Investors, Get Used to It: Governments Are Fixing Prices

Plans by Britain’s new Prime Minister Liz Truss to freeze energy bills by borrowing more have downsides, but are probably the best-case scenario for investors

By Jon Sindreu

Britain’s new Prime Minister Liz Truss has all but confirmed that freezing energy bills will be her first big policy move./ PHOTO: NEIL HALL/SHUTTERSTOCK

Britain’s new Prime Minister Liz Truss has all but confirmed that freezing energy bills will be her first big policy move./ PHOTO: NEIL HALL/SHUTTERSTOCKInvestors have spent years unlearning the lessons of Economics 101.

Now, they may even need to accept that price controls have a place in the policy tool kit.

As Liz Truss on Tuesday became the U.K.’s 56th prime minister, she all but confirmed that freezing energy bills will be her first big policy move.

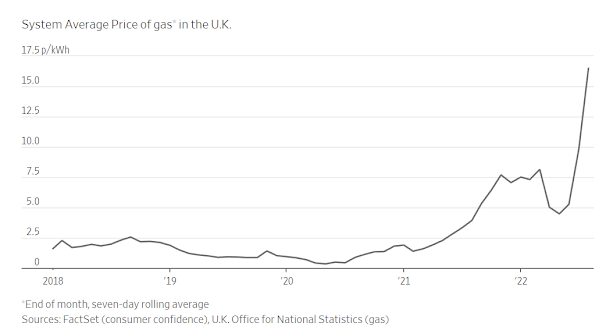

The yearly maximum that British suppliers are allowed to charge households is due to rise to £3,549, equivalent to $4,088, in October—an almost threefold increase from a year ago.

The government’s plans are widely believed to include capping bills at around £2,500 for 18 months and compensating energy firms for their losses.

Since Ms. Truss also has pledged to lower taxes, the money will probably come from borrowing.

Some investors are concerned, because the Bank of England’s policy tightening has already pushed 10-year gilt yields above 3% and the pound trades around its lowest level against the U.S. dollar since 1985.

Most Western nations, including the U.S., have taken steps to offset the surge in commodity prices, including by releasing oil reserves, slashing taxes and sending money directly to households.

Yet Europe’s dependence on Russian natural gas makes it particularly vulnerable, leading to more extreme measures.

European Union leaders are now discussing energy-price caps.

Spain and Portugal have already limited the cost of gas in wholesale auctions, and this week a Spanish minister even suggested intervening in the price of food.

For economists, the key concern is that spending money can’t fix the underlying problem: Freezing the price of a scarce resource dilutes the incentive to buy less of it—in this case risking winter blackouts.

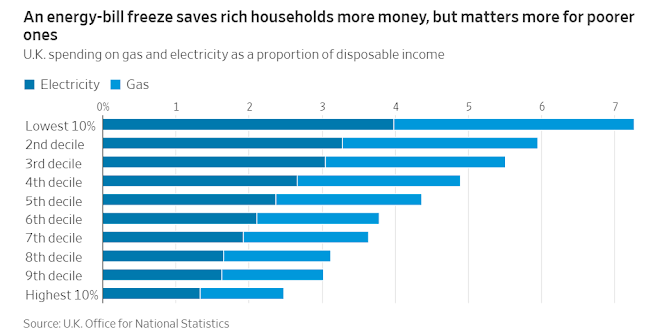

Price caps also end up saving the wealthy more money than the poor.

And the cost is gargantuan: In the U.K., energy-related support measures for families and businesses may total £180 billion, or 8% of gross domestic product, analysts at Deutsche Bank estimate.

But the economic impact of soaring energy bills would likely be worse than the unintended consequences of freezing them.

For one, capping prices is straightforward relative to alternative approaches, such as reforming wholesale power markets.

Meanwhile, the health of the European economy seems hard to decouple from energy bills.

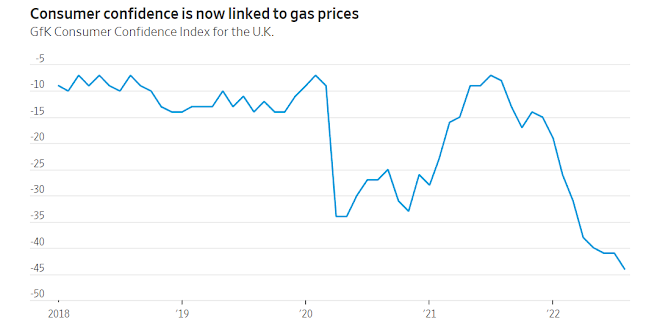

U.K. consumer confidence is at its lowest level on record, despite a robust jobs market.

A recent forecast by Goldman Sachs of U.K. inflation rising above 20% next year was widely circulated in the local media.

Jefferies analysts believe U.K. household gas bills would have topped £4,500 next year, so the expected policy measures would cut them roughly in half relative to current projections.

Crucially, the cost of oft-purchased products such as energy seems to have an outsize hold on the psyche of less-wealthy consumers, which economic research dubs the “frequency hypothesis.”

Because of this, price caps that head off the spike in inflation could limit the hit to consumption across the economy more effectively than spending the same money sending checks to families.

Also, power cannot be easily hoarded, making its price less dangerous to limit than that of food—though caps still need to be deployed alongside strong incentives to contain gas consumption.

As for financing, Ms. Truss’ determination not to tax energy producers that may be profiting excessively from high wholesale prices seems too single-minded, but probably sets a good precedent for investors.

Ultimately, fears about government borrowing remain overblown: Even hawkish central banks won’t let bond prices get too out of whack with interest rates.

Markets don’t react well to scarcity, so investors in Europe face the fallout of soaring commodity prices one way or another.

Price caps may be the least bad option out there.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario