Chile Proposes a New Constitution

The post-Cold War era is ending, and changing eras call for new rules.

By: Allison Fedirka

On Sept. 4, Chileans will vote on a new constitution.

The referendum is the culmination of a three-year effort to write a new social contract that can address wealth inequality and political volatility.

But in a broader sense, it is part of a global transition from one era to the next.

It’s important to understand those larger forces at work, so that we can understand the possibilities and constraints for Chile as it moves forward.

The Making of a New Constitution

Latin American countries tend to have flexible relationships with their constitutions, to put it delicately.

Over a 205-year period (1810-2015), the 18 countries of Latin America enacted 195 constitutions, according to the Stockholm-based International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

This was especially true in the latter decades of the 20th century, when many governments transitioned from military to democratic control.

Constitutions in Latin America tend to be highly detailed, which also invites constant revisions or redrafting.

Chile, for example, introduced new constitutions in 1822, 1833, 1925 and 1980.

Santiago has amended the current constitution 52 times.

Brazil’s 1988 constitution has over 100 amendments.

But Chile’s constitutional rewrite didn’t come out of nowhere.

In October 2019, protests against an increase in metro fares in the capital got out of control.

Unrest spread to other cities, and the list of grievances swelled to include a range of perceived social and economic injustices.

After multiple attempts at dialogue, a state of emergency declaration and the deployment of the military, the government agreed to hold a referendum on whether to revise the country’s Pinochet-era constitution.

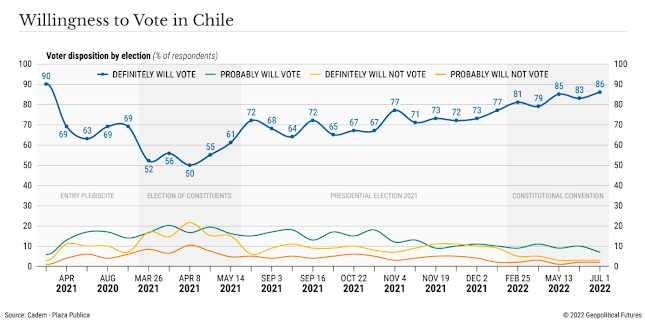

About half the registered electorate took part in the October 2020 vote, with 78 percent in support of a rewrite.

The following May, about 42 percent of registered voters turned out to vote for delegates to participate in the drafting.

They started their work in July 2021 and presented the final text on Monday.

A wider lens reveals more information.

Though geographically isolated, Chile suffers from the same wealth gaps and polarization as the rest of the region.

These features stem from Chile’s colonial past.

Colonial societies were extremely stratified, with wealth – typically from owning the country’s natural resources – concentrated at the top for generations.

These business interests and wealthy elites favor pro-market, right-leaning governments, while working-class voters tend to favor higher social spending advocated by left-leaning parties.

Meanwhile, systemic changes are underway.

During the Cold War, countries in “peripheral” regions (aka the Third World, or the Global South) chose sides – often due to coercion.

The Soviet Union’s breakup ushered in an era of democracy, laissez-faire economics and globalization.

Now the post-Cold War period is coming to a close.

What replaces it is still unclear.

Contents

The draft constitution is organized into seven sections, mostly focused on conventional issues, but with some parts directed at modern concerns.

A major criticism of the existing constitution is its emphasis on protecting private business at the expense of the public and the environment.

The draft document is intended to prioritize community rights, distribute power more broadly, protect the environment and indigenous groups, ensure gender equality (especially in government) and support state social services.

The committee charged with drafting the constitution also supported redefining Chile as a plurinational country, allowing for indigenous self-governance and greater participation of indigenous peoples in government.

Some analysts expected the new document to be a radical reform, but the committee’s makeup and approval process helped neutralize the effect.

Significant modifications were made in articles related to government models, mining and natural resources.

Government calls for a unicameral legislature – that is, a system with a single assembly – were rejected, though other amendments that weaken the role of the Senate were accepted.

On mining, a proposal to give the state exclusive rights over lithium, hydrocarbons and rare earth metals, as well as majority ownership in copper mines, was turned down.

The draft does, however, introduce new environmental restrictions to the industry, such as banning mining in glaciers, protected areas and regions essential to the water system.

Private rights over some water resources will also remain, though the draft constitution prohibits rights over glaciers and water resources in indigenous territories, and allows for government establishment of reserves in environmentally sensitive areas.

Looking Ahead

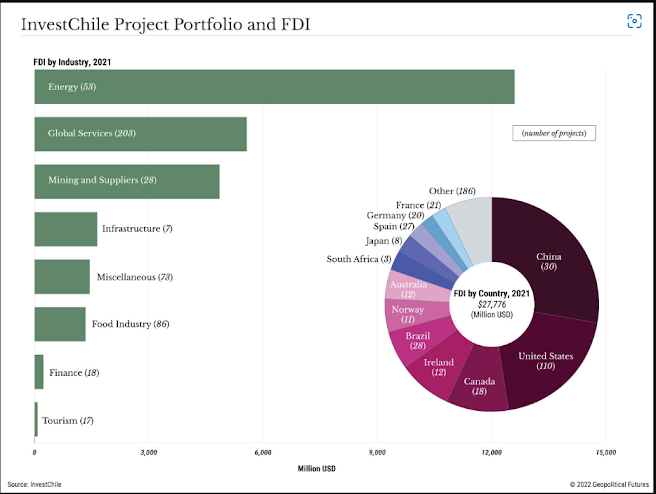

These compromises reflect the geographical and economic constraints facing Chile.

The country is physically isolated – by oceans, mountains and desert – from the rest of the world.

But extractive industries require huge investments that Chile can’t make on its own, meaning it must rely on outside investors.

The country’s relatively low population also means it doesn’t have enough domestic demand to match its potential output in the metals and agriculture sectors, forcing producers to look to external markets.

(Luckily, there’s plenty of appetite in the rest of the world for these types of goods.)

As a result, exports now account for nearly a third of Chile’s gross domestic product.

The country also relies on imports for its energy needs.

This reliance on external markets has acted as an incentive to maintain political and social stability.

And so, the need to attract investors will likely moderate whatever reforms are eventually passed.

The mining stipulations may introduce changes to existing contracts and the overall operating environment, but a complete overhaul could throw the entire Chilean economy into a tailspin at a time when it’s still recovering.

Some key changes should be expected, however: Chile’s government proposed tax reform plans, including modifications to the personal wealth tax and mining royalties, which would impact operating costs in the world’s top copper producer.

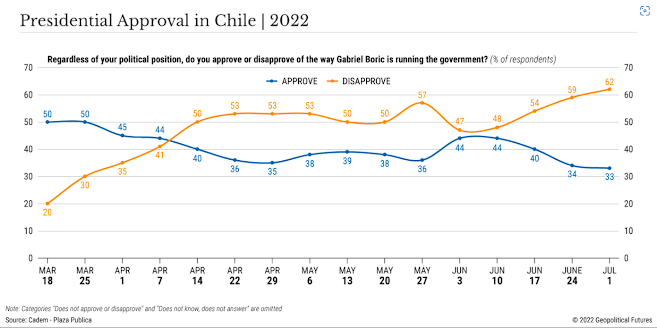

Chile’s current political climate reflects broader changes in the left-right political spectrum.

When Gabriel Boric won the presidency in December, there were concerns over what the election of a strong leftist president would mean for business.

That made sense considering that, during the Cold War and post-Cold War periods in Latin America, both the left and the right were highly ideologically driven and supported economic models that were often incompatible with economic progress.

However, Boric represents the emergence of a new left in Latin America – one that’s a product of the region’s political evolution, the pandemic and broader geopolitical shifts taking place globally.

It reflects a general disenchantment with traditional politics and a decoupling of economic models and ideology, and allows for more diversified international relationships.

In contrast to previous leftist models that emphasized populist politics, for example, Boric has argued that fiscal responsibility should be a state policy since it could help the government carry out needed reforms.

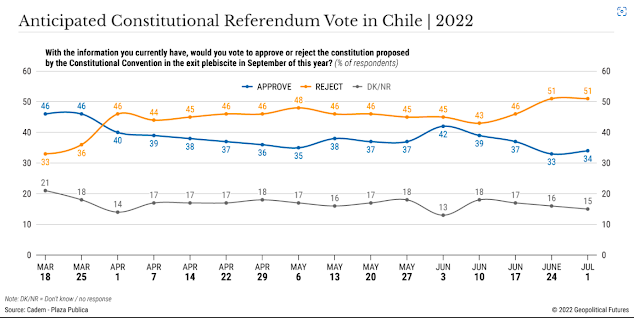

Voting in the upcoming referendum is mandatory, and passage will require support from at least 50 percent of the electorate.

It’s difficult to predict the result of the vote, though recent polls conducted by Cadem suggest that there will be a strong turnout and that just over a majority of the population plans to reject the new constitution.

But regardless of the result, Boric’s election win and the fact that a new constitution was put to a vote in the first place indicate a wind of change in Chile.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario