In Ukraine, Buying Time With Nuclear Concerns

Everyone understands how dangerous it is to fight near nuclear power plants, but that won’t stop Moscow or Kyiv from using it to their advantage.

By: Antonia Colibasanu

Fighting has escalated over the past few weeks near Zaporizhzhia, home to a Ukrainian nuclear power plant that has effectively been converted into a Russian military base.

It’s the largest nuclear plant on the Continent, and though only two of the six reactors are functioning, the International Atomic Energy Agency appealed for maximum military restraint in the area and has requested the safe passage of IAEA technicians to conduct safety, security and safeguards operations at the site.

On Aug. 19, French President Emmanuel Macron spoke with Russian President Vladimir Putin on the phone to discuss the situation, after which Putin reportedly agreed to send IAEA experts, albeit through Ukrainian territory, not Russian.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, having already spoke to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, pledged to discuss Zaporizhzhia with Putin as well.

It seems everyone is rightly worried about the chance of a nuclear accident.

Ukraine and Russia have accused each other of compromising the nuclear power plant.

In a press release, Putin accused the Ukrainian military of "systematic shelling" of the facility and said the attacks created the “danger of a large-scale catastrophe that could lead to radiation contamination of vast territories.”

Ukraine blames Moscow for deploying heavy weaponry on site.

Regardless of who is responsible, there is a broad understanding that the situation should not be taken lightly.

On Aug. 19, Russia reportedly told workers at the plant not to show up to work – without specifying when they can return.

Earlier in the week, Romania sent more than a million potassium iodide pills to Moldova to pre-empt possible radiation poisoning.

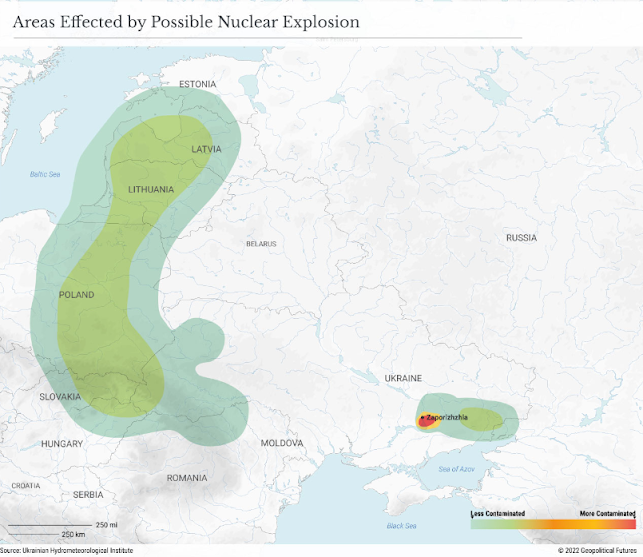

In addition to Moldova, reports suggest Romania, Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary could all be in the path of radioactive fallout.

Indeed, the consequences of an accident could be severe.

Though Zaporizhzhia’s two functioning reactors are well protected and, as such, are unlikely to be bombed directly, attacks on fuel storage sites or other infrastructure could release radioactive material which, according to expert reports, could travel several hundred miles, depending on the material's quality and density and on the vagaries of the wind.

In other words, the fallout could stretch well beyond Ukraine.

The concern is real, but the timing is odd. Reports about intensified fighting in the area near Zaporizhzhia came after reports of mysterious explosions Aug. 9 at the Saki air base in Crimea, which could mark a major shift in the war.

Satellite imagery shows that at least nine planes were destroyed in the explosions, and though Russia claimed it to be accidental, many believe it was an attack by Ukrainian forces.

(The government in Kyiv has yet to confirm as much.)

If Kyiv was indeed responsible, that means it is able to strike targets some 200 kilometers (125 miles) behind the front line – something Moscow had not expected.

Material damage aside, the attacks – if it was an attack – would devastate Russian morale and contravene Russian propaganda.

Notably, the explosions came one day after the United States promised to supply Ukraine with $1 billion worth of weapons.

As interesting, the reporting around Saki and Zaporizhzhia came as the war was more or less at a standstill.

After capturing Luhansk, the Russian army hasn’t gained more than 7 miles of ground along the 620-mile front between Kharkiv and Kherson in nearly a month and a half.

The Ukrainian counteroffensive to retake Kherson, meanwhile, has been going on for two months but has yet to retake the city.

U.S. weaponry, particularly the M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS), seems to have played a role in halting Russian operations.

Moscow has had to totally restructure its logistics to supply the men in the field, which has slowed its advances.

But Moscow had plenty of logistical problems before the HIMARS appeared, so it’s unclear whether its army will be able to resume its advance after it rebuilds its lines – or how effective it will be if it does – especially with even more U.S. weapons flooding into Ukraine.

Still, U.S. hardware can take Ukraine only so far.

Kyiv doesn’t quite have enough weaponry to retake areas such as Kherson, and even if it did, it doesn’t have the training or expertise to optimize the weapons it receives.

For example, Kyiv may have received long-range, high-precision missile systems from the U.S. and Great Britain in recent weeks, but it could manage only to incapacitate the major bridges over the Dnipro River near Kherson, forcing Russia to resort to ferries to transport its equipment.

For Ukraine, this is better than nothing, but it’s a far cry from being able to assault, subdue and control a city like Kherson.

All this means that, though both have been constrained in how much they can do for now, they are less limited in the long term – Ukraine with its new weapons and Russia with its reformed logistics and supply lines.

With no sign of a peace agreement in the works, both sides are unhappy with the status quo, and both would thus welcome disrupting the current stalemate in their favor.

This will result in one of two possibilities: a frozen conflict, which is bad for both sides, or an escalation, which neither wants right now, preferring instead to regroup and reorganize.

A nuclear accident – or the sheer prospect of one – would certainly give them the pause they are looking for.

Allowing nuclear experts to inspect the facilities at Zaporizhzhia wouldn’t advance the cause of long-term peace – if anything, it would only help Russia and Ukraine take a beat before gearing up for a subsequent round of fighting.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that the presence of third-party inspectors – if they manage to get in at all – will halt hostilities entirely.

But both Russia and Ukraine have an interest in buying time, and both understand how catastrophic a nuclear accident could be.

But that’s no comfort to them or to nearby residents who realize the obvious: that armed conflict around a nuclear power plant necessarily increases the chances that an accident will occur, no matter how sincere the belligerents are in avoiding one.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario