Chairman of Everything"

The Omnipotence of China's Xi Jinping

He has transformed his country into a surveillance state, isolated it from the rest of the world during the pandemic and expanded his foreign policy. Now, China's Xi Jinping is set to become ruler for life. Why is he so beloved by his people?

By Georg Fahrion und Christoph Giesen in Beijing

Xi Jinping is the most powerful man in the world. Illustration: Nigel Buchanan / DER SPIEGELBeijing state television sent a team all the way to the southern Chinese coastal province of Fujian to film a profile of an aspiring young politician.

A chubby-cheeked party member, he was considered at the time, 1993, to be an up-and-coming political talent and he had just recently been named president of the local party school.

His name: Xi Jinping.

The television crew set up their cameras and filmed him frying up some shrimp in a wok.

They then shot an interview with him as his young daughter sat in his lap wearing a pink stocking cap.

In the clip, the crew suddenly starts giggling: "Did she go pee-pee?" a woman asks as she brings over a towel.

"Yes, she went pee-pee," says Xi smiling.

The father’s pants were wet – and it was all caught on camera.

Almost 30 years have passed since then.

The chubby cheeks have remained, but approachability is no longer a characteristic associated with Xi Jinping.

Nothing is left to chance anymore in China.

Today, television images of the head of state and party show him before cheering masses who spring to their feet in unison when he approaches and cheer enthusiastically for minutes at a time.

It is a cult of personality just like the one in neighboring North Korea. Xi is omnipresent.

He is head of state, leader of the party and commander-in-chief of the military - and the ruler of 1.4 billion people. Foto: Xie Huanchi / Xinhua News Agency / picture all

He is head of state, leader of the party and commander-in-chief of the military - and the ruler of 1.4 billion people. Foto: Xie Huanchi / Xinhua News Agency / picture allWhen he opens up the newspaper in the morning, it’s usually his own name that he finds himself reading.

During the 2022 Winter Olympics, the propagandists at the People’s Daily managed to begin each of the 12 headlines on the frontpage with the same three characters: "Xi," "Jin" and "Ping."

Xi Jinping is the most powerful man in the world and the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong.

As head of state, general secretary of the Communist Party and commander-in-chief of the country’s military, Xi occupies all three of the most important offices in the country.

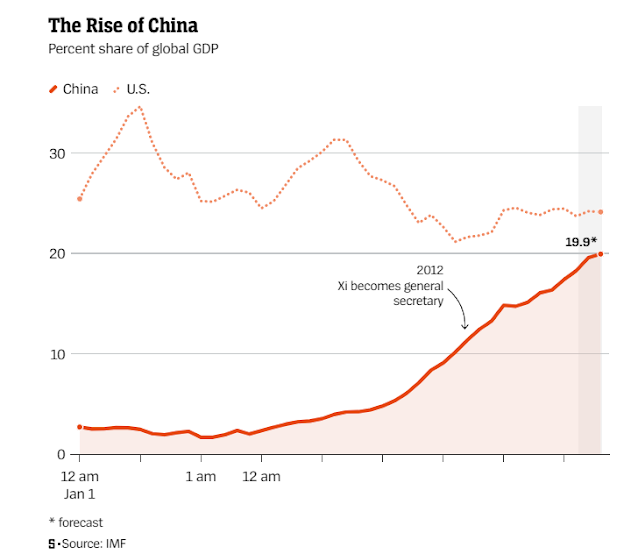

He rules over 1.4 billion people and an economy that will likely soon exceed that of the United States.

Xi exerts control over the most soldiers and the largest navy in the world.

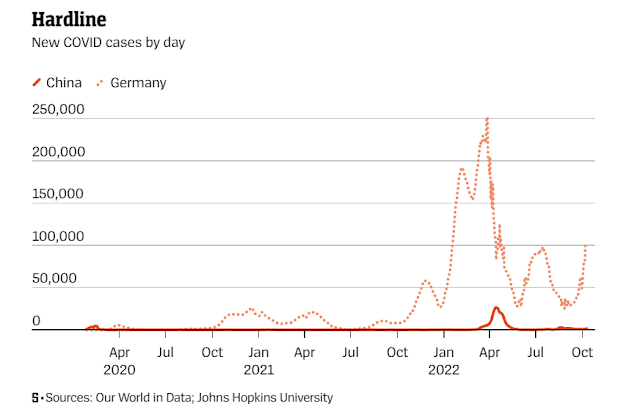

At the wave of a finger, huge metropolises with millions of residents are placed under lockdown, and to implement his zero-COVID policy, the citizens of China are under near total surveillance.

There is no organized political opposition in the country against which he must prove or measure himself.

And his influence extends all the way to Germany.

For companies like Volkswagen or Mercedes, China is the key sales market.

In early November, Olaf Scholz will be traveling to Beijing for the first time as German chancellor, and despite the ongoing debate about the German economy’s unsustainable dependence on China, he will likely bring along a significant delegation of German executives.

Xi’s Communist Party is the cornerstone of the country, a vast institution with 97 million members, far more than the entire population of Germany.

The party leads "the government, the military, civilians the academic; east, west, south, north and center," as it self-confidently proclaims.

And Xi Jinping is the avowed "core" of this party.

His ideology, "Xi Jinping Thought,” has been enshrined in the constitution.

It is a level of power that even Russian President Vladimir Putin can only dream of.

Xi has remained one of the Kremlin ruler’s last friends in the wake of the Ukraine invasion.

On Sunday in Beijing, the 20th Communist Party congress got underway, and if everything goes according to plan, Xi will emerge from the gathering with more power than any Chinese leader has held for decades.

Party leaders are to grant Xi a third term in office, which represents a break with tradition: Following Mao’s death, obstacles had been put in place to prevent a single person from ever again amassing so much power in China.

But when Xi is named head of the party for the third time, it seems unlikely that anyone in China will be able to dethrone him for as long as he lives.

The office of party head in China is more important than the title of president.

And Xi is 69 years old.

He could continue to rule China for decades to come – just like the emperors of old.

The State Council holding a reception to celebrate the 73rd anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China. Foto: Huang Jingwen / Xinhua News Agency / eyevine / laifFor a long time, though, there was nothing to indicate that he would be the one to amass such power, which makes his career all the more remarkable.

Xi was seen as a rather unremarkable party cadre with no clear political profile.

Perhaps that explains why politicians, political scientists, journalists and business executives around the world were hopeful when he took office that he would introduce liberal reforms.

They were yearning for a kind of Chinese Gorbachev.

He turned out to be quite the opposite: a man who has isolated China from the world and pursues revisionist ambitions.

Who, then, is Xi Jinping?

What factors have combined to make him the man he is?

How did he get power, how does he wield it – and what does he now want to do with it?

Summers in the poor inland province of Shaanxi are often so hot that people can only find protection from the heat underground.

In Liangjiahe, a remote village surrounded by sorghum fields, farmers have excavated cave dwellings in the yellow loess cliffs.

Beneath the vaulted arch of one of these caves, it is comfortably cool and it smells earthy.

The ground is trodden down to a smooth floor.

A raised bed made of brick, can be heated by a stove in the winter.

Above the second of the four berths hangs a black-and-white photo showing a man with peach fuzz on his upper lip, his eyes looking into the middle distance.

It's Xi Jinping.

A portrait of Xi Jinping hanging in the cave dwelling where he once lived in the village of Liangjiahe. Foto: Bloomberg / Getty Images

A portrait of Xi Jinping hanging in the cave dwelling where he once lived in the village of Liangjiahe. Foto: Bloomberg / Getty ImagesThis is where China’s current president spent his youth, without electricity or running water.

That period – from 1969 to 1975 – left its mark on him.

When he arrived in Liangjiahe as a 15-year-old, "I was perplexed and lost," he wrote in his autobiographical essay "Son of the Yellow Earth."

"When I left at 22, I had firmly established my life's purpose and I was full of confidence."

His time there, Xi wrote, "planted a firm belief in me: to do practical things for the people."

Such pronouncements, of course, serve a clear propagandistic purpose.

But they have also become a key element of the image that China has developed of Xi.

In that narrative, he appears as someone who has "eaten bitterness," as the Chinese say, meaning he is familiar with the lives of the poor.

It is on the strength of this legend that much of his political success has been built.

It is also true that his father, Xi Zhongxun, was an early revolutionary and counts among the Communist Party’s Eight Immortals.

That makes Xi a so-called princeling, a scion of China’s red nobility.

He was born into the insulated quarters of the party elite in Beijing, where he grew up with his siblings.

Their parents raised the children in an authoritarian manner.

It was a privileged childhood, but one that came to a sudden end when his father fell into disfavor in 1962 after he authorized the publication of a book that Mao found to be inappropriate.

Xi Zhongxun was relieved of all of his posts and forced to go to work in a tractor factory.

And it got even worse for him during the Cultural Revolution, launched in 1966.

Members of the Red Guards abducted and humiliated Xi Zhongxun.

He was locked in prison, and later spent years in confinement in Beijing.

The Xi family, with father Xi Zhongxun in a wheelchair. Foto: Xinhua / eyevine / Xinhua News Agency / eyevine / d

The Xi family, with father Xi Zhongxun in a wheelchair. Foto: Xinhua / eyevine / Xinhua News Agency / eyevine / dHis family was also persecuted. A half-sister to Xi Jinping lost her life, likely through suicide. Like millions of other youth, Xi Jinping was banished to the countryside to learn from the farmers – which is how he ended up in Liangjiahe, the village with the cave dwellings.

It has since been developed into a kind of open-air museum, with former village residents having been relocated to newly constructed residential buildings down in the valley.

To shelter from the August sun, a group of schoolchildren has sat down in the shade of the village sports field as the teacher says: "Did you already know how much Xi Jinping loves to read?

He arrived here with a box full of books." In the small blacksmith’s shop that Xi allegedly helped set up, a man is making soup ladles as souvenirs for the tourists.

A mural shows Xi giving instructions to the farmers.

In the village, gardeners are growing eggplants and chilis and the zinnias are blooming.

In one of the caves where Xi lived back then, a party delegation from Tibet is marveling at the collection of books that he allegedly read: Marx and Engels, Tolstoy, Hemingway, Sun Tzu.

On the wall hangs a framed copy of the certificate documenting his admission to the party, dated January 10, 1974.

He had to apply for membership 10 times before he was finally accepted, with party officials hesitating to take on the son of an outcast.

That same year, Xi became party secretary of Liangjiahe, the first rung of the career ladder for the future politician.

Why, though, did Xi decide to devote his life to the party that had ripped apart his family and plunged it into suffering?

He had all the reason in the world to hate the party.

"The way Xi Jinping himself tells the story, he believes in the party so much precisely because his faith in communism was shaken," says Joseph Torigian, who teaches at the American University in Washington and has written a biography of Xi’s father.

A lost and then rediscovered faith is stronger than anything else, Xi is reported to have once said.

He became "redder than the red" in order to survive, a former friend of his told an American diplomat, according to a dispatch published in 2009 by the whistleblowing platform WikiLeaks.

"The lesson he seems to have learned from the Cultural Revolution is not that you have to limit the Party," says Torigian, "but that you have to prevent a situation from getting out of control."

This approach is fundamentally different than the one taken by Mao, with whom Xi is often compared because of the amount of power he has amassed.

Whereas Mao at times ruled through chaos, Xi wants stability and order at all costs.

State founder Mao greeting soldiers from the People's Liberation Army Foto: Heritage Images / Heritage Images / ullstein bild

State founder Mao greeting soldiers from the People's Liberation Army Foto: Heritage Images / Heritage Images / ullstein bildXi’s maxims could be summed up as follows: Whereas party cadres owe the people honest work, the Chinese people, in exchange, owe allegiance to the party.

Under Xi, freedoms have been drastically curtailed, with society becoming much more uniform.

He is intent on driving out a disposition among Chinese that tends toward anarchism and is frequently described with the phrase "cha bu duo," which can be translated as: "Close enough."

Cha bu duo describes a culturally rooted laxness that makes China so livable: The last bit of effort isn’t absolutely necessary, it’s too onerous.

We don’t have to be perfectly precise, there’s no real need.

You bought the wrong ticket?

The conductor will turn a blind eye.

One green sock and one red sock?

No big deal. Cha bu duo means that a detour is always available if the path ahead is blocked.

Xi, it would seem, can’t stand it.

Under his leadership, draconian laws and decrees have been issued that have drawn the societal corset tighter and tighter.

The new national intelligence law, for example, which can essentially force every Chinese citizen to become a spy.

Or the particularly ambiguously worded security law, which defines almost any activity at all as a potential threat to national security.

According to the law, China is now being defended in cyberspace, outer space, at the bottom of the ocean and in the polar regions.

A country that is ever watchful.

No more cha bu duo.

This fixation on security is perhaps most brutally apparent in Xinjiang, homeland of the Uighurs.

Until 2014, when Xi traveled to the region, officials had primarily focused on economic development to pacify the ethnic conflicts that erupted repeatedly.

But Xi prescribed an "ideological cure" for the Muslims of Xinjiang and demanded that the Communist Party show "no mercy."

The hardliner Chen Quanguo, who was sent to Xinjiang to lead the party there, quickly established a police state that has no equal in the world today. Hundreds of thousands of people were locked away in reeducation camps.

A Uighur protest in 2009 in Ürümqi, the capital city of the Xinjiang region. Foto: Oliver Weiken/ DPA

A Uighur protest in 2009 in Ürümqi, the capital city of the Xinjiang region. Foto: Oliver Weiken/ DPAXi’s goal was the harmonious coexistence of China’s ethnicities like "the seeds of a pomegranate" – enveloped within the red shell of the party.

He wants to transform the Muslims of Xinjiang into obedient, docile children of the party, working for the nation’s purpose without a thought for any other ideology than his own – and certainly not for Islam.

The Hong Kong democracy movement has encountered a similar mercilessness, if not the same level of brutality, in the last three years.

The city, with its rejection of the party’s authority and desire to retain control of its own political fate, was likely seen by Xi as a provocation.

He broke Hong Kong’s resistance by forcing a new national security law upon it in 2020.

Since then, freedoms have been massively curtailed and opposition activists are either in prison, have left the country or no longer dare to speak out.

The degree to which Xi has changed China shouldn’t come as a complete surprise, since he laid out his vision for the country early on.

Just a few months after he took office, Chinese journalist Gao Yu leaked Document Number Nine, for which she was sentenced to five years in prison.

In the memo, sent to all important Communist Party officials, party leaders warned against ideas with which "anti-Chinese forces from the West" were seeking to infiltrate the country.

China, the document states, must resist ideas such as "universal values," "civil society" and "the Western conception of journalism" with all its might, since they weaken the party’s primacy in the political landscape.

Document Number Nine was essentially Xi’s roadmap.

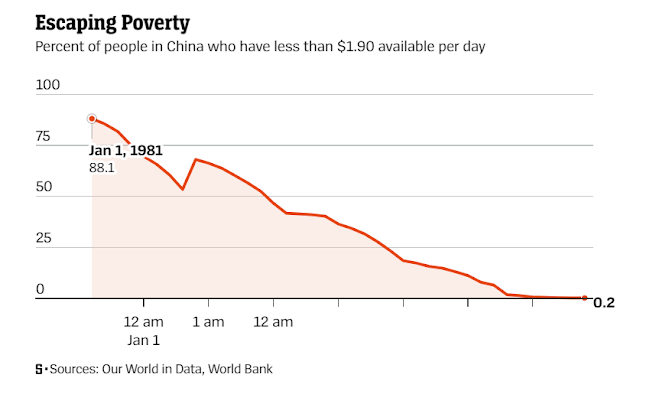

Those who fall into line – and this is the flipside of the Chinese dystopia – can expect a comfortable life and are provided with better government services than any preceding generation.

In that sense, Xi is a convinced socialist; he focuses his policies on those who have less.

One of his priorities was combatting rural poverty, and in 2021, he proudly declared that he had won that battle.

His new economic campaign, announced in 2021, is focused on the growing middle class and is called "Common Prosperity."

It envisions greater redistribution combined with stronger worker rights and affordable rents.

For large internet companies and their super-wealthy founders, by contrast, a more challenging age has dawned.

To help fund Xi’s campaign, they donated billions – allegedly voluntarily.

Xi Jinping's career got going after the end of the Cultural Revolution – with the help of his father, who had been rehabilitated by that point.

Early on, Xi gained a reputation as a politician clean of corruption.

In 1985, the party sent him to Fujian, one of the provinces in which China’s economic miracle got its start.

During the reform era, with its dizzyingly high growth rates, those with ideas, chutzpah and connections – and with a nose for bribing the right people – could become fantastically wealthy.

In 1999, a vast network of corruption was unearthed in the province in which a single businessman had bribed more than 300 officials.

One of the few who managed to emerge from this morass unsullied was Xi Jinping.

The leadership in Beijing summoned him – he had risen to become governor of Fujian by then – to deliver a report on the mess but they left him in office.

"We will remove corrupt elements without mercy," he promised at the time.

In the WikiLeaks cable from 2009, his former friend reports that Xi was "repulsed by the all-encompassing commercialization of Chinese society, with its attendant nouveau riche, official corruption, loss of values, dignity, and self-respect."

Beyond that, though, Xi remained a political enigma.

"He got along with the leftists in the Party as well as the rightists," says Joseph Torigian, his father’s biographer.

In China’s authoritarian system, it seems advisable for many people to hide their views, but Xi Jinping was particularly good at it, he says.

"Those who met him left feeling that Xi was positive about them – but also that he never let on what he really thought."

Snow covered the mountains of Switzerland when Xi Jinping began his speech at the annual general assembly of capitalism in 2017.

It was the first time a Chinese head of state had ever traveled to the World Economic Forum in Davos, and his visit came at a critical juncture: It was January 17, three days before the America First protectionist Donald Trump was to be sworn in as U.S. president.

The future of globalization suddenly looked murky indeed.

The most powerful communist in the world spoke in the Davos Congress Centre before 1,200 guests.

"Pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room," Xi intoned.

"No one will emerge as a winner in a trade war."

He expressed his commitment to "economic globalization" and condemned the stubborn pursuit of one’s own interests.

"China will keep its door wide open," he pledged.

It seemed that Xi was saying everything that the global elite wanted to hear.

More than that, he delivered the speech that they had really been hoping to hear from a U.S. president.

With Trump holding a knife to the throat of the old world order, Xi suddenly looked like its guarantor.

U.S. President Donald Trump and Xi Jinping with their wives in 2017 in the Forbidden City of Beijing. Foto: Jonathan Ernst / REUTERS

U.S. President Donald Trump and Xi Jinping with their wives in 2017 in the Forbidden City of Beijing. Foto: Jonathan Ernst / REUTERSWhat a colossal misunderstanding.

The speech is an example of how the West, in its interpretation of China, has allowed itself to be misled by its own hopes and aspirations because it has an insufficient understanding of the Chinese discourse.

"What Xi had in the back of his head in Davos wasn’t a further opening of China, but preventing the West from closing itself off to China,” says sinologist Marina Rudyak, who teaches at the University of Heidelberg.

Xi, she says, wasn’t trying to do a favor to American capitalists.

Rather, he was trying to remove hurdles standing in the way of his historic mission.

Perhaps Xi Jinping’s greatest talent is that of telling stories, says Kerry Brown, a former British diplomat and the author of a Xi biography.

"His style of politics, and the messages underlying it, appeals to the emotions and aspirations of many Chinese."

Xi propagates a rejuvenated country that is finally leaving its disastrous recent history behind. Xi is constantly speaking of "fuxing,” the "rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

From the middle of the 19th century to the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, colonial powers divided up China into spheres of influence, fleecing the country of its riches and plunging it into a series of wars.

Even today, the Chinese refer to it as the "century of humiliation,” and every child learns about it in school.

No country would find it easy to move beyond such an ignominy, but it has proven especially difficult for China, a land with thousands of years of cultural tradition that has customarily seen itself as the center of the world.

Getting the country back on its feet and returning it to greatness has been the goal of pretty much all political movements in China in modern times.

It had already been Mao's quest to make China great again.

Xi, though, is leading the People’s Republic at a moment in time when this vision is no longer a theoretical ambition on the distant horizon, but seems imminently achievable.

Which goes a long way toward explaining Xi’s course.

Disciplining the party and society, the commitment to ideology, solidifying his own power – all of that serves this greater goal.

"This is a new historic juncture in China’s development," Xi said at the 19th party congress five years ago, just a few months after his appearance in Davos.

"The Chinese nation … has stood up, grown rich, and become strong – and it now embraces the brilliant prospects of rejuvenation." China, he said, was entering a "new era."

The path, Xi warned, won’t be easy.

"It will take more than drum beating and gong clanging to get there."

Under Xi, China has begun pushing its foreign policy interests far more ruthlessly than it used to.

"The East is rising, and the West is declining, there's not a doubt in their thinking," says Christopher Johnson, former chief China analyst for the CIA.

But in order to take over the lead in the global pecking order, China has to move ahead of the U.S.

"They have judged that the U.S. is their implacable enemy," Johnson says.

From Beijing’s perspective, the U.S. is standing in the way of history because it allegedly begrudges China its rise.

That helps explain why Beijing reacts so excessively when Washington ratchets up its support for Taiwan.

How can the nation’s rejuvenation be completed without bringing Taiwan back into the fold, which, from China’s point of view, was torn from the motherland in 1895 by imperialistic Japan and has been ruled by counterrevolutionaries since 1945?

Xi has made clear that the reunification of Taiwan with the mainland cannot simply be pushed off from generation to generation.

Besides, it would secure him his place in the history books.

U.S. President Joe Biden holding a video meeting with Xi in 2021. Foto: Sarah Silbiger / CNP / Polaris / laif

U.S. President Joe Biden holding a video meeting with Xi in 2021. Foto: Sarah Silbiger / CNP / Polaris / laifIn the dispute with the U.S., Xi’s China is prepared to use almost any means necessary.

His propaganda oozes with anti-Americanism while "wolf warrior" diplomats spread disinformation, such as the myth that the September 11 terrorist attacks were an inside job. Beijing blasts disagreeable allies of the United States, such as Australia, with sanctions, which of course cannot be called sanctions so that China can continue to express anger at the punitive measures Washington has taken against Russia – a partner whose violations of international law China ignores because Russian President Vladimir Putin has identified the same primary enemy.

That also explains why Xi has remained at Putin’s side despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine:

Although Xi has, to be sure, indicated that he has his doubts about Putin’s campaign, in China itself, it is the West that is exclusively blamed for the war.

Xi is fighting for global supremacy and Putin is merely a junior partner in that effort – who happens to have numerous nuclear weapons and can supply energy.

Putin may still be useful, which is why Xi hasn't discarded him.

Russian President Vladimir Putin met with Xi in Samarkand, Uzbekistan in September. Foto: Sergei Bobylev / TASS / picture alliance / dpa

Russian President Vladimir Putin met with Xi in Samarkand, Uzbekistan in September. Foto: Sergei Bobylev / TASS / picture alliance / dpaChina doesn’t even shy away from the mafia playbook. In order to force Canada to back down in a dispute centered on the detention of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, Beijing held two Canadian citizens hostage for almost 1,000 days.

But Xi’s quiver also includes less belligerent methods for projecting power.

Earlier this month, China was able to prevent a debate in the UN Human Rights Council over the suffering of the Uighurs in Xinjiang.

Seventeen members of the council voted in favor of holding the debate, but China was able to organize 19 dissenting votes.

They came from fellow socialist countries like Cuba and from business partners like Qatar – but also from places like Pakistan and Indonesia, over which China has gained influence through its Belt and Road Initiative.

Taken together, Xi’s activities have had a disastrous effect on China’s reputation in Europe and the U.S., with fewer and fewer people having a positive view of the country.

In a recent survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, 76 percent of respondents from 19 mostly Western countries said they have no or not too much confidence that Xi would "do the right thing regarding world affairs."

Many German companies are taking a critical look at their dependence on China, especially since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Undoing the economic knots that tie the German economy to China would likely be far more expensive and complicated than doing without Russian oil and natural gas.

German Chancellor Scholz warned recently against a "de-coupling" from China.

Former German Chancellor Angela Merkel with Xi in China in 2019. Foto: Michael Kappeler / picture alliance / dpa

Former German Chancellor Angela Merkel with Xi in China in 2019. Foto: Michael Kappeler / picture alliance / dpaBut even as China’s image has plunged in the West, things look quite a bit different back home.

According to a survey published by the communications firm Edelman in January 2022, 91 percent of the Chinese have trust in their leadership, "the highest seen in a decade."

The reason: For the last four decades, many Chinese have seen their material well-being improve from year to year.

The world is again taking China seriously – and is even frightened by it.

That is something that resonates with many Chinese.

And it tends to only be those who fall afoul of the system who realize just how rigid it has become.

"When they read my name in foreign media, the police will immediately knock on my door," says Li Datong.

The 70-year-old continues to speak out nonetheless.

He has been seen as a trouble-maker ever since 2006, when he was the editor-in-chief of a party publication and chose to print an untoward article, whereupon he lost his job.

His deep insights into China’s power structures, though, don’t just come from his former job.

Like Xi, Li is a Communist Party princeling: His father was once the head of propaganda.

Today, Li is one of the few people left in China who dares to express divergent viewpoints, to a degree protected by his family background, but politically marginalized.

In his dark apartment on the outskirts of Beijing, Li complains about the authoritarian path the country is on and about the yes-men he says surround certain members of the leadership.

Li is not particularly diplomatic and has a clear affinity for cursing.

But, Li says, "I know where the red line is.

I cannot be calling his name."

This is how far Xi has come since he advanced to the party leadership position in the autumn of 2012. Initially, he was seen as a compromise candidate.

"Neither the Shanghai gang nor the Communist Youth League, the most powerful factions at the time, were able to get their candidates through," says Richard McGregor, the author of an authoritative book about the Chinese Communist Party.

"There was no sign that he would develop into what he is today."

Xi took over control of a floundering organization.

It was unsure about its sense of purpose, rife with corruption and losing authority.

It seemed to no longer have firm control of the country.

There was corruption wherever you looked. Near the ministries in Beijing, shops had popped up selling Swiss watches, exclusive aged whiskey and expensive perfumes – as gifts for government officials.

Part of the business models of these shops was to accept the gifts back later in exchange.

"Xi Jinping adroitly took advantage of the sense of crisis that was gripping all of the top leaders at that time," says Christopher Johnson, the former CIA analyst.

"Xi is very good at transforming a crisis into his advantage," says Richard McGregor.

His greatest rival at the time was Bo Xilai, head of the party in Chongqing.

All of China was talking about him.

He was widely seen as a man with solid morals and communist values, a neo-Maoist who would lead the party back to its roots.

And he was incomparably more charismatic than the designated party head Xi.

It was seen as essentially a foregone conclusion that Bo would become a member of the Politburo Standing Committee at the 2012 party congress, a position that would have enabled him to stymie Xi.

But then came November 13, 2011, when Bo’s wife Gu Kailai poisoned the British national Neil Heywood in a three-star hotel in Chongqing.

The murder was covered up – until the city’s police chief, Bo’s right-hand man, fled to the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu in February 2012.

There, he told the American diplomats everything: Heywood had helped the Bo clan move money abroad – despite all of their blatantly flaunted devotion to communism – and sought to blackmail the family with what he knew.

Xi demanded a harsh response and got his way.

Bo and his wife ended up in prison.

Xi’s greatest rival had been neutralized.

Xi then copied the red campaign that Bo had prescribed Chongqing and later rolled it out across the entire country, a campaign focused on more nationalism and more ideology.

Bo Xilai, formerly Xi's most dangerous rival, at his 2013 trial in Jinan. He was sentenced to life in prison. Foto: Xie Huanchi / Xinhua News Agency / eyevine / laif

Bo Xilai, formerly Xi's most dangerous rival, at his 2013 trial in Jinan. He was sentenced to life in prison. Foto: Xie Huanchi / Xinhua News Agency / eyevine / laifXi had hardly entered office when he issued comprehensive measures aimed at fighting corruption.

From December 2012 to June 2021, the party's Central Commission for Discipline Inspection didn’t just investigate 631,000 lower-ranking members of the party – referred to derisively by Xi as "flies" – but 393 powerful party leaders, called "tigers," also lost their jobs.

Many of them ended up in prison.

There was also fabulous wealth to be found in the immediate surroundings of the president himself.

In 2012, the Bloomberg news agency published a report according to which Xi’s extended family had amassed several hundred million dollars through company investments and real estate deals.

The largest share of the riches was attributed to his brother-in-law.

In 2015, the New York Times took the story further, reporting that relatives of Xi’s had invested early on in a company belonging to the country’s wealthiest man and later sold their shares for a multimillion-dollar profit.

However, Xi himself has never been implicated in such deals, nor have his wife or daughter.

For Xi, the anti-corruption campaign had two significant advantages: It increased his popularity in the country, with people no longer having to bring along a bottle of perfume or whiskey every time they interacted with public officials.

And it enabled Xi to get rid of his political adversaries.

Powerful functionaries fell victim to the purge, such as Zhou Yongkang, former head of the security services, in 2013.

In 2017, it was the turn of Sun Zhengcai, a member of the Politburo who many had seen as a potential successor to Xi.

Both were sentenced to life in prison.

Since then, all power in China has been concentrated in Xi’s hands.

Whether it is economic or financial questions, it is all taken care of by Xi’s people, the "Xiites."

He even gets involved in the details. In 2014, for example, he personally issued 17 decrees relating to environmental protection.

And if any of his directives isn’t followed to the letter, the offender faces an abrupt end to their career.

Under his pre-predecessor Jiang Zemin, the Standing Committee made its decisions by majority vote.

Then came Hu Jintao, who even gave a veto to every member of the committee, referred to at the time as "the nine dragons controlling the water."

Xi’s nickname, by contrast, is "chairman of everything."

At one time, Article 79 of the Chinese constitution held that the president was not allowed to hold onto power for longer than two consecutive terms. In 2018, Xi had the provision removed, to the delight of party newspapers.

But not all Chinese were equally convinced.

Was this not an example of a modern-day ruler claiming the ancient "mandate of heaven" so he could stay in office for life?

On the day of the announcement of the elimination of term limits, internet censors in China blocked the hashtag #Emperor within minutes.

Developments on the stock exchange, though, were extraordinary: Shares for the company Shenzhen Emperor Technology rose by almost 10 percent.

It was a way for stock investors to draw public attention to the term despite internet censorship – a creative form of protest that is understood in China.

When Xi entered office in 2012, the Chinese internet was a wild, chaotic place where the armies of censors frequently found themselves trailing hopelessly behind clever users.

Today, artificial intelligence takes care of most of the thought-control police work.

The "Great Firewall," which separates China’s internet from the rest of the world, has become almost impermeable.

The government has criminalized the use of VPN software, which can help users avoid such cyber-impediments.

But what began with the internet has now grown to encompass the entire country: Complete control, everywhere.

On a day in August 2022, men in white, full-body suits push a container on wheels through the airport in the southern Chinese city of Haikou.

Through the windows of the negative pressure box, a man can be seen, his gaze lowered – an airplane passenger who wasn’t allowed to board because the COVID app on his phone had turned red.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that he is infected; he may just have walked through a city district where a couple of infected people live.

But he is being taken into quarantine anyway.

Just part of life in zero-COVID China.

The battle against the pandemic is becoming increasingly frantic in China.

Officials have flown drones through locked-down cities to remind residents to "control your soul’s urge for freedom."

They have separated infected parents from their babies and prevented mothers about to give birth from entering hospital without a COVID test.

Almost three years after the start of the pandemic, China remains isolated from the rest of the world.

Scott Kennedy from the Center for Strategic and International Studies has been traveling to China for 30 years, and finally was able to make his most recent trip in September – likely as the first senior American political analyst since the start of the pandemic.

"I think the people are hungry for exchange," Kennedy says in summarizing his conversations with academics, businesspeople and officials in Beijing.

He says his interlocuters treated him courteously, but he still sensed an estrangement that he found unnerving.

"We've always been 12 time zones apart," he says, "but now it feels like we're on different planets."

Day after day, state media outlets continue to crow that under Xi’s leadership, China has managed to keep the virus at bay, and that this achievement proves the superiority of China’s system over those of other countries that haven’t fared as well – basically all of them, but especially the U.S.

Whereas America is beset by decadence and chaos and has seen a million victims, China is an oasis of order and safety.

The People’s Republic as best in the world, with Xi fulfilling his promises – such is the narrative.

Why would he ever even consider changing course?

In reality though, as the rest of the world is learning to live with the virus, it continues to impair life in China.

The series of lockdowns shows no sign of ending – in Xi’an, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Chengdu, Guangzhou and on the holiday island of Hainan – and the fight against the highly infectious Omicron variant is looking increasingly futile.

On top of that, it is a risky strategy.

The greater the number of those who suffer from lockdown trauma, who have had to give up their businesses or are having trouble finding jobs, the greater the frustration.

In the second quarter, Shanghai’s economic output collapsed by 14 percent, with the 5.5 percent growth targeted by Premier Li Keqiang for 2022 almost certainly unreachable.

And if the country’s leadership continues to require most of the population to take a PCR test every few days, that alone will consume more than 7 percent of public revenues.

"Chinese elite politics were pretty opaque before," says Kennedy.

"By now, they have sealed any light." The China of today is a different country than it was with Xi came into power.

He has subjugated the system to himself, and the principle of collective leadership is history.

"People in the West think that is a retrogression," says Victor Gao, vice president of the Beijing think tank Center for China and Globalization.

He was once the interpreter for the reformist leader Deng Xiaoping, today he is essentially responsible for explaining the party to the outside world.

Gao says he thinks that China needs a strong leader at the top in this moment of history.

"Xi will consolidate his grip on the party and the military and enhance his control over the country," he says.

But Xi Jinping’s greatest dilemma – his "principal contradiction," to borrow from Marx – remains: Zero COVID and acceptable economic growth rates cannot be had simultaneously.

And that is true despite the government mouthpieces People’s Daily and Xinhua publishing three articles in two days claiming that zero-COVID is the only acceptable approach.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario