Russian menace brings abrupt end to the west’s ‘peace dividend’

In a reversal of the post-cold war era, Putin’s attack on Ukraine prompts Nato members to spend more on defence

John Paul Rathbone in London

“The prospect of a Soviet invasion of Europe is no longer a realistic threat,” George HW Bush proclaimed in 1991 as he announced a 25 per cent cut in US defence expenditure and Russia’s menace dwindled at the end of the cold war.

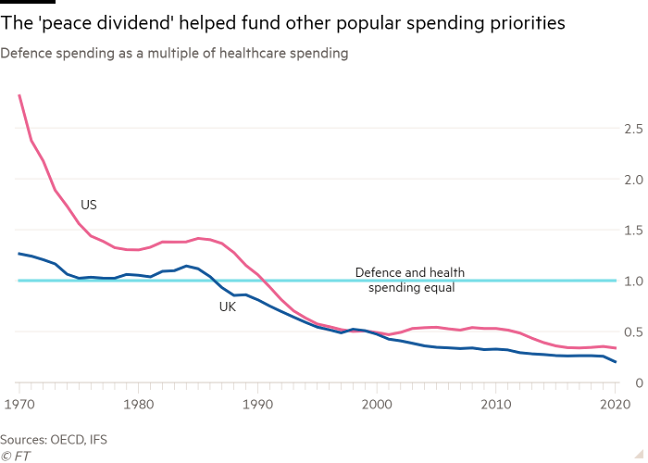

The then president’s comments signalled the optimistic era of the “peace dividend”. Western governments looked forward to funding priorities other than security, such as health and education or lower taxes, in a period of expanding free markets, liberal democracy and economic globalisation.

Three decades on, Russia’s assault on Ukraine has thrust defence spending up the agenda again.

The US is providing billions of dollars of military assistance to Kyiv.

Long complacent about defence, European countries including Germany have pledged to spend more.

“Now, whoomph, we are suddenly in a new era that is the opposite of globalisation, where statecraft and security concerns trump free markets and economics,” said Nigel Gould-Davies, senior fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a London think-tank.

But it is a re-prioritisation that could hurt western living standards.

As Kaja Kallas, prime minister of Estonia, which borders Russia, has said: “I would love to invest all this money that we invest in defence, in education, but . . . we don’t really have an option.”

Western military spending had already edged up by the mid-2010s, when Russia’s annexation of Crimea and support for eastern Ukraine’s separatist movements in 2014, plus fears about China’s rise, gave impetus to the US, UK and EU to repair security budgets cut after the 2008 financial crisis.

Military spending continued to rise slightly through the coronavirus pandemic, said Diego Lopes da Silva, senior researcher at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

But a complete reversal of the post-cold war peace dividend would be an expense on a totally different scale. It would also compete with other pressing needs, such as the transition to a green economy.

In the late 1980s, the US spent 6 per cent of gross domestic product on defence.

Last year, it spent 3.5 per cent, a difference worth more than $520bn.

EU countries cut back even further, in part because they relied on the US security umbrella and because rules limit their budget deficits and ability to raise debt.

Last year, among Nato’s 30 member states, only the US, UK, France, the Baltic states, Norway, Poland and Romania hit the alliance’s target of 2 per cent of GDP going on defence spending.

Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, spent just 1.3 per cent.

The invasion of Ukraine has shifted the calculus.

Although the west is now much stronger militarily than Russia, unlike in the cold war, Moscow’s unpredictability has prompted politicians to act.

Top of the list, analysts and defence officials say, are more combat-ready Nato forces positioned in states that border Russia, especially the Baltics, as well as increased force readiness and ammunition capacity.

A Ukrainian soldier carries a Javelin missile system. The US has sent an estimated one-third of its stock to Ukraine this year © Gleb Garanich/Reuters

A Ukrainian soldier carries a Javelin missile system. The US has sent an estimated one-third of its stock to Ukraine this year © Gleb Garanich/ReutersGermany’s army recently revealed it was short of combat-ready equipment.

Even the US, the world’s biggest defence spender, has been caught short: it has sent an estimated one-third of its Javelin anti-tank missiles to Ukraine, and replenishing that stock will take years.

“Just-in-time logistics are great — until you are in the middle of a battle,” said Andrew Graham, former head of the UK’s Defence Academy.

“Peacetime accounting doesn’t allow you to have reserves but military doctrine requires it.”

European pledges to raise defence spending are now flowing thick and fast, although how they will be funded is another matter: governments are having to help voters cope with surging food and energy costs that have been exacerbated by the Ukraine conflict.

“Central to Putin’s thinking is that the west will not cope and will eventually grow tired of supporting Ukraine,” a senior European intelligence official said.

Even in energy-rich Norway, which is profiting from rising oil prices, there are worries that Nato’s 2 per cent spending target is getting out of reach in an expanding economy.

In the UK, which is Nato’s second-biggest military spender, leading politicians are calling for defence budgets to rise to 3 per cent of GDP.

“I’ve always said that as the threat changes, so should funding,” said UK defence secretary Ben Wallace.

“It’s up to me to present a case about those threats.”

Germany has committed to reaching and even exceeding Nato’s target.

But the €100bn defence fund it is setting up will be enough to fund its spending gap for only two years, analysts estimate.

French president Emmanuel Macron has outlined plans to bolster military spending, but the country’s highest audit body has warned that, to do so, Paris will have to scrimp on other spending to hit budget deficit targets.

In Italy, Prime Minister Mario Draghi’s desire to increase defence spending has met public resistance, with teachers threatening protests and public transport workers announcing strikes.

And in Spain, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s goal of hitting the 2 per cent target by 2030 faces strong opposition from his government’s coalition partner.

Yolanda Díaz, the communist deputy prime minister, has said the priority should be “research, education and health”.

The Netherlands is a rare example where the government seems to have grasped the nettle.

Last week, it agreed to a series of spending increases to hit the 2 per cent target by 2024, paid for by tax rises, spending cuts elsewhere and public borrowing.

“2022 is the year when the importance of defence spending was recognised,” said John Llewellyn, former head of international forecasting at the OECD and partner at Llewelyn Consulting-Independent Economics.

“But it is not necessarily the year that the tax burden also had to rise to fund it.”

Additional reporting by Andy Bounds in Brussels, Guy Chazan in Berlin, Amy Kazmin in Rome, Richard Milne in Oslo, Sarah White in Paris and Peter Wise in Lisbon

https://www.ft.com/content/689fcff0-ada2-47d2-a576-882cd1af33b4

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario