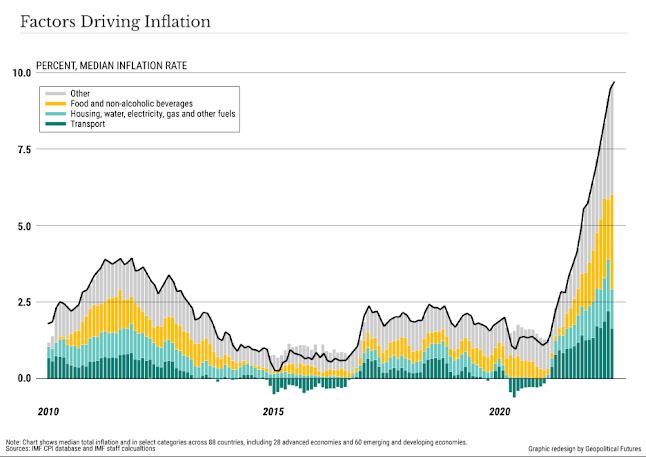

Remember that the current energy crisis is not solely responsible for high inflation.

In 2021, excessively loose monetary, fiscal and credit policies and supply shocks caused prices to surge.

The war in Ukraine only made things worse, of course, but a dramatic decrease in consumption, more than anything, changed the inflation equation in 2022.

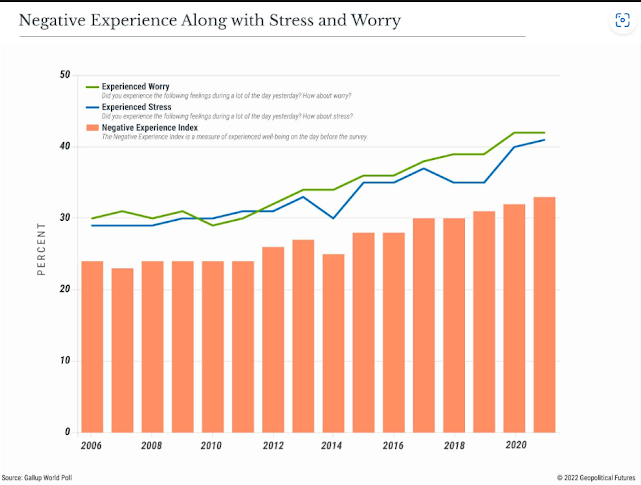

With all polling data pointing to pessimism with regard to the future, consumption is unlikely to recover anytime soon.

Those same supply shocks, meanwhile, are still distressing markets.

Some industries such as shipping have slowly adapted to the new reality, but things like China’s continued lockdowns of major ports have created new bottlenecks that are hard to cope with.

In fact, China’s economic uncertainty is the third major systemic challenge for the world’s economy.

The country has been struggling, of course, but the way it handles its recovery is a point of major contention within the Community Party of China, one so strong that there are rumors of viable opposition to President Xi Jinping at the upcoming National Party Congress.

The relationship between China and the world, and specifically between China and the U.S., its most important customer, is dependent on Chinese politics and its socioeconomics.

The fourth systemic challenge is European fragility.

An economically weakened China and Russia is bad for Europe, which depends on both in different ways.

The European economy never really got over the pandemic, so it never really found a way to mitigate the damage of Chinese supply chain shocks.

The energy crisis is worse, politically and economically, and, with a cold winter coming, is likely to trigger more socio-economic consequences on the Continent.

The key question is the degree to which German industry will be affected by the Nord Stream 1 supplies cut earlier this month – and thus the degree to which the European economy will be affected.

But others to watch are France and Italy.

Many have criticized Paris over its inability to launch a new reform agenda, while Italy just elected a new right-wing government.

Central and Eastern Europe are mostly preoccupied with military threats from Russia, while not excepted from socio-economic troubles.

The last but likely most important systemic challenge is Washington’s weaponization of the U.S. dollar.

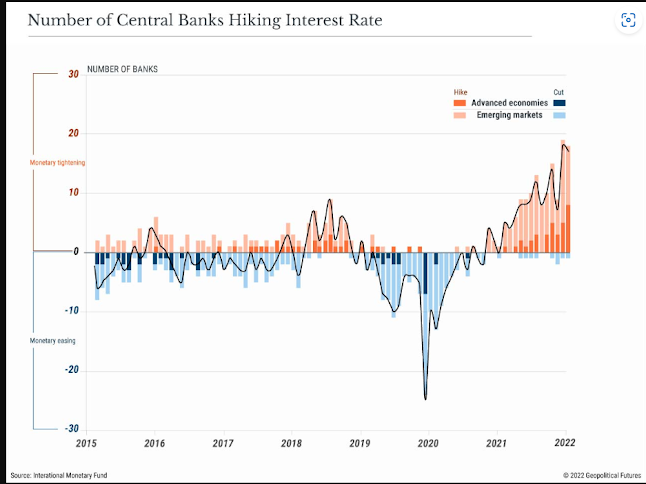

The U.S. Federal Reserve is using all the usual policies to force monetary supply and demand into better balance, focusing especially on interest rates.

While inflation is high and the labor market continues to be tight, the Fed will likely keep tightening financial conditions to slow growth enough to cool the economy, even though this makes for challenging and volatile markets.

The Fed’s hiking rates to bring down inflation is having spillover effects for the rest of the world through the appreciation of and demand for the dollar.

The problem is this kind of weaponization doesn’t discriminate between friend and foe.

When the global economy is stable, this may give countries like Germany, the U.K. and Japan a spark for increasing their exports to the American market.

But the global economy is not stable – and all these countries are fighting back inflation and dealing with similar problems that the U.S. is.

Likewise, the European Central Bank, which is in charge of stabilizing the eurozone, has echoed the Fed policy of increasing interest rates.

At the same time, it has delayed its quantitative easing and bond purchasing programs to make sure countries in Southern Europe like Italy and Greece have the flexibility they need to deal with rapidly changing market conditions.

For them, high interest rates coupled with high debt levels would create poor liquidity in markets where businesses are still recovering from the last decade's economic crisis.

Keeping some monetary stimulus is still key for businesses to continue working in the European periphery, at least until inflation is under control.

The U.K. and Japan, as mentioned, are taking completely different paths.

They’re betting on expansive fiscal stimulus while ensuring funding for energy and critical infrastructure projects.

Instead of increasing the interest rates, they are increasing the borrowing on the governments’ part, looking to subsidize both consumption and investment.

In essence, they are replacing the economic crisis with a currency crisis – which explains recent reports about the pound and the yen dropping to historical lows against the dollar.

By doing that, they have a larger set of tools they can use to address economic imbalances, which are related to both the post-pandemic reality and the war in Ukraine.

Specifically, they’re looking at cyclical sectors like industrials and construction to support the rebound in economic activity.

Considering the systemic challenges that the global economy is facing, the coming winter will be difficult.

With liquidity low and with credit expensive, a recession is likely around the corner.

Recession may be an old game, but deglobalization is not.

That means that in the next few months we will start to see the first signs of the restructuring processes we’ve been anticipating since 2021.

With many businesses cutting down on operations and with governments becoming more active in shaping the national economy, more government spending is up next.

Since most of the developed world has an aging population and thus excess savings, spending on defense and energy infrastructure may come with still-low real interest rates for governments.

But more government spending doesn’t necessarily mean responsible spending or lower inflation.

Expect more uncertainty and investor anxiety in the next months.

Further shocks will determine whether (and how) states become more aggressive in protecting strategic assets and critical infrastructure.

Protectionism will likely become a preferred trade policy, with all the populist and nationalist sentiment that comes with it.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario