The Labor Shortage Will Get Worse and May Last for Decades

By Megan Cassella

In the summer of 2020, Mike Zaffaroni, the owner of Liberty Landscape Supply in Jacksonville, Fla., needed to start staffing up to fulfill a pair of contracts to plant trees around the city.

At first the hiring went relatively smoothly, but as fall approached, things started to change: A growing number of candidates were failing to make it to their scheduled interviews.

He would sometimes expect 10 people, but only one would show.

“It’s one of the most alarming things I’ve seen in my working career,” he says.

In the two years since, Zaffaroni has raised his starting wages by nearly 40%.

He expanded his benefits program, shortened his interview process, and began considering a broader pool of workers, including those with limited experience or a spotty work history.

But none of it has been enough: His 112-person company still has 19 current openings and few prospects to fill them.

Now, Zaffaroni is applying for a set of visas that would allow him to hire 10 foreign temporary workers next year—a first for his 15-year-old business.

“I really think that’s the only way to solve the problem in the short term,” Zaffaroni says.

“Because I don’t know that we’re going to pull a whole bunch of workers back into the workforce.”

As the labor market settles into a postpandemic normal, Zaffaroni is among millions of employers across the country still bending over backward to try to hire from a pool of workers that appears increasingly dry.

In July alone, U.S. companies posted 11.2 million job openings for a market that has just six million unemployed workers to fill them, a vast disconnect that has been trending wider for more than a year.

For all of the Great Resignation talk, the workforce has already surpassed its pre-Covid size—but the economy has continued to grow in the meantime, creating fresh waves of unquenchable demand.

Now, the hiring challenges that many expected would fade as the worst of the Covid shocks dissipated look less like a passing trend and more like a new reality.

Economists warn that the U.S. is staring down what will become one of the biggest economic challenges of the next several decades: a permanent—or at least deeply entrenched—labor shortage.

At its worst, the depleted workforce could sandbag productivity and economic growth, hinder the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tame inflation, and even threaten the nation’s status as a global superpower.

“I think a lot of companies are still like, ‘We’ve got to make it through this little blip,’ ” says Ron Hetrick, a senior labor economist with Lightcast who led a 2021 economic report on the forthcoming workforce challenges called “The Demographic Drought.”

“And I’m like, ‘Blip?

Are you kidding?’ ”

Average annual growth of the U.S. prime working-age population is projected to slow sharply to just 0.2% over the next three decades, down from 1% average annual growth over the past 40 years.

By 2100, as much as two-thirds of the country could be out of the workforce and financially dependent on the remaining one-third, according to an estimate from Hetrick and his co-authors.

For companies, persistent labor shortages mean hobbled growth, and for consumers, fewer high-touch services and 24-hour or next-day options.

“It’s not just a matter of having to do more with less,” says Zaffaroni, the landscape-supply company owner.

“It’s having less, and doing less, and productivity actually dropping because you don’t have those resources.”

Mike Zaffaroni’s 112-person Liberty Landscape Supply still has 19 current openings and few prospects to fill them. / Photograph by Malcolm Jackson

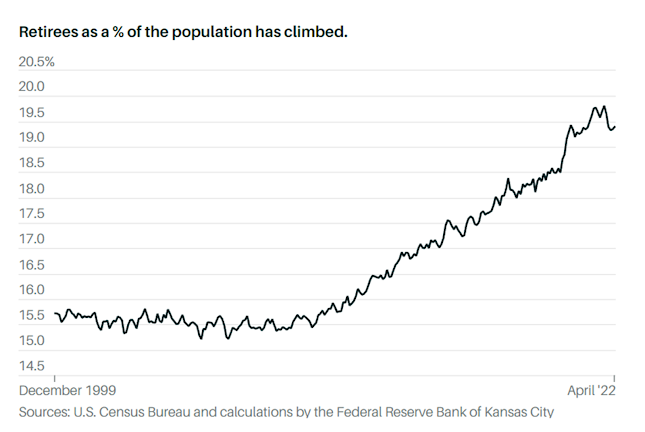

Mike Zaffaroni’s 112-person Liberty Landscape Supply still has 19 current openings and few prospects to fill them. / Photograph by Malcolm JacksonThe concern that the U.S. would one day run short on workers has been circulating for decades, as economists braced for baby boomers to begin retiring around 2010.

As far back as 2001, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston organized a conference focused entirely on the economic impact of demographic change, which included research that found the country would need a 40% jump in labor productivity by the mid-2030s just to maintain then-current living standards.

But since those early warnings, two phenomena have emerged, seemingly tailor-made to take the situation from bad to worse.

The first was that net immigration began to fall, peaking in 2016 before entering a slide it has yet to recover from, eating away at the usual influx of both highly educated scientists and engineers and manual laborers.

A handful of factors drove the decline.

U.S. border enforcement increased at the same time that economic development in Mexico and Central America meant that fewer people there were looking to leave the region, says Giovanni Peri, a labor economist with the University of California, Davis.

A shift in immigration policy and rhetoric under President Donald Trump—including lower caps on refugees and a litany of attacks on the H-1B visa program, which provides green cards for highly skilled workers—also contributed.

Then came Covid.

As the pandemic drove up the death rate and dragged down the birthrate, it inflamed the pre-existing demographic trends: From July 2020 to July 2021, the U.S. population grew just 0.12%, according to an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by demographer and Brookings Institution senior fellow William Frey—the lowest annual rate since World War I.

The virus also hit the workforce on other fronts: Kansas City Fed researchers estimate there were 2.1 million “excess” retirements during the pandemic, meaning those above the expected trend.

And as more Americans have stayed home for reasons ranging from long Covid to caretaking responsibilities, the labor-force participation rate has dropped from 63.4% just before the pandemic to 62.4% in August, the Department of Labor said on Friday; the agency forecasts that the rate will slide to 60.4% by the end of this decade.

Covid exacerbated the immigration problem, too.

The combination of closed borders and shutdowns at U.S. consulates overseas led to massive visa backlogs that remain today, pushing net migration to its lowest level in decades.

Peri’s research found that by the end of 2021, there were roughly two million fewer working-age immigrants in the U.S. than there would have been had prepandemic trends continued, half of which would have been in highly educated science, technology, engineering, and math, or STEM, fields.

“When we look at the trend lines, and the difficulty that we’re going to have getting the workforce participation rate back to where it was even prepandemic—the demographic trends and the shortfalls in legal immigration—we think all of that kind of points to this being a long-term challenge for the American economy,” says Neil Bradley, chief policy officer with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

The Chamber is among a growing chorus of major businesses, lobbying groups, and economists calling on lawmakers to take steps to ease the labor crisis, with proposals for comprehensive child-care, federal investments in job training and reskilling, and a host of other policies.

But some of the loudest calls are for Congress to find ways to boost legal immigration, either by raising the annual cap on temporary work visas or passing wholesale reforms to offer more pathways into the U.S.

Immigration has been thrust to the forefront because many employers see it as the most efficient way to increase the pool of workers quickly and substantially.

(Efforts to increase the domestic birthrate, for example, would be of little help to them for another 20 or so years.)

Foreign-born workers also play an outsize role in specific industries that, without substantial policy changes, could face a crisis in the coming years.

Take healthcare.

As of 2018, immigrants constituted 17% of the overall U.S. workforce but 38% of home health aides, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

And the Bureau of Labor Statistics sees the home health-aide industry growing by 33% from 2020 to 2030—a spike driven by the aging population.

Already, however, the healthcare and social-assistance industry has nearly two million unfilled jobs and, at 8.8%, one of the highest rates of open jobs anywhere in the economy.

“You have not only a retiring population, but a retiring population that really needs advanced services…that an immigrant typically fills,” says Hetrick, the “Demographic Drought” economist.

“They’re just not there, at the time when we probably need them more than ever.”

Construction is another sore spot.

In July, there were 375,000 job openings in the industry for 359,000 unemployed construction workers, Department of Labor data show.

And that’s poised to balloon: McKinsey estimates that the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which Congress passed in November, could create 300,000 to 600,000 new jobs a year for the next decade.

Failing to meet that demand will hold back progress on modernizing the country’s infrastructure—which the Biden administration has argued is necessary for easing supply-chain issues—and on replenishing the U.S. housing supply, where lack of availability is keeping rent and shelter costs elevated.

But the situation is perhaps most damaging in STEM professions because of the impact that innovation has on U.S. productivity and broader economic growth—and because of the way foreign-born workers dominate these fields.

Immigrant students receive more than half of all master’s degrees and 44% of all doctorates in STEM fields, the Congressional Research Service found in 2019.

And despite headlines about tech layoffs or hiring freezes, the industry remains desperate for skilled workers: On the job-search site Indeed, postings in software development alone are up 92% since February 2020, while listings in industrial, civil, and electrical engineering are all up roughly 80% during the same period.

Overall, the Department of Labor estimates that the STEM sector will need 1.1 million additional workers by 2030.

Leaving these positions vacant hurts more than just the tech industry.

Peri cited research out of the University of California, Berkeley, that finds that every new job in high-skill fields, including STEM, creates 2.5 more jobs for the local economy.

“From an economic point of view, this is the driver of American productivity,” he says.

“The shortages in this group will generate, eventually, smaller economic growth for everybody else.”

Liberty Landscape Supply is looking to hire foreign temporary workers. / Photograph by Malcolm Jackson

Liberty Landscape Supply is looking to hire foreign temporary workers. / Photograph by Malcolm JacksonOpening the immigration spigots would require significant action from Congress on an issue that lawmakers have failed to address in a comprehensive way since 1986, when President Ronald Reagan granted amnesty to nearly three million people.

Since then, President Barack Obama used executive power in 2012 to offer work permits and renewable deportation deferrals to undocumented immigrants who arrived in the U.S. as children.

But the last attempt at broad reform came in 2013, when the Senate’s “Gang of Eight” passed a sweeping bill that died in the Republican-led House.

In the absence of wholesale reform, advocacy groups are pushing for a piecemeal approach, including creating a pathway to citizenship for undocumented workers, raising visa caps on a temporary basis, and better securing the border, in part to win participation from lawmakers focused on illegal immigration.

They’re forming alliances and pressing Congress to make progress on immigration, working to make an economic case on an issue that has become a political third rail.

In the interim, some companies that rely on immigrant labor are taking their own steps to lure workers.

Meat processor Tyson Foods (ticker: TSN), which made headlines early in the pandemic when it was forced to close several plants due to Covid-19 outbreaks, has 120,000 U.S. employees who hail from 160 different countries and speak 50 different languages.

Some are permanently in the U.S., while others are on temporary work visas.

Over the past year, Tyson has spent an additional roughly $500 million on wage increases and bonuses for its front-line workers; the company says its average hourly pay is now more than $18, or $24 including benefits.

But it isn’t just about wages: To increase the availability of workers, the company also helps employees with child-care, housing, and transportation.

It has programs to pay for employees’ education, offers immigration-related legal services, and provides free medical care at its own health centers.

And it holds regular conversations with elected officials on ways to update the country’s immigration system and provide pathways to citizenship.

“Pay and benefits are still at the top of the list, but in my view, they’re table stakes,” says Hector Gonzalez, Tyson’s head of labor and team-member relations. “Employers have to go beyond that.”

But there is a limit to just how much help the company can provide to workers who need things like permanent work authorization that only Congress could provide, says Gonzalez: “We can’t do it alone.”

Nicholas Jasinski contributed reporting to this article.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario