Xi Jinping’s Ideological Ambition Challenges China’s Economic Prospects

Many economists predict slower growth, in part due to Xi’s focus on Communist Party control

By Lingling Wei

Xi Jinping laid out ambitious plans two years ago to expand China’s wealth and double the size of the nation’s economy by 2035.

The target would require China’s economy to grow an average of nearly 5% annually over 15 years, according to estimates by officials involved in policy-making.

Many economists inside and outside of China now believe 5% won’t be achievable, not just for this year, but also for the longer term.

A major challenge is Mr. Xi’s political agenda.

Since he rose to power in 2012, Mr. Xi has put ideological rectitude, national security and Communist Party control at the center of policy.

And he has insisted on greater state control over the economy—an approach that many economists say has come at the expense of the dynamic private sector that propelled China’s extraordinary growth.

Private-sector economists, the World Bank and other institutions expect China’s growth to rebound to around 4.5% next year after an estimated 3% or so in 2022, assuming Beijing eventually relaxes its zero-Covid policy.

Many economists predict growth will remain weaker than before the pandemic, in part due to a shrinking workforce and rising debt levels.

Much of the recent slowdown in China’s GDP growth traces to the country’s strict policies to contain Covid.

Mr. Xi’s insistence on lockdowns for even minor outbreaks has underpinned his view that China’s system of centralized control is better than the West, and has kept reported case numbers down.

It has also kept businesses closed and pushed up youth unemployment.

Mr. Xi now looks set to extend his term as the nation’s leader for another five years at a Communist Party congress this week, breaking with recent precedent to step aside after 10.

And he shows few signs of changing course on his priorities.

In a speech opening the party congress, Mr. Xi defended his zero-Covid policy, saying it has “protected people’s lives and health to the greatest extent possible.”

A medical worker sat in a street booth for Covid testing in Shanghai last month. / PHOTO: ALEX PLAVEVSKI/SHUTTERSTOCK

A medical worker sat in a street booth for Covid testing in Shanghai last month. / PHOTO: ALEX PLAVEVSKI/SHUTTERSTOCKOn Monday, China abruptly delayed the release of third-quarter data on its gross domestic product, originally due out Tuesday, without giving any reason.

A longer-term economic concern is that Mr. Xi has prioritized state-owned businesses, squeezing private companies—a major reversal from China’s trajectory since former leader Deng Xiaoping ushered in a period of “reform and opening” in 1978.

He has harnessed the powers of the state to neutralize powerful private-sector tycoons.

Amid rising tensions with the U.S., he has stepped up an effort to reduce China’s reliance on foreign technology and steered more capital into industries that Beijing sees as strategically important, such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence.

The shift is contributing to slowdowns in productivity and wage growth, weakness in China’s financial markets, and growing reluctance by Western companies to invest there.

A new study by the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center, a Washington think tank, and Rhodium Group, a New York-based economic research partnership, predicts that China will struggle to maintain growth of over 3% annually by the middle of this decade, unless the government makes adjustments to overcome a shrinking population and weak productivity.

“We’ve seen a gradually fading enthusiasm for market-based economic reforms,” said Helge Berger, the International Monetary Fund’s mission chief for China. “China’s potential for growth might be substantially lower than what we’re used to.”

Some signs point to trouble for the country’s growth potential.

An IMF analysis estimates that growth in productivity averaged just 0.6% in most of the past decade under Mr. Xi’s watch.

That was a sharp decline from an average of 3.5% in the previous five years.

The IMF estimates the productivity of state firms is only about 80% of private ones, and they’re typically less profitable.

State-owned PetroChina Co., which helps with China’s efforts to reduce foreign energy dependence, has more than 400,000 employees, six times more than Exxon Mobil Corp.

Based on return on assets, the Texas-based company is about three times more profitable than PetroChina, with more than twice the revenue for each full-time worker.

A major push on revamping the state sector, with steps to ensure a level playing field for private firms, could more than double annual productivity growth in China to about 1.4%, the IMF projects.

Mr. Xi’s politics-in-command approach has upset some senior leaders inside China who believe the country should continue down the path set by Deng, according to officials involved in policy-making.

Mr. Xi’s No. 2, Li Keqiang, in what is expected to be his final year as premier, has at times appeared to tap into worries within party ranks about faltering growth.

Shortly after party leaders met in the seaside town of Beidaihe in August, Mr. Li took a trip to Shenzhen, the cradle of China’s economic transformation.

In a symbolic gesture, he laid a wreath at a large statue of Deng.

“The reform and opening-up must be moving forward,” Mr. Li said to a cheering crowd, according to a video widely circulated on China’s social media.

He likened the process of liberalizing China’s economy to “blazing a trail of blood.”

The video was later taken down by Beijing’s censors.

Mr. Xi had signaled a different approach when he took office in 2012.

Eager to boost living standards as part of his “China Dream” for national rejuvenation, he called for state companies to operate more like commercial firms, for cities and provinces to overhaul their finances, and for the government to promote entrepreneurship.

As time passed, Mr. Xi became suspicious of market forces and the way they could threaten political stability, especially after stock market turbulence in 2015, people familiar with his thinking say.

Mr. Xi also grew more vigilant about potential threats to Communist Party supremacy from private-sector tycoons like Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. co-founder Jack Ma, as well as the U.S.’s increasingly tough stance toward China.

Market-oriented changes gave way to initiatives aimed at strengthening the party’s control and making China, in Mr. Xi’s words, a “modern socialist power.”

State-led policies aimed to reduce China’s reliance on Western imports, turn China into a leader in new technologies, wring debt from the financial system and redistribute wealth.

Beijing showered subsidies on favored industries and encouraged state-owned enterprises to merge to become more powerful.

By 2018, total assets at state companies were valued at 194% of China’s gross domestic product—higher than in the early 2000s and several orders of magnitude larger than any other country, according to the IMF.

Because of their state backing, China’s state firms borrowed at lower interest rates.

They now make up more than 90% of bond issuance in China, according to the Rhodium-Atlantic Council report.

Efforts to rein in housing speculation and prevent a property bubble from getting bigger led to state-owned property developers gobbling up market share at the expense of private ones.

Graduates at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan in June./ PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

Graduates at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan in June./ PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES/GETTY IMAGESBeijing also launched a near-blanket crackdown on private technology giants seen as challenging Mr. Xi’s authoritarian rule, especially in sectors that ventured into the party’s ideological domain, such as private tutoring and entertainment.

One entrepreneur who received a Ph.D. in education technology in the U.S. spent more than a decade building up an English-language learning platform in China serving more than 15 million students.

He left the company behind last year after its customer count dropped by 80% in Beijing’s crackdown on private education firms, which Mr. Xi feared were costing parents too much money and in effect becoming an alternative education system.

“It’s like you raise a baby for 15 years, and suddenly it’s gone,” the entrepreneur said.

He has since started work doing research out of a government-funded lab in computational biology, a strategic priority for China.

He is considering a return to the U.S.

Another entrepreneur, Rock Sun, said he left China over the summer after the government outlawed cryptocurrency-related transactions.

Beijing feared that decentralized, anonymous digital currencies could undermine state control over the financial system.

Mr. Sun, who had worked for years at technology and crypto firms in Beijing, said crypto investors had initially welcomed government guidance to help bring order to the industry.

After Beijing’s actions wiped it out, he left for Singapore, where cryptocurrencies are regulated but allowed.

China is now a world leader in some industries Beijing supported, including electric vehicles.

Companies that benefited from state support, including Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Co. and SenseTime Group Inc., are at the cutting edge of fields such as surveillance and AI.

A man stands at the entrance of an office building in front of an computer called Smart AI Epidemic Prevention, made by the company SenseTime, in March 2020. / PHOTO: ALEX PLAVEVSKI/SHUTTERSTOCK

A man stands at the entrance of an office building in front of an computer called Smart AI Epidemic Prevention, made by the company SenseTime, in March 2020. / PHOTO: ALEX PLAVEVSKI/SHUTTERSTOCKVenture-capital investors put $129 billion into Chinese startups in 2021, beating the previous high of around $115 billion in 2018, with most of the money heading into party-approved priorities such as semiconductors and information technology.

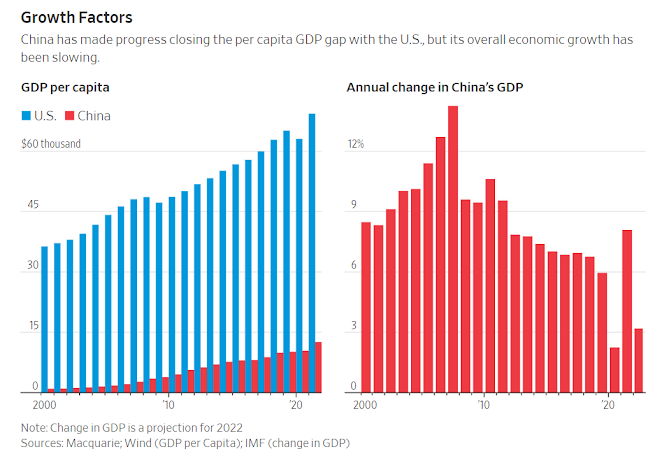

China’s per capita national income reached $12,556 last year.

That puts it closer to the threshold of $13,205 that the World Bank classifies as the minimum for a “high-income” country, a longtime goal for Beijing.

China’s GDP per person was 18% of the U.S.’s last year, compared with 12% in 2012.

Scott Rozelle, an economist who runs the rural education program at Stanford University and co-author of “Invisible China,” said China could find itself caught in the “middle-income trap”—in which a country’s growth stagnates before it gets rich—unless it radically changes priorities to invest in human capital.

He has found that only 34% of China’s labor force had some high-school education as of 2020, a percentage lower than other middle-income countries such as Mexico, Argentina and Turkey.

Among the world’s major market economies, the high-school attainment rate averaged 82%.

“China has failed to invest in its people,” he said.

After Mr. Xi’s efforts to make China less reliant on foreign technologies, the country is now able to make about 26% of the semiconductors it needs, up from 13% in 2017, according to Handel Jones, chief executive officer of consulting firm International Business Strategies.

Those are less complicated chips.

Despite billions of dollars in investments over the past 10 years, China has failed to mass-produce higher-end chips, which are vital to modern economies and currently dominated by chip makers in Taiwan, South Korea and the U.S.

A worker checks semiconductor devices at a Chongqing Pingwei production workshop in March. / PHOTO: COSTFOTO/ZUMA PRESS

A worker checks semiconductor devices at a Chongqing Pingwei production workshop in March. / PHOTO: COSTFOTO/ZUMA PRESSA state-led push to develop China’s first large commercial passenger jet, the C919, has shown limited progress after a decade of investments.

The aircraft recently cleared one of a series of regulatory hurdles to begin carrying passengers, but industry experts say it remains years away from commercial service.

Arthur Kroeber, founding partner of research firm Gavekal Dragonomics who has written extensively about China’s economy, said he’s becoming more negative about China’s outlook given the limited benefits from its technology-centric industrial policy.

“The declared strategy can boost certain sectors such as semiconductors and electric vehicles, but is not enough to create economywide productivity growth,” he said.

Increased regulatory screening of foreign investments, for national security reasons, has led to more multinationals leaving or planning to divest from China.

Despite government data showing continued strong foreign investment flows into China, the Rhodium-Atlantic Council study finds that foreign direct investment as a share of China’s GDP has declined steadily, to 21% last year from nearly 30% a decade earlier.

A survey released in August by the U.S.-China Business Council of 117 American companies operating in China showed that business optimism had reached record lows.

Some 8% of the companies polled had shifted parts of their supply chains out of China to the U.S., according to the survey, while another 16% had moved some operations to other countries.

Mr. Xi has rolled back some of his policies that moved China further away from a market economy, including a “common prosperity” campaign that called on entrepreneurs to share their fortunes.

Mr. Xi has told officials that the near-term goal was about “making the cake bigger first,” and then dividing it more equally, according to officials briefed on the remarks.

“A lot of people are not sure if economic development will continue to be the central task of the party,” said Mao Zhenhua, chairman and founder of rating agency China Chengxin Credit Co., at an economic forum held in Beijing in June, according to a transcript.

“Some course correction is needed for the economy to be back on the right track.”

Karen Hao and Rachel Liang contributed to this article.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario