Not Even the Ukraine War Changes the Central Asian Equation

Even if Russia’s influence is weakening in relative terms, Moscow knows it can’t be forsaken.

By: Ekaterina Zolotova

Russia may be losing its grip on Central Asia.

Though the countries of the region are generally thought of as strategic Russian partners – and especially thought of as such by Russia – they have been acting more on their own accord lately in ways that Moscow would rather they not.

The most prominent example is Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s refusal to use the MIR payment system, Russia’s version of SWIFT.

Kazakhstan has also halted Belarusian and Russian trucks at the border, ostensibly for fear of violating Western sanctions.

For years, the foreign policies of Central Asian states were constrained by the strength of Moscow and a lack of alternative partners.

But since the Cold War, they have slowly reclaimed more of their sovereignty.

And now that the war in Ukraine is weakening Russia’s position there, they have an opportunity to reclaim even more.

It’s worth noting the peculiarity of Russian policy toward Central Asia.

In the early part of the 20th century, certain aspects of international affairs such as political economy, law, treaties and so on developed slowly and measuredly under the newly formed Soviet Union.

Most international laws were implemented by capitalist states; the Soviet Union was not a capitalist state and as such had foundational and constitutional inconsistencies with certain international norms.

However, that changed somewhat after World War II as Moscow's geographic reach expanded far beyond its borders.

To reconcile the differences, the Kremlin adopted a dualistic approach to international relations that recognized norms and international treaties with the understanding that international law was meant to manage and regulate relations between two ideologically opposed superpowers.

As important, Moscow operated under the assumption of a fraternal brotherhood among socialist states that presupposed cooperation and assistance.

Put simply, they had an obligation to help each other out.

The Soviet Union may be gone, but this curious approach to foreign policy never really went away.

If anything, it has become more pronounced with the war in Ukraine.

After Russia invaded, it assumed states over which it held influence in Central Asia and the Caucasus would go along with whatever it told them to do.

The Kremlin banked on the idea that cooperation with the West was nothing more than a normal expression of the struggle between the two ideologies of the two powers that need to be regulated.

It wasn’t.

Central Asian countries have far too many priorities now.

They have different ethnic and ethnolinguistic groups, not just Russian Slavs.

Central Asian borders are more artificial than most, so these states have to fight to keep what sovereignty they have, even as different cultural, historic and linguistic groups lay claim to precious resources the state also wants ownership over.

It’s no surprise, then, that Central Asian nations value their (historically recent) independence and sovereignty.

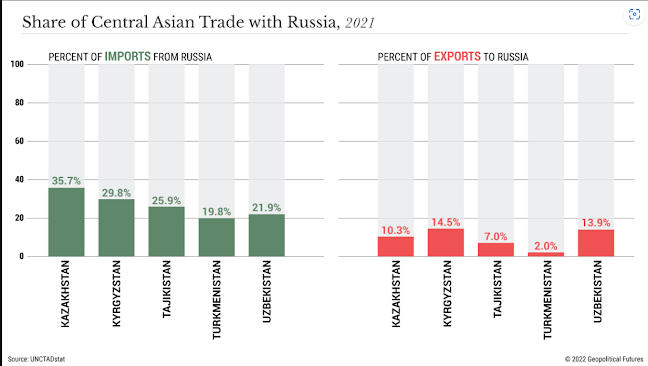

They have never been able to completely forsake Russia, but they are trying to take a more diverse position in world trade, acting independently and increasing investments, opening up more to the world and to international trade, and thus supporting an independent economy.

For them, the key to independence is diversification.

Being Russia’s lackey doesn’t fit the script.

The script looks something like this: If an activity deprives the nation of a benefit or profit, it is dropped immediately.

If it generates the opposite, it is pursued.

It’s a formula based on extreme rational self-interest, not on fraternal ties.

Kazakhstan is a case in point. In light of new Western sanctions (and, indeed, in light of sanctions years ago during the Crimean crisis), many in Russia have criticized Kazakhstan’s behavior as anti-Russian, though nothing it has done signifies the wholesale abandoning of Russia.

In an effort to ensure its sovereignty, several years ago Kazakhstan began to organize language patrols, increasing the spread of the Kazakh language and decreasing the broadcasting of Russian TV channels.

The country's trade has shifted from an exclusively Russian focus to Chinese and global – today there are American, European and Asian companies in the country along with Russian ones.

There are new opportunities for countries of the region to be alternative transport routes and investment destinations.

Moreover, Kazakhstan opposes Russia’s military operations in Ukraine, does not recognize Crimea, and has refused to recognize the results of the referendums in the four Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine.

Still, Kazakhstan remains dependent on Russian trade and investment, and it needs goods such as cheap Russian grain.

Russia’s role in the Collective Security Treaty Organization is also important to Kazakhstan.

It was essential to ending the political protests in Astana in January, and it may prove essential again for snap presidential elections in November.

In other words, Kazakhstan is managing a balancing act, one it hopes will allow it to maintain its sovereignty without participating in the struggle between the two powers.

Kazakhstan understands that the West isn’t especially interested in the region otherwise.

Under the circumstances, then, the country’s decision to avoid secondary Western sanctions is entirely understandable, especially since it hasn’t meant halting all trade with Russia anyway.

In fact, trade ties with Russia are more profitable now as other countries look for alternate ways into the Russian market.

Other Central Asian countries are behaving similarly.

To say that they will turn to Russia when times get tough would be a mistake.

To say they will turn their backs on Russia would be a mistake too.

They need the money relationships with the West often come with, but in Ukraine, they also saw how far Russia would go to protect its interests.

Central Asia can’t afford to alienate either side.

Add to this the fact that Central Asia’s understanding of the world is fundamentally different from Russia’s.

Post-Soviet countries do not believe Soviet-era mindsets will serve their interests.

For its part, Moscow won’t have much incentive to change its ways because Central Asia can’t be free of it, but even so, it seems to have tacitly acknowledged its mistake of assuming they would simply carry its water.

This is why Russia is biding its time, making concessions to the region and standing pat when countries act in ways that don’t benefit Moscow.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario