America’s Office Glut Started Decades Before Pandemic

Federal tax breaks dating to the Reagan years, and low interest rates, spurred developers to build too many office towers

By Konrad Putzier

Office vacancy rates are highest in older buildings, such as 100 East Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee. / PHOTO: MIKE DE SISTI/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL/REUTERS

A surplus of empty office space threatens to hollow out U.S. business districts.

Don’t blame the pandemic.

America’s office glut has been decades in the making, real-estate investors, brokers and analysts say.

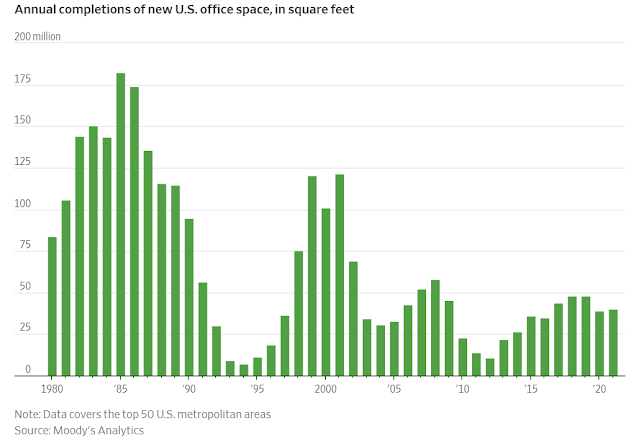

U.S. developers built too many office towers, lured by federal tax breaks, low interest rates and inflated demand from unprofitable startups.

At the same time, landlords largely failed to tear down or convert old, mostly vacant buildings to other uses.

As a result, the country has too many offices and too few companies willing to pay for space in them.

The rise of remote work during the pandemic aggravated a problem that was already emerging, analysts say.

The office surplus is primarily an American issue.

About 19% of U.S. office space was vacant in the second quarter, compared with 14% in the Asia-Pacific region and 7% in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, according to brokerage JLL.

Analysts expect that share to grow as more leases expire and more companies cut down on their real estate.

High office vacancies threaten the finances of building owners and their lenders.

They also harm the economies of cities such as New York and San Francisco, which rely on cubicle farms to pay taxes and sustain nearby shops and restaurants.

The U.S. office glut traces its roots to a 1981 change in the tax code, brokers and analysts say.

In a bid to boost the economy, the Reagan administration allowed investors to depreciate commercial real estate much more quickly than before, among other changes, lowering their tax bills.

Savings-and-loan associations showered developers with easy loans, brokers say.

That helped ignite an office-development boom in the 1980s that drove up vacancies to record levels and contributed to the savings-and-loan crisis, when many such institutions failed.

Vacancy rates slowly fell in the 1990s, but surged again after the bursting of the dot-com bubble and the subprime mortgage crisis.

In the decade after the 2008 subprime meltdown, office demand started to wane.

More companies reduced their office space to cut costs.

Firms realized they could save money by ditching private offices and cramming more employees into open floors.

Some started allowing remote work.

And yet the supply of office space kept growing.

Substantial tax breaks and other subsidies over the past two decades went into projects such as New York’s Hudson Yards and the World Trade Center.

Conversions of old, empty office buildings into warehouses or apartments remained rare.

Landlords became more adept at inflating rents in return for giving tenants cash gifts and other incentives, creating a mirage of a strong market.

Low interest rates and a flood of global capital into the U.S. real-estate market propped up the values of buildings even as demand for offices fell, giving their owners a false sense of security.

These factors masked chronically high vacancies and prevented landlords from pursuing more conversions, said David Lipson, president of real-estate brokerage Savills North America.

Sam Zell, chairman of Equity Group Investments, said co-working companies such as WeWork Inc. also contributed to an oversupply of office space.

Looking to grow quickly, such companies leased far more space than they could fill with customers in the years before the pandemic, covering their losses with billions of dollars from venture investors.

“By obfuscating those numbers we encouraged developers to come in and add office space in markets where there was no demand,” Mr. Zell said during New York University’s annual REIT Symposium earlier this year.

Chicago’s LaSalle Street, crowded with office towers, is now “a nowhere land with a whole bunch of obsolete buildings,” he added.

Vacancy rates are highest in older buildings, which lack modern amenities and are less environmentally efficient.

In Milwaukee, 100 East Wisconsin Avenue was the second-tallest building in the state when it opened in 1989.

Two blocks from a freeway exit ramp and with a 750-car garage, the 35-story tower was perfect for office workers commuting from far-flung suburbs.

But in the years before the pandemic, developers built a number of glassy new office towers nearby that lured away 100 East Wisconsin’s biggest tenants.

Today more than half the building sits empty and the two biggest remaining leases are set to expire next year, according to data from CoStar Group and a person familiar with the matter.

Unable to pay the mortgage, owner Hertz Investment Group handed over the property to a receiver in early 2021.

A number of investors have offered to buy 100 East Wisconsin to turn it into apartments, said Jared Friedman, senior managing director at the building’s manager, Friedman Real Estate.

The building has relatively small floors, making it a good candidate for a conversion, he said.

But many other aging office buildings lack such attributes, brokers say.

High interest rates and rising construction costs also make conversions more difficult.

“It’s not going to be the savior of all that obsolete office space,” said Julie Whelan, global head of occupier research at brokerage CBRE.

Instead, many old office buildings likely will end up under the wrecking ball.

Brokers say the process will be slow because property owners often don’t want to accept that their investment is lost.

A drop in new office construction could help the market recover, but will also take years to have an impact.

In the meantime, vacancy rates are expected to keep rising.

Some analysts estimate that remote work could reduce demand for office space as much as 20% for many years to come, although some brokerage firms project a smaller drop.

More buildings will likely end up in foreclosure.

“Time solves all problems,” said Mr. Zell.

“The pain between here and there can be very significant.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario