Parity Is Unlikely to Be the Bottom for the Euro

Eurozone’s reliance on Russian gas and a closer examination of bond markets suggest there is little immediate upside for the single currency

By Jon Sindreu

The euro’s slide may not stop at a nice round number.

One euro now equals one U.S. dollar in wholesale financial markets.

“Parity” has been a staple of Wall Street forecasts for many years, yet it proved elusive until now: The common currency was created in 1999, and from 2002 it consistently traded above the greenback.

Dollar-euro is by far the most traded currency pair, representing 24% of all turnover in 2019, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

The euro also makes up 58% of the ICE Dollar Index, which weighs other currencies based on their relative importance in U.S. trade.

In a market portfolio of the world’s large-capitalization stocks, roughly 8% is in euros, MSCI data suggests.

Parity is an arbitrary but potent symbolic target.

There is a good chance that many hedges, options contracts and stop-loss orders have been structured to be triggered around this level on the assumption that it will act as a floor.

In today’s conditions, such expectations could turn out to be painful.

For one, market undercurrents aren’t as likely to engineer knee-jerk rebounds as in the past.

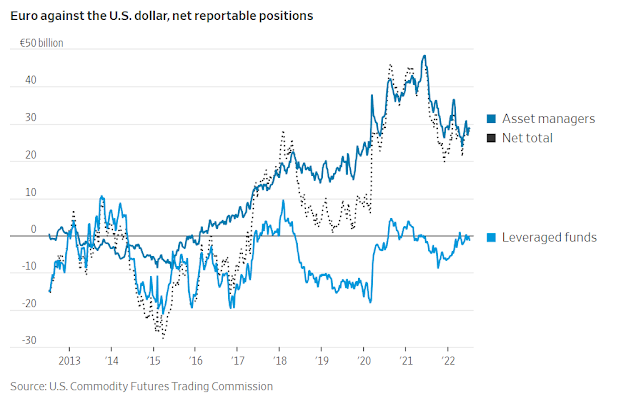

Ever since the Federal Reserve started raising rates in 2015, asset managers have leaned against dollar strength by buying the euro in derivatives markets, data by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission suggest.

Hedge funds have tended to take the other side.

In 2017, 2020 and to a smaller extent last year, they were forced to unwind these bets rapidly, fueling euro rallies.

But since then speculators have cleaned house: Their net dollar-euro bets are now small.

Interest rates play their role as well.

At the start of the year, the European Central Bank was much less hawkish than the Fed—one cause of the euro slide that started in June of last year.

Then eurozone officials signaled they would start playing catch-up, causing 10-year German bond yields to jump relative to those on Treasurys.

Many analysts foresaw the end of the euro’s woes.

But U.S.-style monetary policy in Europe seems unlikely in the longer term, given that the region’s economy has underperformed for a decade and now faces far greater dangers. Inflation-adjusted bonds are often used to gauge the “real” cost of credit.

Looking 10 years into the future but stripping out the first five, which serves to look through today’s fight against inflation, eurozone yields have risen to almost match U.S. ones.

This seems hard to justify and could reverse.

As a Bank of America analysis pointed out Tuesday, moves in longer-term German bonds may partly reflect factors other than rate expectations, such as higher volatility and uncertainty in an economy overshadowed by war.

Shorter-term maturities may be giving a more realistic picture of monetary policy: In recent weeks, it has become apparent that, rhetoric aside, the Fed is much more willing to act aggressively to combat inflation than the ECB.

As a result, the gap between two-year yields, which is key to explaining why hot money migrates from one region to another, has dropped back to a three-year low.

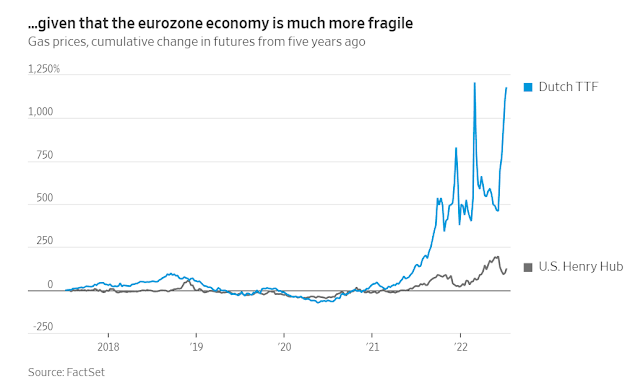

Ultimately, the main reason to expect further euro downside is that, whatever economic slowdown bond markets have moved to price in, it will almost certainly hit the single-currency bloc worse than the U.S.

JPMorgan analysts believe that recent euro exchange rates baked in no more than a 25% chance of Russian gas imports being cut off completely—a scenario that would likely cause a recession.

Pandemic cash transfers in Europe were smaller and less directed toward lower-income households, which makes the impact of high commodity prices more onerous.

Expensive energy and food have erased Germany’s trade surplus for the first time since 1991.

As a historical milestone, dollar-euro parity is a frivolous one.

Not so the energy crisis that triggered it.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario