Prosperity Under Pressure

Germany and the End of Globalization

The number of democratic countries around the world is shrinking steadily, and autocratic countries are registering more patents than the West. A new era is dawning – and it could have dramatic consequences for our work, our money and our lives.

By Thomas Schulz, Martin Knobbe, Martin Hesse, Simon Book, Simon Hage, Georg Fahrion, Michael Sauga und Gerald Traufetter

Foto: Mario Tama / Getty Images

These days, even stoic government leaders seem overwhelmed by the barrage of world crises, tremendous upheavals and changing times.

The global financial crisis, the refugee crisis, Brexit, the climate collapse, the coronavirus pandemic and the war in Ukraine have all happened in succession.

It's more than enough to make a person dizzy.

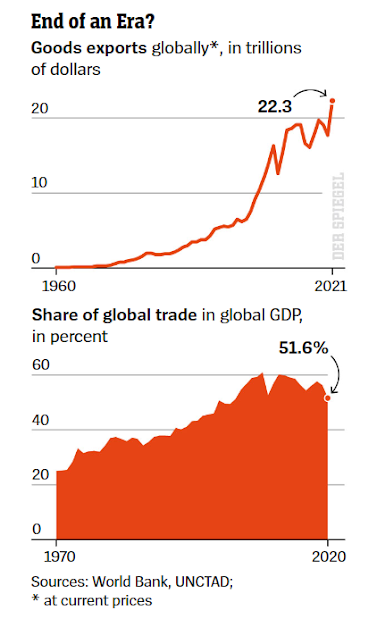

And yet, all this now simply feels like a preview for the massive change that is only now starting to role in: The age of globalization is coming to an end.

Six months ago, that very sentence would have seemed laughable.

Economists had calculated that even the pandemic was just a dent in the never-ending frenzy of global trade.

Politicians had declared that the ever-growing interdependence of nation-states remained one of the few irrefutable certainties of world politics.

The best way forward to a good future, they would have said, would be to move even closer together, networking trade, companies and the economy even more deeply.

Globalization has never been a purely economic phenomenon.

For three decades, it was the defining world order, the guiding principle informing all political decisions.

It determined how and where we work and how well we live and even who is a friend and who is a foe.

Linked to this was a clear vision of the further development of humanity: that the world would become ever more prosperous, and thus necessarily ever more modern, ever more liberal, ever more democratic.

And that it would constantly become more Western.

That economic ties would also create common values.

And, more importantly: peace – at least more than ever before.

But all of these supposed certainties have just been steamrolled by Putin's tanks.

These days, everybody who is anybody is proclaiming the death of globalization.

The "system of international cooperation" that has "guaranteed us freedom, security and prosperity" over the past decades is at stake, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz said at the World Economic Forum in Davos at the end of May.

"Instead of relying on foreign supply chains, let’s make it in America," United States President Joe Biden urged during his State of the Union Address this spring.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has proposed conducting trade primarily with friendly countries.

"Globalization as we knew it will not return," BASF CEO Martin Brudermüller recently said in an interview with DER SPIEGEL.

"We are now living in a whole new era," Henry Kissinger has said.

Most business leaders share this view.

They are looking for new supply chains, reducing their dependence on individual countries and relocating production capacities.

Foreign capital is fleeing China, and with it a large number of international workers.

These are all clear signs that globalization has not only stalled, but that trade has gone "in reverse,” says Jerome Powell, head of the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Safety first.

"Freedom is more important than free trade," is how NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg frames it.

Nations around the world are once again striving for economic independence.

And the war in Ukraine wasn’t the first nail in the coffin.

Attacks on globalization have been mounting for years: Donald Trump launched a trade war with China, the United Kingdom left the European Union, populists from Hungary to Brazil have sought to re-nationalize their economies.

Between 2008 and 2019, global trade shrank by almost 5 percent, while global investment halved between 2016 and 2019.

Initial calculations by the World Bank suggest that the Ukraine war will cause global trade to shrink by at least another 1 percent.

For now, anyway.

Global trade won’t collapse entirely, of course.

Economies and companies are too closely networked, and the mutual dependencies are too great.

Still, as German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock puts it, "it has already been proven wrong that trade alone creates change."

And the thesis of the "end of history" promoted by the political scientist Francis Fukuyama shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall and often used in the past as justification for unrestricted hyper globalization, has proven to be just as wrong: The thinking was that liberal democracies and Western market economies would inevitably prevail as the dominant political order.

But for the past several years, studies have noted that freedom and democracy are in retreat worldwide, and that autocratic regimes are on the rise and are becoming more powerful.

Between 1970 and 2010, the share of democratic governments in the world more than doubled to 53 percent.

Since then, however, the trend has been steadily downward.

At the same time, autocracies are increasingly successful economically.

They are now the source of a 60 percent share of all patent registrations.

So, if world trade actually strengthens autocracies rather than weakens them, then this raises complicated questions, particularly for Germany, a country whose economy is particularly reliant on exports.

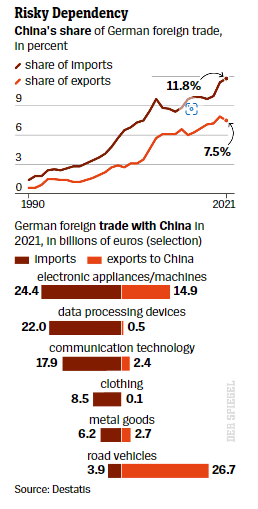

Can China remain such a close partner?

Or Turkey?

Autocracies are now the source of 60 percent of all new patent registrations.

In Europe, there are already discussions about retreating more into national borders to become more independent, more self-sufficient, to decouple from the world.

It is a trend that has so far been reserved for populists like Donald Trump, because it symbolizes supposed national strength, but tends to be frowned upon by economists because there is little more to it than economy-constricting protectionism.

The consequences, that much is clear, will be severe, particularly for Germany.

The country's economic dependence on China is almost as considerable as its reliance on Russian gas.

At the same time, there are also opportunities, at least in the long term.

In Berlin and Brussels, a lot of thought is currently being given to what a different, better globalization might look like.

This new era, many expect, could be that of a strong state.

Berlin: Searching for a New Model

Traveling with German Economy Minister Robert Habeck on his numerous trips in recent weeks – to places like Jordan, Israel, the United States and Qatar – reveals a man on a mission.

Many of the things on his to-do list are concrete: Gas, oil.

New trading partners.

But others are more elusive: finding a new model of prosperity for a country that benefited more than any other from hyper-globalization as is now watching nervously as the world order disintegrates around it.

Germany has lived well in the past decades.

Since 1990, the country has almost quadrupled its foreign trade in goods and services.

During the same period, adjusted per-capita income increased by almost 50 percent.

If globalization shrinks, Germany shrinks.

"Our prosperity is at stake," says Clemens Fuest, president of the prestigious Ifo Institute, a leading economic think tank.

That may sound alarmist, but there are plenty of indicators.

The revenues of many German companies in China are falling.

Fewer German machines are being purchased around the world.

And everything is getting more expensive.

The more the world de-globalizes, the more vulnerable becomes the German model of success, which relies on open markets.

It’s late in the evening, and Habeck, who is also the vice chancellor, is sitting by the pool of a secured hotel in Amman, thinking about how to proceed.

There must be a way forward, he says, a new form of globalization, created with Germany’s help, a "fairer and more sustainable one."

With a "new European trade agenda" in which security and moral considerations play a significant role.

Habeck believes that China, under President Xi Jinping, has exploited its economic power in the pursuit of its geostrategic goals.

In the future, he argues, Germany and Europe will have to counter that with economic policy rules based on their own Western values.

At the end of May, the German government canceled investment guarantees for Volkswagen in China because the global corporation has a factory in the Uyghur region of Xinjiang, where Beijing conducts widespread oppression.

In exchange, Habeck wants to find the unifying aspects among those who embody democratic values, as he explains on another occasion.

An axis consisting of allied international leaders like Joe Biden of the U.S., Emmanuel Macron of France, Mario Draghi of Italy and Justin Trudeau of Canada.

The window of opportunity for such a project could be small: Indeed, Donald Trump could soon be back on the world stage.

Were that to happen the U.S. would only be half an ally. At most.

The groundwork, Habeck says, needs to be laid immediately.

In the form of things like free-trade deals modeled after the CETA agreement between the EU and Canada.

It still hasn’t been ratified by all the member states, including Germany.

Such ideas are not without danger for the vice chancellor, who is a member of the Green Party.

In recent years, his party has been fond of brainstorming about what a defanged capitalism might look like.

How prosperity could be maintained with significantly fewer resources.

A capitalism based on an "ecological economy," one that would perhaps have no growth at all.

Such ideas have long been considered more of a political ideology, firmly rooted in the Green Party.

And the would trigger heated discussions within the federal government in Berlin, a coalition between the center-left Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party and the business-friendly Free Democratic Party (FDP). In terms of economic policy, the SPD, the Greens and the FDP are far apart.

It’s indeed striking that the SPD is far less clearly positioned on the discussion of sustainable capitalism than the Greens.

So far, in his administration, Chancellor Olaf Scholz has been navigating the issue largely on his own.

And he has to be careful not to be overtaken in the process by his eager vice chancellor.

Accordingly, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Scholz emphatically outlined his ideas for a new world order "in which very different centers of power can interact reliably in the interests of everyone."

The leaders of the BRICS emerging economies South Africa, India, China, Russia and Brazil: Increasing prosperity doesn't necessarily translate into increased democracy. Foto: Eraldo Peres / AP / picture alliance

The leaders of the BRICS emerging economies South Africa, India, China, Russia and Brazil: Increasing prosperity doesn't necessarily translate into increased democracy. Foto: Eraldo Peres / AP / picture allianceTo that end, the chancellor wants to "reduce some of our strategic dependencies."

At the same time, he is very careful not to use the term autarky, which has recently become fashionable.

Adam Smith, the father of liberal economics, espoused self-sufficiency as salvation from dangerous dependencies early on.

But the prosperity gains from free trade and the division of labor have long been too great for Germany to seriously be able detach itself from global value chains.

The result would be tariff wars and price explosions.

Economists at the University of Tübingen have calculated what would happen if Germany completely decoupled itself from world trade: The economy would shrink by nearly 20 percent.

How the chancellor envisions the coming world instead can be seen from the other guests he invited to the recent G-7 summit in addition to the six other leading industrialized nations and the European Union: India, Indonesia, South Africa, Senegal and Argentina.

Five countries from three continents - and Senegalese President Macky Sall is also the representative of the African Union, with its 55 member states.

Of particular interest are the invitations extended to India and South Africa, two of the so-called BRICS countries which, together with Brazil, Russia and China, form an association of emerging economies that has long considered themselves to be a clear antithesis of the powerful G-7.

Scholz and Habeck want to put an end to the primacy of the economy.

It's also a community that Chancellor Scholz has viewed with concern since the start of the Ukraine war.

The rift with the Western industrialized countries threatens to grow even deeper, and the BRICS states could gain more power in the world.

In his discussions, Scholz repeatedly warns against a false self-assessment of the West and against assumptions that all other countries see Western democracies see the Western model as the goal.

The chancellor has warned that such attitudes could drive African countries, in particular, into the arms of China and Russia.

But Scholz and Habeck, along with Green and Social Democratic thought leaders, do agree on one thing: The world should no longer be left to the mercy of the markets to the degree it has been.

The primacy of the economy must end.

New York: Financial Giant Blackrock Threatens China and Demands Greater Speed from Europe

If you were to hold a casting for the personification of globalization's winner, you would inevitably end up with Larry Fink, high up in a glass skyscraper in midtown Manhattan.

This is the home of Blackrock, a giant even among the world's financial giants, the master of over $10 trillion, a number that is almost three times Germany's gross domestic product.

Blackrock CEO Larry Fink: "Now companies are learning that secure production is even more important than producing cheaply." Foto: Damon Winter / The New York Times / Redux / lai

Blackrock CEO Larry Fink: "Now companies are learning that secure production is even more important than producing cheaply." Foto: Damon Winter / The New York Times / Redux / laiFink founded Blackrock in 1988, just as the new era of globalization was taking shape and the New York financial industry was preparing to help it get started.

The simple recipe: Suck up as much money as you can, invest it broadly and cheaply without actively searching for the best companies, and let the ocean of ever-growing financial capital carry you to the top.

Fink recognized that globalization and capital markets would form a symbiotic relationship: Financial investors tore down barriers and allowed unprecedented amounts of money to flow around the world.

More and more countries opened up to international capital, right up to China.

Stocks, bonds and commodity futures were shifted around the globe in milliseconds.

Swelling capital markets and a growing global economy kept feeding New York's financial specialists with trillions and trillions.

No other industry has become so rich and so powerful through globalization.

Blackrock holds stakes in 33 of the 40 companies on Germany's blue-chip DAX index as well as hundreds of other corporations around the world.

Fink, who is worth a billion dollars himself, advises leaders of countries and central bank presidents.

His annual open letters to the world's most powerful corporate leaders have become a kind of gospel of capitalism.

If you want to find out where things are heading, it's good to talk to Fink.

In the long term, he still believes in the internationally networked economy and the power of the capital markets, Fink says, sitting in front of a large world map, his brow furrowed. "

But the Russian invasion has ended the globalization we've had for 30 years."

Definitely.

So, what happens now?

"Companies will have to move more of their production and larger parts of their supply chains closer to their markets."

For decades, he says, everything has been geared toward producing more efficiently.

"Now, companies are learning that secure production is even more important than producing cheaply."

As are governments for whom economic independence is more important than maximum growth.

Fink is certain that international corporations will withdraw from some countries.

Not only because of the economic risks, but also because of moral risks.

"Companies today have to face political and social issues on a very different level," he says.

Fink doesn't say exactly which countries he is referring to, but he does name a few that could potentially benefit from this shift.

Mexico and Brazil, for example. Countries where production is cheaper, but where human rights are still largely respected.

But relocating production, abandoning markets and building new supply chains is expensive.

It will drive prices even higher.

"Unfortunately, one consequence is the comeback of inflation," Fink says.

At least until companies succeed in creating alternatives.

"I think it will take two or three years for new capacity to cause inflationary pressures to subside."

Fink knows that the new current is no longer stoppable.

When climate change became a mainstream issue and politicians finally began adopting countermeasures, Fink exhorted corporate bosses to be sustainable in his New Year's letter – even threatening to pull his capital out.

Now, Fink is also responding to the new, geopolitical threat to the financial world manifested by Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

"Access to the global capital market isn't a right, it's a privilege," Fink says.

He says Russia has been stripped of that privilege and that several hundred Western companies left the country "not only because of the sanctions, but because their stakeholders – shareholders, employees and customers – demanded it."

In principle, at least, he says this could also happen in other countries, adding that such thoughts are voiced regularly in Beijing.

This is Fink's way of pointing out the power of global corporations and investors.

They have a lot to lose if global trade shrinks.

And countries that seek to opt out of the networked economy and want to return to a world of hostile blocks have even more to lose.

As such, Fink warns Europe against pushing ahead with the formation of its own bloc and somehow decoupling itself from China.

"The leading tech companies come from the U.S., China and South Korea," Fink points out.

His advice for steering through the upcoming decade of uncertainty: "Europe needs to invest more in technology.

And the Germans need to get faster, too."

Brussels: The Agenda-Setter of the New Era

On a sunny early summer day, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is standing on the beach of the small Danish port town of Esbjerg.

She is dressed in the maritime colors of white and blue.

Behind her, the towering hulks of wind turbines rise into the sky; in the distance, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte are stumbling across a dusty field of pebbles with construction cranes rising above.

Where lecterns now stand, thousands of wind turbines will be loaded onto special ships in the next few years and transported out to sea for final assembly.

Within a few years, von der Leyen promises, the North Sea will be transformed into a "green power plant" that will supply millions of European households with electricity.

"The more independent we become of fossil energy," she says, "the more independent we become of Putin."

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and European Commission President Ursula von er Leyen at the North Sea Summit at the port of Esbjerg, Denmark, on May 18 Foto: Bo Amstrup / Ritzau Scanpix / picture allianc

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and European Commission President Ursula von er Leyen at the North Sea Summit at the port of Esbjerg, Denmark, on May 18 Foto: Bo Amstrup / Ritzau Scanpix / picture alliancThis is what it sounds like when the European Commission president appears in her favorite role as a great transformer.

Von der Leyen wants to make Europe the world's first climate-neutral continent.

Most importantly, the former German defense minister has dedicated herself to shaping the EU into a self-confident geopolitical actor, the defining force of the post-globalization era.

"Europe," her slogan goes, "must relearn the language of power."

Von der Leyen sees the EU in a position to finally fulfill the hopes long placed on it to become the global pacesetter for the 21st century.

As it happens, the EU spent decades followed a different maxim.

The union of nations viewed itself as an economic association that sought to enforce the values of the liberal constitutional state with the soft power of trade agreements, standardization bodies and competition rules.

Whereas the great empires of the Cold War still thought in terms of spheres of influence and blocs, the EU saw itself as a community of "market-conforming democracies," as former German Chancellor Angela Merkel once notoriously put it.

As an economic empire geared toward hyper-globalization, in which free trade, deregulated markets and the primacy of profits were the guiding principles.

This worked splendidly as long as freedom and growth seemed to be two sides of the same coin.

At least since the turn of the millennium, however, Europeans have become aware that the seemingly limitless rule of the market can be accompanied by new dependencies: on the internet corporations from Silicon Valley, for example, or on a new generation of unscrupulous power politicians who flout international rules.

By men like ex-U.S. President Donald Trump, in other words, who declared European cars to be a security risk to the U.S.

Or Chinese leader Xi Jinping, whose industrial strategy is based on squeezing EU companies out of important markets.

Von der Leyen has now set "sovereignty" as the slogan for the future.

Europe, she said in her State of the Union address last year, must shape economic restructuring "according to our own rules and values."

Prior to her comments, EU officials had listed all the places where the bloc has become vulnerable because it no longer produces important goods or services itself.

For example, 90 percent of European data is held in the cloud services of U.S. corporations such as Amazon or Microsoft.

Europe's market share in the manufacture of semiconductors is only around 10 percent.

The fast money of globalization has made the continent dependent.

Dependency on China is viewed with particular suspicion in Brussels.

Not only because China's raw materials are needed for the expansion of the European wind and solar industry or for electric motors.

But also because the country is at least as important as a sales market.

VW sells close to one-third of its cars in the People's Republic.

The country has long been the most important growth market for European luxury manufacturers such as the French LVMH Group (Louis Vuitton and Tiffany).

A common lament among many EU politicians is that the fast money of globalization has made the continent dependent.

"Much of European industry is based on cheap energy from Russia, cheap labor from China and highly subsidized semiconductors from Taiwan," says Margrethe Vestager, the Danish member of the European Commission.

"We weren't naive, we were greedy," she says.

It is undisputed in the EU that the community of states will now have to depart from the usual model of globalization and reduce dependencies.

And yet it remains to be seen how this balancing act will be achieved – how Europe will somehow become more independent without closing itself off.

More trade agreements, but the right ones.

Detaching itself from China, but without causing too much immediate pain.

There are heated arguments in Brussels about the correct way forward.

One group, led by Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton of France, wants to bring technologies and the manufacture of semiconductors back to Europe, with subsidies and billions of euros in targeted protectionist measures if necessary.

By contrast, his more market-oriented counterpart Vestager wants to seek out as many providers and customers as possible in different parts of the world.

She'd like to see globalization expanded rather than weakened.

The battle cry: diversification, not autarky.

European Commission President von der Leyen is hoping that her appearance on the Danish coast will show that there can be a middle way.

The Commission president promises that the accelerated expansion of wind power through the North Sea initiative will create tens of thousands of jobs in Europe.

At the same time, she says, the EU will need so much renewable energy to meet its climate goals that it will have to import additional green hydrogen from the sunny regions of the globe, through close relationships with trading partners in Africa.

It is time, von der Leyen said, "to replace old chains with new bonds."

Spain and Wolfsburg: German Industry Struggles for Greater Self-Sufficiency

Roberto García Martínez senses big business in the middle of Pampa, Spain.

He searches the ground with a magnet on a mountain plateau between eucalyptus trees and reddish-brown boulders.

There' s a click, and he stops at an inconspicuous stone.

Martínez grins: Hit.

Nickel.

He has detected one of the world's only three magnetic metals.

It is a valuable find, both financially and geo-strategically.

Especially from a German perspective.

Nickel is indispensable material for electric car batteries.

Martínez's company Eurobattery Minerals has spent 5 million euros here so far: drilling a dozen holes up to 200 meters deep, mapping the drill cores, cutting, rasping and pulverizing stone, and sending it to the laboratory.

Martínez wants to mine up to 65 million tons, build a road in Pampas and move an entire village.

His target net yield: 162,500 tons.

Current value on the commodities exchange: $4.1 billion.

A gold rush.

And Pampas is only the beginning.

According to the raw materials expert, all of Europe is full of mineral resources that are needed for batteries like the ones used in electric cars, in domestic electricity storage systems or wind turbines.

In the past, mining in Europe hasn't paid off.

But Martinez believes that consumers and industry are now willing to pay a premium for domestic raw materials, for the certainty of having them.

Some 2,400 kilometers away, Herbert Diess is making similar observations in provincial Lower Saxony, Germany.

Even in times of largely smooth globalization, Volkswagen's CEO wasn't entirely comfortable with how dependent the German auto giant has become on raw materials from Africa and Asia.

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, a crisis team at the company has been working to ensure that the supply of critical components doesn't suddenly stop.

Although VW's electric cars no longer need oil from Russia or Saudi Arabia, they do require vast quantities of lithium and cobalt. Cobalt mainly comes from the Congo, and lithium from Australia, Chile and China.

Volkswagen Group CEO Hebert Diess (pictured here) fears that Europe is overestimating its capabilities. Foto: Jens Büttner / dpa / picture alliance

Volkswagen Group CEO Hebert Diess (pictured here) fears that Europe is overestimating its capabilities. Foto: Jens Büttner / dpa / picture allianceAs far as the refinement of metal is concerned, it's hard to skirt around China.

The People's Republic produces 58 percent of the world's lithium and nearly two-thirds of its cobalt.

What if the Chinese decided to stop supplying German corporations or triple prices?

That would quickly put an end to any desired electro-revolution in Germany.

And to the golden age of the German automobile industry.

A non-diversified risk.

Not only for VW, but for the entire German economy.

So, what could be more obvious than to mine the necessary raw materials at our own doorstep?

Finland and Sweden are home to nickel deposits, and lithium can be found in Spain, Austria and Germany.

The Czech Republic has manganese deposits.

More difficult, says Peter Buchholz, is cobalt.

He's the head of the German raw materials agency DERA, which is part of the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources that advises companies on raw materials security on behalf of the German government.

He says he senses a "growing interest among many companies in obtaining their supplies from Germany and Europe."

In an internal study, DERA lists all known European mining projects for raw materials found in batteries.

Many new ones have recently been added. Could it really be possible for Europe to become self-sufficient in raw materials?

Europe is unable to supply more than 25 percent of the lithium that is needed here.

"No," says Buchholz.

Even in the unlikely event that all known projects were to deliver at 100 percent, it still wouldn't be enough to cover Europe's needs, he says.

For example, Buchholz says that lithium is "hot" right now.

But Europe is unable to supply more than 25 percent of the overall need here.

He says it's impossible to cover demand without South America and Australia.

The situation is similar with other raw materials used in batteries.

Buchholz believes it to be "unlikely" that the company will one day be able to supply itself from its own supplies.

Especially because it isn't strictly necessary.

He says there are enough mineral resources worldwide for the ramp-up of electro-mobility and the restructuring of the energy supply. Securing access is more important, he argues, with direct stakes in mining projects, for example.

Buchholz argues that there is no need for panic.

"So far, German companies have fared quite well with globalization, despite the growing country risks."

But that is hardly reassuring in Wolfsburg, where Volkswagen in headquartered, because raw materials are by no means the only dependency risk facing the automotive industry.

Few other industries have undergone as much fundamental globalization in recent decades.

Turning that back seems almost impossible.

At the very least, though, Diess wants to try to strengthen Europe as a business center.

Following the Russian invasion, VW had to shut down production in Germany for weeks because the company had until then sourced most of its wiring harnesses, the car's central nervous system, from Ukraine.

What if Beijing now also attacked Taiwan and supplies of battery cells from China and microchips from Taiwan suddenly dried up?

VW would then have to virtually shut down.

Although Diess doesn't believe that such a scenario is realistic, the VW group is nonetheless bracing for further supply chain crises.

The Wolfsburg-based company is examining how and where supply chains and production processes can be relocated to other countries or provided with double backup options.

Particularly when it comes to the battery, the heart of the electric car, the Germans have been striving for greater independence for some time now.

Volkswagen is investing several billion euros in six European battery plants.

And even that is only enough to cover 20 percent of the demand.

The other 80 percent will still have to come from global suppliers.

Generally, former innovation leaders like VW have long been dependent on foreign high-tech giants.

Chips, software and artificial intelligence for autonomous driving are created in Taiwan, Tel Aviv, California or Shanghai, not in places like VW headquarters in Wolfsburg or Audi in Ingolstadt.

"If Europe loses data sovereignty in the car," warns CEO Diess, "we will make ourselves completely dependent on high-tech corporations from the U.S. or China."

But the struggle for greater technological autonomy isn't yet going as planned for the Germans.

VW, for example, wants to grow its software subsidiary Cariad to become Europe's second-largest software company after SAP, as a bulwark against the competition from the United States and the Far East.

It's a multibillion-euro project.

But the company's new operating system has suffered numerous delays.

The consequence is that important new vehicles from Audi and Porsche - vehicles intended as competition for Tesla - are years behind schedule.

The VW CEO also thinks that the fact that the companies are based in Germany is part of the problem – the country is simply too weak when it comes to future-oriented technologies like AI or semiconductors.

Diess fears that Europe is overestimating its abilities.

Shanghai: Breaking Away from the West

For a moment, it seemed as if the way back to the old, better world was possible again.

After long, dark weeks, the doors opened on Nanjing Road, Shanghai's five-kilometer-long shopping mall, at the end of May.

The Adidas store is reopening, the local media reported.

The sporting apparel manufacturer recently got a taste of what it feels like when Beijing loses its taste for you.

In the past quarter alone, sales slumped by one-third compared with the previous year.

China used to be Adidas' most important market, but now it ranks only third.

Hopes that this will change are pretty low at this point, despite the reopening of Nanjing Road.

Adidas and other global corporations have been suffering for months from a phenomenon the Chinese call "guochao."

National pride as the basis for consumption decisions.

The days in which Western brands were welcomed with open arms appear to have passed.

That's bad news for the German economy.

With a trade volume of 245 billion euros, China is indisputably Germany's largest business partner.

And yet there is growing mutual antipathy.

International workers are leaving the country in droves.

German companies are having trouble finding European executives who want to work in China.

Surveys conducted by chambers of commerce representing the European Union, the United States, Germany and France show that more than three-quarters of the companies polled now consider China to be a less attractive place to invest.

On the surface, the exodus appears to be a product of the country's radical "zero-COVID" strategy.

The prospects of ever-new lockdowns and not being allowed to leave home for weeks at a time has discouraged international workers.

At the same time, the pandemic is merely a catalyst that is accelerating processes that Western companies and their workforces have been feeling for quite some time.

Under President Xi Jinping, the country has begun sealing itself off from the world.

Urban dwellers in China may use the latest iPhone, eat Australian steak, watch James Bond movies and listen to Rihanna as a matter of course.

They also know what is going on around the world, although that information is always filtered through the state-controlled media cosmos.

Chinese President Xi Jinping: The days in which Western brands were welcomed with open arms appear to have passed. Foto: Li Tao / Xinhua / IMAGO

Chinese President Xi Jinping: The days in which Western brands were welcomed with open arms appear to have passed. Foto: Li Tao / Xinhua / IMAGOSince the beginning of the pandemic, cross-border travel has been as impossible for most Chinese as it is for foreigners wanting to visit China.

The world outside, where the coronavirus is rampant and ostensibly anti-China forces would deny the country respect for its historical achievements, appears to be increasingly hostile.

Such is the view from China.

It used to be different.

The reform and policy of opening from 1978 onward brought increasing prosperity and participation in a global culture to the majority of Chinese after a long period of self-isolation.

Along with all the new Walkmans and VWs and McDonald's came foreign pop music, literature and Hollywood movies.

The appeal this had for the younger generation became evident in the early summer of 1989, when hundreds of thousands demanded democracy in Tiananmen Square.

In the years that followed, China's leadership re-calibrated globalization.

Goods, services and capital did continue to flow across borders.

But liberal thinking about freedom was to remain outside the borders.

Beijing cranked up its "patriotic" education efforts and mounted propaganda fueling distrust of anything foreign.

The Western idea that China might become more liberal through trade turned out to be wishful thinking.

In Germany, however, that belief continued to hold sway.

In part because it fit so well with the Germans' regulatory economic thinking, in which democracy and the market economy are essentially tied together.

"The globalization of the past two decades was a comfortable dream with an expiration date," says Max Zenglein, the chief economist at Merics, a Berlin-based think tank for China studies.

China was at the heart of globalization during that period.

"Anyone who still believes that there is no way around China today isn't thinking right," he says.

Now, he argues, it's time to wake up and build new plants – in countries like Vietnam or the Philippines, for example.

Xi Jinping's economic policies represent a harsh new zeitgeist.

In 2020, Xi announced a strategy of "two circuits" in response to the U.S.-China trade war.

What this means at its core is that China should no longer be dependent on foreign countries while at their same time preserving those countries' dependence on Beijing.

Accordingly, domestic consumption is to be increasingly served by domestic production to shield China from external shocks.

In foreign trade, China wants to make itself independent of technology imports, for example, by manufacturing semiconductors domestically.

As such, the country wants to transform itself from being the largest producer of finished products to the biggest maker of upstream products.

That doesn't bode well for the future.

If there were a massive geopolitical conflict and China were to become aggressive in its region, unlike Russia, it would be difficult to slap the country with sanctions.

Because by doing so, the West would cripple its own industry.

It's a painful realization: Economic integration alone can no longer steer world events in the right direction, either politically or morally.

This is also likely to be reflected in the new China strategy currently being formulated by the German government.

Sources within the government say that China will no longer be defined solely as the most important trading partner in the future, but also a systemic rival.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario