Habeck's Meltdown

Nuclear Energy Standby Proposal Has Germany's Greens Seeing Red

German Economy Minister Robert Habeck was on the verge of becoming a political superstar. But now, the Green Party heavyweight may be experiencing a meltdown in the face of the country's looming energy shortages – and his proposal to use nuclear power to bridge the gap if worse comes to worst.

By Marina Kormbaki, Benedikt Müller-Arnold, Jonas Schaible, Christoph Schult und Gerald Traufetter

Just to ensure that the business-friendly Free Democrats didn’t think he was asking too much of them, German Economy Minister Robert Habeck took pains to signal that he was actually putting his own party, the Greens, to the test.

That, after all, is what one must do in coalition governments.

On Monday, after explaining to lawmakers from his own party that he wanted to keep two nuclear plants on standby this winter to deal with possible energy shortages, he walked down the hall of the Reichstag – home of Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag – to address a meeting of FDP parliamentarians.

Even though his Green Party has been in a coalition with the FDP and the Social Democrats (SPD) since last December, it marked Habeck’s first visit to the FDP parliamentary group.

But there was no way around it.

Participants say that he started by telling the liberals that he had just addressed his own party.

"You can imagine," he said, "that my proposal didn’t trigger an outpouring of enthusiasm."

That, though, wasn’t totally true.

The Greens had actually steeled themselves for worse.

Many party members, to be sure, would prefer Habeck to simply shut down Germany’s three remaining nuclear plants by the end of the year, as planned.

But within the FDP, many lawmakers agree with the conservative opposition that the reactors should continue operating – until spring 2024, for example – to address Germany’s looming energy crisis.

Habeck has proposed a compromise, calling for two of the three reactors to be kept in working order on standby, though not actively running, until mid-April as an emergency backup.

An idea that has a little something for the FDP and a little something for the Greens.

It's the kind of compromise that democracies are made of, but such an approach needs to be skillfully handled – and that is one box that Habeck didn’t check.

He had hardly announced his plan before nuclear power plant operators sent a letter informing him that it wasn’t technically feasible.

Accusations were made and concerns were voiced, both within the FDP and the Green parties.

And suddenly, doubts have developed as to whether Habeck is up to the job of guiding Germany’s economy at a time when the country is facing a possible recession and potential power shortages.

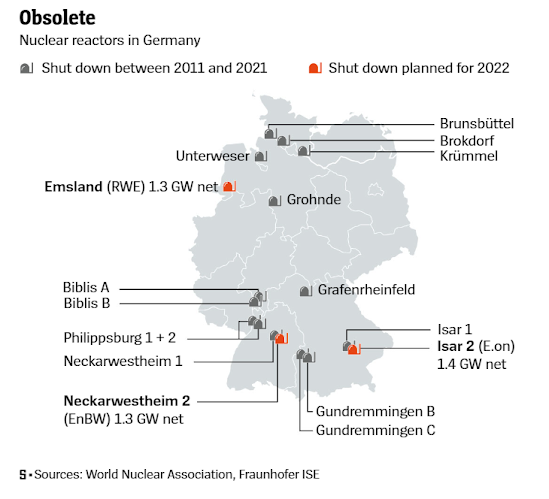

Just this spring, it still looked as though Germany was going to complete its phaseout of nuclear energy as planned.

When the first demands emerged following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to allow the country’s remaining nuclear reactors to stay online, Habeck and Environment Minister Steffi Lemke, also of the Greens, ordered that the facilities undergo an initial stress test.

The four operators of Germany’s power grid performed an analysis to determine whether energy supplies in the country were in danger because of the war.

And they concluded that there was no danger.

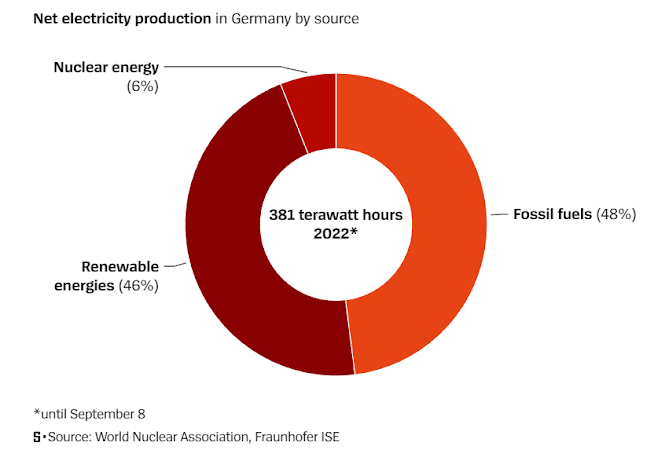

See, the Greens said, Germany is facing a heating problem, not an electricity problem – and nuclear facilities don’t produce useable heat, only electricity.

But the debate didn’t end there.

Leaders in industry and in the political opposition began asking: If every kilowatt-hour saved was beneficial, then isn’t it true that every kilowatt-hour produced is important as well, even if they are produced by nuclear power plants?

It was a question that put the Greens in something of a tough spot.

They responded by pointing out that nuclear energy remains extremely risky, with every reactor akin to a ticking timebomb.

Eleven years ago, following the nuclear accident in Fukushima, a majority of German voters agreed.

But the Russian invasion of Ukraine has changed the equation .

Climate change is also doing its part to make nuclear power more acceptable to many.

The drought in Europe has hampered the production of hydroelectric power and made it more difficult to transport coal by ship, though the water-cooling of nuclear reactors has also grown more challenging.

In the conservative opposition, a number of important voices eagerly sought to back the Greens against the wall on the issue.

It was easy to produce headlines with demands to extend the lifespans of the country’s remaining nuclear facilities.

In summer, the pressure on Habeck began to increase.

If he refused to budge, he and his party would be blamed for any electricity and heating shortage that might materialize this winter.

Growing Pressure

And as the pressure from his political opponents and from reality began to grow more intense, an idea began to take shape.

Numerous interviews during the summer indicate that Habeck ultimately concluded that he wasn’t interested in risking electricity shortages.

And that extending operations at a reduced production level using old fuel rods was less potentially disastrous than a winter blackout.

Habeck passes Greenpeace activists as he heads into a press conference on Monday of this week. Foto: JOHN MACDOUGALL / AFP

Habeck passes Greenpeace activists as he heads into a press conference on Monday of this week. Foto: JOHN MACDOUGALL / AFPWithin the Green Party, though, strict opponents of nuclear power began gathering their forces.

Many are concerned about a nuclear accident and have been working their entire political lives to phase out the technology – and are unwilling to compromise so close to the finish line.

Others are concerned that the party simply wouldn’t be able to absorb the rupture of this final taboo.

It would amount to the betrayal of so many battles over nuclear power in the party’s past.

On July 17, Habeck asked the grid operators to perform a second stress test, including all possible risks, some of which continued growing throughout the summer.

And to include an extreme scenario, analyzing what would happen if all risks were to become reality at the same time.

The experts were again asked to determine whether an extension of the lifespans of Germany’s remaining reactors beyond the phaseout date of Dec. 31 would be beneficial.

Habeck’s staff wanted to know if there was a risk of grid collapse.

And electricity prices were also rising, so they included a question regarding possible influences on electricity bills.

The stress test was yet another attempt by the economy minister to bypass the debate by transforming it into a technical question rather than a political one.

The political question was: What do we want to do?

The technical one: What does the data say?

And it also was a way for Habeck to buy time.

Whenever the question arose as to what was going to happen with the nuclear reactors, he could simply respond that the experts were still looking into it.

But then, they delivered the data, and the grid operators came to the following conclusion: Under the two pessimistic scenarios, Germany’s power supply could be at risk.

And the three reactors operating at reduced capacity in the winter could alleviate the problem somewhat.

Their contribution, the experts said, wouldn’t be huge, but it would be more than nothing.

Still, it was enough to remove Habeck’s option of simply shutting down the power plants as planned.

And it also meant that he suddenly had a problem with his own party.

Country Over Party

Just how great the agitation is can be seen by rumors that began making the rounds, according to which the minister had defined the stress test criteria in such a way that an extension of reactor operations would appear mandatory.

Some Greens even voiced suspicions that Habeck is eyeing a run for the Chancellery in 2025 and hopes to campaign as a politician who prioritizes the interests of his country above the convictions of his party.

A huge number of Greens, of course, would put the country’s interests above those of their party in the vast majority of instances.

But when it comes to nuclear power, the decision isn’t nearly as clear-cut.

The result was that, until recently, there were two opposing positions within the party.

Habeck believed that extending nuclear operations was necessary, while other Greens – including parliamentary group leaders Britta Hasselmann and Katharina Dröge, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and leftist heavyweight Jürgen Trittin, along with many party members in the state of Lower Saxony who were on the front lines of numerous battles over nuclear power in the past few decades – wanted the nuclear phaseout to be completed as planned at the end of the year.

Even as the stress test was still underway, toward the end of August, the idea was developed of shutting down the reactors as planned, but keeping them on standby should they be needed, as a kind of compromise.

Technically, that would mean that the reactors would be taken off the grid, but would remain at the ready if needed.

Should an analysis in December or at a later date come to the conclusion that Germany’s power grid was facing overload, the reactors could be restarted. Economy Ministry staff have insisted that the idea was developed in-house.

Habeck’s people then checked with the operators how long they would need to restart a reactor that had been shut down.

At a meeting of Green Party parliamentarians last week, the issue was the focus of intense discussion, and talks continued into the weekend.

There are competing narratives as to when, exactly, the decision to keep the reactors on standby was made.

Either way, Green Party parliamentary group leaders were informed on Monday morning of the current status of the debate.

But the details were apparently not quite nailed down by then.

That afternoon, Habeck appeared before Green Party lawmakers.

Members of the parliamentary group would later proudly claim that the floor leaders, together with Baerbock, forced Habeck to abandon the idea of keeping the reactors running.

That is the first of two narratives – namely that there was a power struggle inside the party and Habeck lost.

But the second narrative holds that Habeck did, in fact, have to back down from the idea of keeping the three reactors running, but that he tried to outflank the Greens with his alternative idea of keeping them on standby should they be needed.

In winter, after all, it isn’t unlikely that the worst-case scenario will become reality and continued reactor operations will become inevitable.

The "Standby Trick"

That would essentially translate to a de facto extension of reactor lifespans, but only after state elections in Lower Saxony, scheduled for four weeks from now, and after the Green Party congress.

"There is a lot to be said for this theory," says an energy expert who works with the Economy Ministry.

"Essentially, Habeck bought himself some time with the standby trick."

If that actually was the plan, it was blown up by someone who actually would have benefited from it.

In a letter to Patrick Graichen, state secretary in the Economy Ministry, Guido Knott, CEO of PreussenElektra, which operates one of the three nuclear reactors in question (Isar 2), communicated a rather devastating message.

The ministry’s proposal "to send two of the three operational facilities into standby at the end of the year, to then switch them back on as needed, is not technically feasible."

The letter was published on Wednesday.

Knott warned: "The testing of a start-up procedure that has never been tried before should not be done concurrently with a critical electricity supply situation."

In other words, those who consider nuclear power to be a dangerous technology can certainly not support the standby model.

Whether it’s true, however, remains unclear.

There aren’t many bodies capable of independently evaluating Knott’s claims.

EnBW, the company which operates another of the trio of reactors (Neckarwestheim 2), announced that it was in contact with the ministry, and only after that would it be possible "to assess the technical and organizational feasibility of the proposal currently under discussion."

The operators seemed confused that, following their initial discussions with the ministry, the standby idea was proposed as a potential solution.

The kerfuffle comes at an awkward time for Habeck.

Rises and falls in the political world tend to follow a preordained script: Those who rise too high are bound to fall.

And Habeck was on the rise for a long time.

His way of discussing uncertainty and decision-making has earned him no small amount of praise.

In a survey asking German voters who they would rather have as chancellor, Habeck recently came out ahead of Olaf Scholz.

A Serious Situation

But impressions have changed over the last few weeks.

First, the plan to allow natural gas companies, including highly profitable ones, to pass on higher prices to consumers in the form of a levy has triggered intense criticism.

A television appearance this week resulted in further derision.

Even after multiple follow-up questions as to whether he believes this winter will see a wave of insolvencies, Habeck’s position remained inscrutable for many.

Very few are of a mind to give the economy minister the benefit of the doubt at the moment.

In many people’s eyes, he flew too high for too long.

And the situation is too serious.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario