Banks Could Get Nudged Out of Leveraged Lending

The trouble with a recent deal for buyout debt could be an even bigger worry if more of that type of lending shifts away from banks

By Telis Demos

Many banks, such as Bank of America, have made markdowns to their deal-financing books in the second quarter. / PHOTO: MIKE BLAKE/REUTERS

Many banks, such as Bank of America, have made markdowns to their deal-financing books in the second quarter. / PHOTO: MIKE BLAKE/REUTERSWall Street banks finally moved a big slug of buyout debt recently, but investors shouldn’t get hung up on it.

What they should be worried about is banks not doing enough deals.

Investment banks across Wall Street including Bank of America, BAC -2.37%▼ Credit Suisse CS -12.10%▼ and Goldman Sachs GS -3.50%▼ are on track to share losses of more than half a billion dollars in the financing for a leveraged-buyout of Citrix Systems, CTXS -0.06%▼ The Wall Street Journal has reported.

After delaying the offering until last week, they were able to sell bonds and loans sitting on their books, but at steep discounts.

Pinpointing how that will hit any individual bank is hard, but the experience could affect future deals.

Many banks have already made markdowns to their deal-financing books in the second quarter.

Bank of America marked down debt in this category by around $300 million, JPMorgan Chase JPM -1.86%▼ had markdowns of about $250 million on its book of so-called bridge loans and others also made adjustments.

Unless there are further waves of markdowns, it isn’t likely to make a huge dent in third-quarter earnings overall—especially when investment-banking revenues are already so depressed.

But leveraged lending is often a key cog in investment-banking machines.

These deals help generate merger-and-acquisition fees and trading revenue and set banks up for roles in future deals by the players involved.

So as painful as losing on a particular transaction might be, banks will hope they will still get the call for the next one.

If they don’t, someone else might, and that someone else could be the vast and growing private credit market.

Deals the size of Citrix, with a $15 billion debt package, for now might be ones that only banks can handle.

But private credit has been climbing up the food chain.

Some sizable recent deals, such as for Avalara and Zendesk, have been supported by private credit, and firms such as Blackstone or Blue Owl Capital can write increasingly big checks directly to borrowers, bypassing the need for a bank to parcel out the debt.

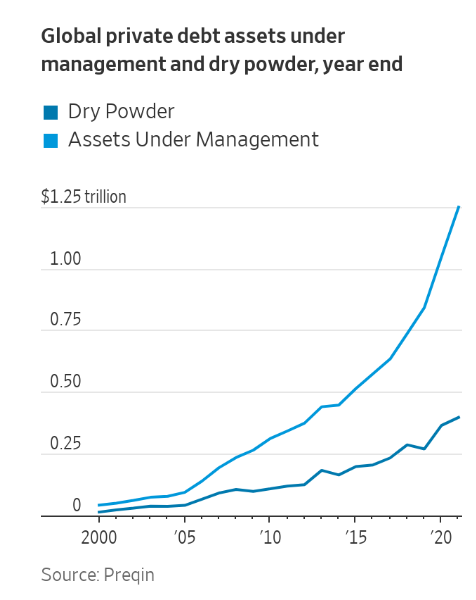

Private debt funds had some $1.25 trillion in assets under management globally as of the end of last year, up nearly 50% from the end of 2019, according to Preqin.

About $400 billion of that was dry powder, or undeployed capital.

The giant California Public Employees’ Retirement System is adding a new allocation for private credit.

Equity analysts at Goldman Sachs in a recent note counted “banks pulling back,” and the more challenging environment leading to better terms for lenders as positive indicators for the outlook for private-credit providers.

Private credit can offer certainty of execution that banks often can’t match since they ultimately need to pass the debt on to other buyers.

Private credit firms also might require some other tough terms in exchange, but those might be worth the cost in a difficult market.

Meanwhile, big banks are now often trying to limit their exposures to some categories of lending, in part as a way to restrain the growth of their risk-weighted assets and lower the pressure to build up capital.

Their caution might pay off if losses move from ones based on market moves to credit deterioration.

Private credit funds that hold loans that are less-sensitive to price changes still would suffer from credit losses.

Yet if the economy manages to skirt through the Fed’s hawkish cycle and defaults are manageable, that might only embolden private credit to encroach even further on banks’ turf.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario