"Anything Seemed Better than Lying Dead in Mariupol"

Ukrainians Speak about Being Taken to Russia

Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians are being brought to Russia against their will. Here, two of them describe how Moscow lures them with welcome money and jobs, dividing them into two camps.

By Katrin Kuntz und Dmitrij Leltschuk (Photos) in Brussels and Talinn

Actor Vladyslav Krasnikov in his cabin on the cruiseferry Isabelle in Tallinn, Estonia: Around 1,800 Ukrainian refugees are being accommodated here. Many fled from Russia. Foto: Dimitrij Leltschuk / DER SPIEGEL

Vladyslav Krasnikov was a theater actor in Mariupol.

Sometimes, he played Puss in Boots, sometimes a judge or a man of the people.

He loves the stage, and he knows how to study his surroundings and transform himself into a character.

But to take a role in his own life and become a Russian citizen – it's not one that he wanted.

Not for money, not for gifts, not for the jobs offered to him by the Russian state.

Nor was he enticed by the prospect of a warm bed in the village in central Russia to which the Russian authorities had taken him and hundreds of other Ukrainians.

Krasnikov didn't want to budge.

"I just wanted to get out of Russia," he says.

He arrived on a July day on the 11th floor of the Isabelle, a cruiseferry in the port of Tallinn, the capital of Estonia.

This is where he is now living. Before the coronavirus pandemic, the ship transported tourists between Riga and Stockholm; now it accommodates around 1,800 Ukrainians who have fled.

Krasnikov, 23, is a diminutive, wiry man with blue eyes and good posture.

When he walks across the deck of the ship, it looks like he's moving on a stage.

Before the Russian attack he lived with his cat in the Ukrainian port city of Mariupol.

When he wasn't acting, he wrote poetry and read nonfiction.

When he tried to flee from the attacks on his city in the spring, he ran into Russian soldiers.

Then, as has presumably happened to hundreds of thousands of his fellow citizens, he was deported to Russia.

Ukranian Vladyslav Krasnikov in Tallinn: After he fled from Mariupol the Russian authorities brought him to a village in Central Russia, where he was asked to switch citizenship.

Ukranian Vladyslav Krasnikov in Tallinn: After he fled from Mariupol the Russian authorities brought him to a village in Central Russia, where he was asked to switch citizenship. Foto: Dimitrij Leltschuk / DER SPIEGEL

According to a ruling from Moscow published on March 12, Ukrainians can be distributed to places ranging from the North Caucasus to the country's far east.

Ukrainians seeking help registered in Perm near the Ural Mountains and even as far away as the Pacific island of Sakhalin in the east.

"The Russians acted as if they were helping us," Krasnikov recounts, with astonishment in his voice.

He shares a cabin on the ship in Tallinn with two men, one of them an old school friend from Mariupol. He eats in the dining hall three times a day.

Sometimes, he goes for a walk on the Isabelle, through the empty casino, past the duty-free store, where expensive cosmetics were once sold and the bags of refugees are piled up today.

When he wants to leave the ship, he takes the elevator down and checks out with a boarding pass.

But it's a manageable life compared to the odyssey that lies behind him.

Ukrainian refugees on the Isabelle: According to estimates published by the United States government, between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainian citizens have been deported to Russia since the beginning of the war.

A number of them traveled from there to Estonia and found shelter on a cruise ship.

Ukrainian refugees on the Isabelle: According to estimates published by the United States government, between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainian citizens have been deported to Russia since the beginning of the war. A number of them traveled from there to Estonia and found shelter on a cruise ship. Foto: Dimitrij Leltschuk / DER SPIEGEL

Ukrainian refugees on the Isabelle: According to estimates published by the United States government, between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainian citizens have been deported to Russia since the beginning of the war. A number of them traveled from there to Estonia and found shelter on a cruise ship. Foto: Dimitrij Leltschuk / DER SPIEGELAccording to estimates published by the United States government, between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainian citizens have been deported to Russia since the beginning of the war.

Many come from the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics located on the Russian border, but also from newly occupied places in the Donbas, reportedly even from areas near Kharkiv and Kyiv.

Since Feb. 24, some 50,000 Ukrainians have fled to Estonia, mostly through the border crossing near the city of Narva.

Some, like Krasnikov, have come from deep inside Russia.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy called the abduction of Ukrainian citizens one of the "most heinous Russian war crimes."

And it is a violation of the Geneva Convention for the protection of civilians in war.

Moscow, though, has made no secret of the practice and confirmed in July that 1.5 million Ukrainians were in Russia.

Russian propaganda refers to the deportations as "evacuations."

"We will definitely help the Ukrainian people to free themselves from the regime that is absolutely anti-people and anti-history," Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said in July.

The two peoples would live together in the future, he said.

Krasnikov, though, has experienced what that means firsthand.

The actor lasted barely a month in the spring in embattled Mariupol, witnessing at close range the bombing of his theater.

He hid in a backyard used by Russians to fire artillery.

He witnessed death, harassment, destruction and looting, and eventually the horror became too much for him.

He left the bombed city on March 27.

The destroyed theater in Mariupol: Krasnikov was at the site when it was bombed on March 16. Foto: Peter Kovalev / ITAR-TASS / IMAGO

The destroyed theater in Mariupol: Krasnikov was at the site when it was bombed on March 16. Foto: Peter Kovalev / ITAR-TASS / IMAGOTogether with his godfather, his child and a friend, Krasnikov found his way to the collection point for those willing to leave the country at the central hospital in Mariupol.

They boarded a bus belonging to the Russians, which took them to a registration center in Nikolske near Mariupol.

There, Russian soldiers asked the fleeing Ukrainians whether they wanted to go to Russia or elsewhere in Ukraine.

"In Ukraine," the responded, according to his account.

A short time later, they were told that Ukrainian troops were shelling the escape corridor.

"We're going to Russia," the soldiers told them.

Krasnikov says they were given a choice between Taganrog and Rostov-on-Don, both not far from the border.

According to Krasnikov, the fleeing Ukrainians opted for Rostov, the larger city.

"And this is where this story of grand Russian deceit begins," Krasnikov says.

Thousands of Ukrainians Are Disappearing into Camps

The bus took them to a camp on the Russian border, where the arrivals were interviewed and then divided into combatants and civilians.

At least 20 of these "filtration camps" reportedly exist in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine, the Ukrainian representative to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) estimates.

As soon as Ukrainians pass a Russian checkpoint, they are registered and questioned by the officials there.

They are also examined for suspicious tattoos, battle scars and bulges that might indicate they are carrying a weapon.

They also check their mobile phones.

Some Ukrainians remain in these filtration camps for weeks or are transported from there to prisons.

Evidence is mounting that Russian authorities are "detaining or disappearing thousands of Ukrainian civilians" who stand out during the selection process, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in mid-July.

Ukrainians who fell into Russian captivity and were later released have reported physical and psychological torture.

Ukrainian actor Krasnikov shows a picture of himself on the train that took him to Kinel-Cherkassy in Russia.

Many refugees were extremely exhausted from the exertion of fleeing and were happy to be safe in Russia.

Others, including Krasnikov, couldn't get used to the idea of living in the aggressor country.

Ukrainian actor Krasnikov shows a picture of himself on the train that took him to Kinel-Cherkassy in Russia.

Krasnikov says that he repeatedly told the Russians during interrogation that he didn't fight because he was the only son of his elderly parents.

He didn't have a mobile phone with him because it had been lost in the destroyed theater.

After 10 hours, the group continued their journey.

Krasnikov says the people in the bus were too exhausted to care where they were being taken.

Instead of going to Rostov in Russia, the minibus went to the port city of Taganrog, a hub for the distribution of Ukrainians in the country who have fled the war.

They are gathered in gymnasiums here before being sent further.

"At the train station in Taganrog, we were told to get on a train to Tolyatti," which is located 1,300 kilometers further northeast of the Volga River.

The collection point for fleeing Ukrainians had been moved there.

"Can we say no?" he asked the Russians.

He says they answered: "You can go wherever you want."

They were told that nobody would be forced to continue their journey.

But what alternative did they have?

"You're standing at a train station in a foreign country with no money, you haven't washed in a month and a half.

There are armed soldiers all around you," Krasnikov says almost apologetically.

He boarded the train.

When Krasnikov's group arrived in Tolyatti in early April after a 10-hour trip, soldiers and journalists were waiting for them.

Krasnikov and the fellow travelers were paraded as the Ukrainians who the Russians had saved from the Nazi government in Kyiv.

The journey then continued to a children's sanatorium in the nearby village of Kinel-Cherkassy.

Here, 1,000 kilometers away from Moscow, near the border with Kazakhstan, Krasnikov was to regain his strength after the horror of war and flight.

"I'd love to say something bad," Krasnikov recounts, "but they took good care of me."

There was food, and he had a bed in a four-person room.

But he also had a bad feeling, because now others were writing his story – as that of a saved man.

The government-aligned Social Newspaper, which is produced in the large city of Samara not far away and has 50,000 subscribers, ran a report about the newcomers in the sanatorium at the end of April.

The intro to the article states: "'We escaped from hell,' say Donetsk refugees who found refuge in Samara.

Now they are learning to live again – without fear, without explosions and a hail of shells."

The article portrays Russia as being the Ukrainians' savior.

Jobs in Exchange for Passports

Each day, the authorities approached the 200 newcomers with offers, bank employees had them sign up to open accounts so they could get the state welcome money of 10,000 rubles, the equivalent of 160 euros.

Employees of social welfare agencies took care of families, and a car plant and a sewing factory offered jobs.

Officials also offered the Ukrainians Russian citizenship.

Krasnikov refused the Russian passport, but he did open a Russian bank account.

He was given shaving cream and underwear.

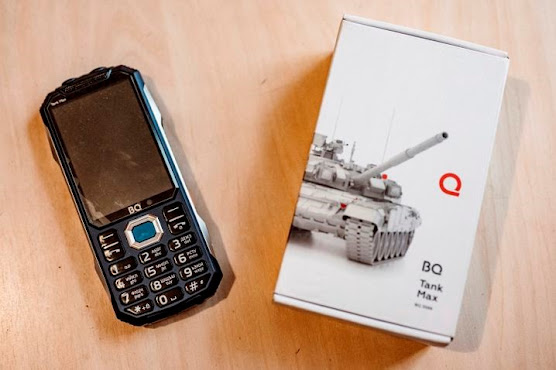

The regional administration bought him an old-fashioned mobile phone. Krasnikov still has it with him.

"For cracking nuts," he says, mockingly holding up the ancient model.

The Russian authorities gave Vladyslav Krasnikov a mobile phone after his abduction.

His old one had been destroyed in the bombing of the theater in Mariopol.

The new one came in a package with an image of a Russian tank on it.

The Russian authorities gave Vladyslav Krasnikov a mobile phone after his abduction. His old one had been destroyed in the bombing of the theater in Mariopol. The new one came in a package with an image of a Russian tank on it. Foto: Dimitrij Leltschuk / DER SPIEGEL

The Russian authorities gave Vladyslav Krasnikov a mobile phone after his abduction. His old one had been destroyed in the bombing of the theater in Mariopol. The new one came in a package with an image of a Russian tank on it. Foto: Dimitrij Leltschuk / DER SPIEGELIn the evening, musicals were performed in the Cosmos Room of the Children's Sanatorium, which was reminiscent of a space station.

The helpers even organized nightclub dance evenings for the Ukrainians.

"They wanted to make things easier for us," Krasnikov says, bitterly.

He says many accepted it and that there had been no effort to resist or criticism.

"We had no energy.

Everyone was just happy to be safe."

After a few days, a division became visible among the deportees – into "those who were grateful to Russia for the help and those who hated Russia."

For him, staying had never been an option.

"Not in a country that is destroying our lives."

When Krasnikov began feeling better after three weeks, he requested a train ticket to St. Petersburg from the local helpers.

His godfather, his child and the friend joined.

No one stopped them. Their request to continue her journey was approved without any problems, he says, and although the helpers did try to persuade them to stay, they ultimately paid for the ticket.

After 35 hours on the train and an ensuing bus ride, Krasnikov and his fellow passengers arrived in the Estonian border town of Narva.

In Narva, about three hours by train from Tallinn, between 10 and 30 Ukrainians currently arrive each day, volunteers helping the refugees estimate.

Those who want to stay in Estonia are provided with support.

Those who want to continue their journey can take a bus to Riga or Prague.

In the nearby offices of the aid organizations, you meet people who were still in Mariupol only a week ago.

You can see the terror and exhaustion in their faces.

Nevertheless, many still find warm words for Russia, with some emphasizing Moscow's help in rebuilding the city.

People at the Russian-Estonian border in Narva: Some of the people here were still in Mariupol only a week ago.

You can see the terror and exhaustion in their faces.

It's not easy to find people who shared Krasnikov's experience among the 1,800 inhabitants of the refugee ship in Tallinn.

Most of the Ukrainians you meet in Estonia entered via Russia; however, many have lived with relatives there and didn't have any experiences involving deportation.

Around 1,770 kilometers as the crow flies from Narva, Valeriya Korbonova is sitting in a Brussels café on a recent summer day.

The 22-year-old has her dark hair tied back in a ponytail and is wearing a black and white plaid shirt, black jeans and sneakers.

She doesn't stand out in the crowded city. Like Krasnikov, she was born in Mariupol and worked there as a cosmetics salesperson.

Earning money, decorating her apartment nicely, going out with friends – that was her life.

Korbonova survived a missile strike in Mariupol.

When shrapnel from a bomb pierced one of her boots, she said, her friend yelled at her not to cry, there was a man lying next to her with no head.

She goes to smoke every 30 minutes.

She also left Mariupol in a bus of Russians who told her that it was too dangerous in Ukraine.

She passed through a filtration camp in Novoazovsk, which has been part of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic since 2014, where she had to strip down to her underwear.

Like Krasnikov, she was taken to Taganrog.

In the gymnasium there, she says helpers told her she would be going to Khabarovsk, deep in eastern Russia.

"You can find your dream job there."

She says she wasn't given any choice in the matter.

But, Korbonova says: "Anything seemed better than lying dead in Mariupol."

Together with her sister and her sister's family, she boarded the train that traveled across Russia.

The journey lasted nine days.

She says the views were wonderful.

Meadows, deep forests.

The train stopped every now and then and they would buy vodka.

She recounts that the 550 refugees from Mariupol arrived in Khabarovsk on April 29 at noon.

Here, too, there was a crowd at the station.

"Everyone wanted to talk to us."

Korbonova says she pulled her hood over her head until she arrived at her new accommodations.

On the video that she later showed to the New York Times, you can see a neatly prepared room with a television.

Unlike Vladyslav Krasnikov, Korbonova tried to start a new life in Russia.

The choices presented to her by the employment office included becoming a "cleaning lady, an administrator or ticket controller" on public transportation.

They wanted to pay her around 15,000 rubles a month, the equivalent of about 250 euros.

In order to work, though, she would have had to give up her Ukrainian passport and take Russian citizenship.

There was also a condition that she not leave the Khabarovsk region for the time being.

For that they offered her another 650,000 rubles, about 10,600 euros.

"I didn't want to do that," she says.

On the internet, Korbonova came across an aid network for abducted Ukrainians.

Using the messenger app Telegram, she got in touch with a woman in Russia who had connections to Estonia.

The helper got her a plane ticket to Moscow, and from there Korbonova traveled by train through St. Petersburg to Narva and then on to Brussels on May 22.

She is now learning English with a host family.

She wants to earn money, maybe as a warehouse worker and then quickly return to Ukraine.

Krasnikov, the actor from Mariupol, also has plans.

On the ship, he talks about his new job at the city's Russian-language theater.

He found employment here after applying at only three places.

But he doesn't feel like he has arrived.

He mourns the people who died under the rubble of the theater in Mariupol.

He wants to seek advice from a psychologist because he feels guilty about having survived.

While parts of the former ensemble continue in western Ukraine, others are rebuilding the theater in Mariupol with the Russians.

In September, the theater is scheduled to stage its first play since the attack.

In Russian.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario