Gradually Worse

By John Mauldin

This time last year, the great debate was whether inflation would

be “transitory.”

That question is now settled (Narrator: “It wasn’t transitory

at all.”), we have moved on to debating what the Federal Reserve will do about it… and can do about it.

The experts at the Strategic Investment Conference fell into two camps: The Fed will move either a) too fast and spark a deep recession, or b) too slow and let inflation get much worse.

(There’s a theoretical chance the Fed finds a perfect path in between, but I don’t know anyone who seriously expects it.)

That means we are heading somewhere unpleasant; the only question is what

kind of unpleasantry we’ll get.

My own opinion—admittedly in hindsight—is that inflation was already out of control before the debate even started.

The Fed should have resumed “normal” policy in late 2020 or early in 2021 as vaccines eased COVID effects.

They could have gone 25 points a meeting and backed off $10 billion of QE and normalized which would have given them some options.

They didn’t and now have no options but to lean into inflation.

Jerome Powell’s team kept emergency

measures in place long after the emergency (at least the economic part of it)

ended.

Powell knows recession is preferable to inflation (I’ll show why I believe this is true below), so I think he’s determined to err on the hawkish side—meaning a recession is coming soon.

I’ve also wondered whether negative market reaction would sway him, as it did in 2018.

Last week may have been a clue.

An unexpectedly strong Consumer Price Index generated a major sell-off in stocks and crypto assets.

Why?

Investors seem to fear the Fed won’t do enough to rein in inflation.

Then at this week’s FOMC meeting they decided to hike 75 basis points instead

of the previously expected 50.

So, this was a twist.

Powell gave the market what it wanted, but this time the market wanted tighter policy, not looser as it did in 2018.

We’ll never know whether he would have bucked Wall Street because (for once) Wall Street demanded the right thing.

He telegraphed the 75 basis point hike by a leak to Wall

Street Journal reporter Nick Timiraos, who has evidently replaced

John Hilsenrath as the new “Fed whisperer.”

While a few major banks called for the 75-basis-point hike the prior week, all the majors piled on following that report.

The market priced in

the full 75-basis-point hike almost immediately, giving Powell permission to do

what he wanted to do anyway.

Unfortunately, I think everyone is too late.

I believe significant inflation is probably locked in for the next year at least.

It will come in

waves of varying intensity, as happened in the 1970s, but the overall trend is

set.

Today we’ll look at some evidence this period could even be worse than the 1970s.

Then we’ll read the mea culpa regrets of someone who had a big part in that drama.

We Need Volcker-Plus

Throughout this period, we’ve seen a steady stream of 1970s comparisons.

Usually they show today’s statistics, while bad, aren’t as bad as they were back then.

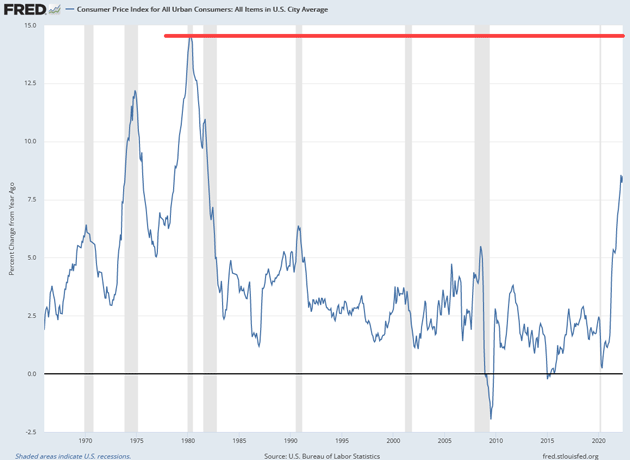

Here is the year-over-year change in CPI since 1966.

You

can see from the red line that 2022 inflation is still far below that peak, at

least officially.

Source: FRED

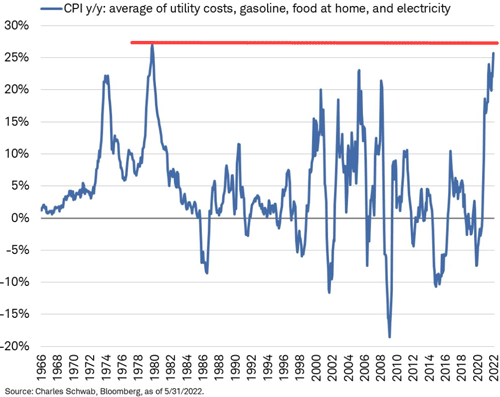

That’s good news, but CPI doesn’t hit everyone equally.

Here’s a

chart we sent Over My

Shoulder members last week, showing the average CPI change for

four categories a typical household has little ability to control: utilities,

gasoline, food at home, and electricity.

Source: Over My

Shoulder

That red line shows today is uncomfortably close to late 1970s-level misery.

And, as we’ll see below,

there’s no reason to expect improvement anytime soon.

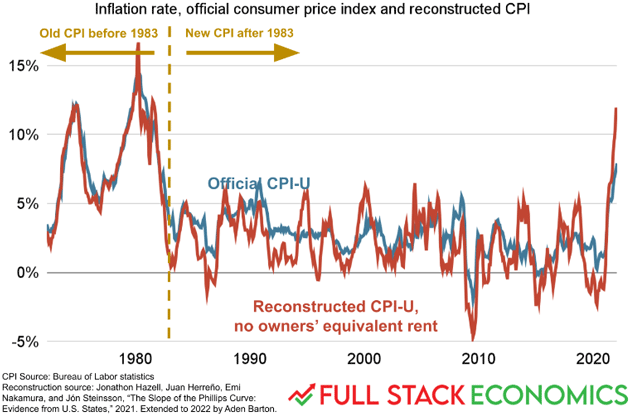

Larry Summers, one of the few prominent economists to see this inflation coming, recently co-authored a paper that finds today’s inflation is already closer to 1970s-level than most people think, if you make a proper apples-to-apples comparison.

The difference lies mainly in the way CPI accounts for housing

costs.

I have written many times about the 1983 introduction of “Owner’s Equivalent Rent” instead of actual home prices or mortgage payments.

There were good reasons for that change, but it makes comparisons difficult for years before and after 1983.

The index methodologies are significantly different.

Summers argues that the change means pre-1983 CPI figures, had they used OER to measure housing prices back then, would be lower than they now look.

You can read the full paper for details, but here’s the key point.

“Our analysis reveals that current inflation, especially core inflation, is considerably closer to previous peaks than in the official series.

Official core CPI inflation peaked at 13.6 percent in June 1980, whereas we estimate that core inflation was 9.1 percent in that same month when adjusting for the treatment of shelter inflation.

Our estimates

also suggest that the local trough of core CPI inflation in 1983 was

considerably higher than originally reported.

“Overall, these estimates imply that the rate of core CPI disinflation caused by Volcker-era policies is significantly lower when measured using the current treatment of housing: only 5 percentage points of decline instead of 11 percentage points in the official CPI statistics.

To return to 2 percent core CPI today, we thus need

disinflation of a similar magnitude as Chairman Volcker achieved.”

That’s a lot to unpack with staggering implications if correct, which I think it is.

It means Volcker’s aggressive rate hikes accomplished less than thought.

That, in turn, implies today’s Fed will have to tighten even more than Volcker did to

get the same effect on inflation.

Last month we sent Over My Shoulder members another paper on why the government took home prices out of its main inflation index.

They made a similar calculation (which Summers cites as confirmation, by the way), finding CPI since 1983 would have averaged 2.2% without the OER change, instead of 2.7%.

That small variance adds

up when compounded over 39 years.

Source: Over My

Shoulder

In this chart, you can think of the red line as what CPI would be without the OER change.

It was both lower over the full period and quite a bit higher now.

The chart ends at February 2022 and the subsequent difference seems

likely even greater.

Today’s Fed is certainly not where Volcker was in policy terms.

This week Powell turned slightly more hawkish.

But come on—he is a long way from doling out the kind of harsh medicine Volcker did.

Maybe he hopes it won’t be necessary.

If so, we’d all better hope he is right.

Biting the Bullet

Another parallel with the 1970s is the contribution energy prices make to inflation.

And in both cases, a war served to trigger it.

George Friedman had a reminder just last week.

Going into October 1973, inflation was already a serious problem.

Nixon had imposed a wage and price freeze and closed the gold window.

Unemployment was rising rapidly.

Then the other shoe

fell.

“In October 1973, with Nixon wallowing in the Watergate scandal, Egypt and Syria caught Israel by surprise in a stunning and unexpected attack.

The U.S. held back from supporting Israel, but as Israel started to run out of artillery shells and other necessities, the U.S. began to airlift supplies in.

Arab oil producers responded by placing an

oil embargo on the United States and Israel’s other supporters, particularly in

Europe.

“It was a stunning blow to the U.S. economy, where oil prices not only rose but oil became unavailable.

Gas stations that had fuel had lines of cars a half mile lined up.

Oil was an essential commodity, and it was unavailable.

Inflation surged. Unemployment soared as businesses closed. Interest rates rose as banks protected reserves.

The oil embargo continued for months among some producers.

It’s not excessive

to say that the American and other economies were heading toward meltdown.”

This has some parallels with 2022.

Energy prices and inflation were already rising before Russia attacked Ukraine.

Like the Arab Israeli War, the Ukraine War intensified prior trends.

There is a key difference, though.

In 1973 the Arab countries refused to sell oil to the US and its allies.

In 2022, the US and its allies, while not fully boycotting (yet), are trying to drastically reduce what they buy from Russia.

But the result is the same: higher energy prices for consumers almost everywhere.

This feeds through to other prices, raising inflation.

We are in somewhat better shape this time around because the US has much more domestic production capacity.

We also have significant renewable energy sources.

But relative to demand, they still aren’t enough, and we have few ways to quickly increase supply.

This means any price relief will have to

come from reduced demand.

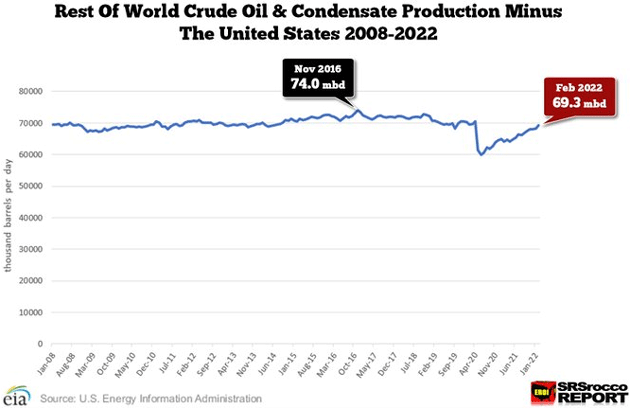

The global supply situation is actually worse than you think.

Non-US world production is 4.7 million barrels per day less than six years ago, and basically flat for the last 14 years.

This means reduced prices anytime soon

will require even more demand destruction.

Source: SRSrocco

Falling demand is not yet evident at airports or on the highways.

The opposite seems more common: People are eager to travel after two years of COVID.

This may change, though.

Vacation and convention travel is typically planned well ahead of time.

If fuel costs make the trip a little more expensive, most people will bite the bullet and go.

But they may hesitate to

plan the next one, meaning we could see a slowdown later.

The Federal Reserve would like to see that effect, and others like it, happen sooner.

Its main weapon is to swing a large blunt object (higher interest rates) in all directions.

This, the theory goes, will reduce liquidity and cause businesses and consumers to reduce demand for goods and services.

Prices will then fall.

The theory works but not rapidly.

Higher interest rates first affect the most highly leveraged sectors, two of which are stocks and housing.

In stocks it is mostly indirect: Higher rates make fixed income assets relatively more attractive, reducing demand for stocks, whose prices then fall.

This has a reverse “wealth effect” as stockholders see their net worth decline

and become less likely to buy other things.

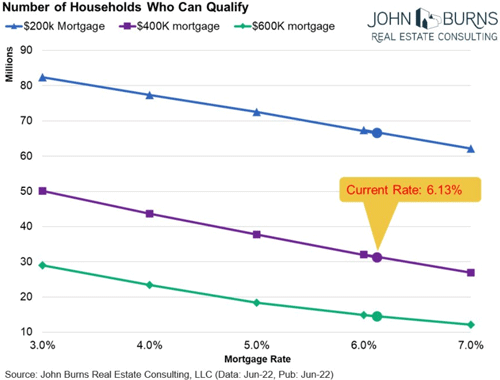

As for housing, higher mortgage rates are already pinching demand.

John Burns’ team calculates that the increase since January from 3% to over 6% now means 18 million fewer households can qualify for a $400,000 mortgage.

That’s a 36% reduction in potential demand.

Source: Eric Finnigan, JBREC

Here again, this is what the Fed wants.

They don’t have to kill the housing boom (nor should they) but letting some air out of the balloon will reduce demand for skilled construction labor, building materials, and the myriad things people buy when they move into a new house.

That should help bring down

CPI.

That balloon metaphor raises another question.

Is it better to let the air out slowly, or just pop it?

Paul Volcker pulled out the big needle.

Anguish All Around: Against

Gradualism

Arthur Burns was Federal Reserve chair from 1970‒1978.

He had previously been an academic economist and was an economic advisor to Richard Nixon, who then appointed him to the Fed.

Inflation was already high when Burns

took the chair and got considerably worse.

All that’s well known.

What I didn’t know, until my friend Brent Donnelly told the story recently, is that Burns made a rather dramatic (at least looking at it now) mea culpa speech in September 1979.

He had left the Fed 18 months earlier.

His successor G. William Miller didn’t last long and Jimmy Carter had just

replaced Miller with Paul Volcker.

Volcker wasted little time, further raising rates that were already in double-digit territory.

Burns apparently wished he had done the same—and said as much in the speech.

He seemed to agree central bankers hadn’t done

their jobs.

“By training, if not also by temperament, they are inclined to lay great stress on price stability, and their abhorrence of inflation is continually reinforced by contacts with one another and with like minded members of the private financial community.

And yet, despite their antipathy to inflation and the powerful weapons they could wield against it, central bankers have failed so utterly in this mission in recent years.

In this paradox lies the anguish of central banking.”

At the same time, Burns also blamed the American public’s expectation the government would ensure prosperity and growth.

He described it going back to the 1930s and then more in the 1960s.

He discussed how this led

to the inflation he had faced at the Fed.

“Many results of this interaction of government and citizen activism proved wholesome.

Their cumulative effect, however, was to impart a strong inflationary bias to the American economy.

The proliferation of government programs led to progressively higher tax burdens on both individuals and corporations.

Even so, the willingness of government to levy taxes fell distinctly short of its propensity to spend.

Since 1950 the federal budget has been in balance in only five years.

Since 1970 a deficit has occurred in every year.

Not only that, but the deficits have been mounting in

size.

“Budget deficits have thus become a chronic condition of federal finance; they have been incurred when business conditions were poor and also when business was booming.

But when the government runs a budget deficit, it pumps more money into the pocketbooks of people than it withdraws from their pocketbooks; the demand for goods and services therefore tends to increase all around.

That is the way the inflation that has been

raging since the mid-1960s first got started and later kept being nourished.”

He then seemed to offer Volcker some advice.

“Viewed in the abstract, the Federal Reserve System had the power to abort the inflation at its incipient stage fifteen years ago or at any later point, and it has the power to end it today.

At any time within that period, it could have restricted the money supply and created sufficient strains in financial and industrial markets to terminate inflation with little delay.

It did not do so because the Federal

Reserve was itself caught up in the philosophic and political currents that

were transforming American life and culture…

“My conclusion that it is illusory

to expect central banks to put an end to the inflation that now afflicts the

industrial democracies does not mean that central banks are incapable of

stabilizing actions; it simply means that their practical capacity for curbing

an inflation that is continually driven by political forces is very limited…

“The present widespread concern

about inflation in the United States is an encouraging development, but no one

can yet be sure how far it will go or how lasting it will prove. The changes

that have thus far occurred in fiscal, monetary, and structural policies have

been marginal adjustments.”

And here is the money shot:

“American policymakers tend to see merit in a gradualist approach because it promises a return to general price stability—perhaps with a delay of five or more years but without requiring significant sacrifices on the part of workers or their employers.

But the very caution that leads politically to a policy of

gradualism may well lead also to its premature suspension or abandonment in

actual practice.

“Economic life is subject to all sorts of surprises and disturbances—business recessions, labor unrest, foreign troubles, monopolistic shocks, elections, and governmental upsets.

One or another such development, especially a business recession, could readily overwhelm and topple a gradualist timetable for curbing inflation.

That has

happened in the past and it may happen again.”

You can read the entire speech but I think this is the critical part.

We can’t know exactly why Burns said this.

Maybe he thought Volcker was going to abandon gradualism anyway.

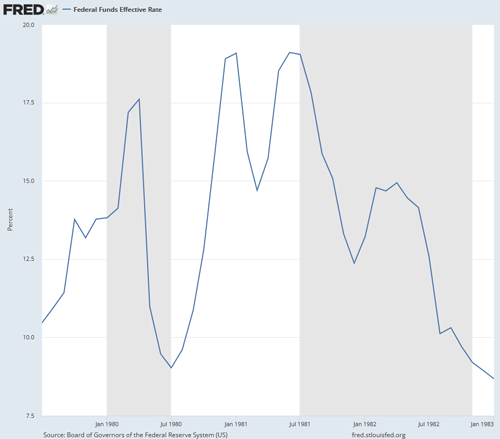

Here’s a chart of the federal funds rate in

Volcker’s first term.

Source: FRED

Note those near-vertical lines.

These 50‒75 basis point moves people now consider “aggressive” are mild in comparison.

The Volcker Fed had multiple hikes of 100 bps or more.

Volcker rewarded Jimmy Carter’s appointment by giving him an immediate recession going into 1980.

Then they took fed funds

1,000 points higher in the second half of 1980, helping cost Carter the

election and welcoming Ronald Reagan with an even deeper recession.

Volcker and his FOMC made no pretense of acting gradually.

They did what they thought was necessary, generating enormous pain but finally stamping out inflation.

I hope Jerome Powell will find his inner Volcker.

This week’s 75-basis-point hike—widely portrayed as “aggressive”—was far short of the mark.

Powell is practicing the very “gradualism” Arthur Burns did, and

which he later admitted was a mistake.

This means, unfortunately, taming inflation will be difficult, and the Fed will have to clamp down even harder.

Would we be better off with a Volcker-style rapid rise that kills demand across the economy?

Or getting the recession gradually?

I’m sure the Fed staff is telling the FOMC members they can get CPI and PCE back down without imposing such pain.

I’m equally sure they have models showing this.

We are going to find out if they’re right.

Family and Home Again

It was wonderful to have my daughter Tiffani and granddaughter Lively visit us last weekend.

I went on the same plane with them to Miami, and we were able to get Lively upgraded to sit next to Papa John.

That was fun. I

then got a workout going from Miami airport’s gate D60 to D1 in 30 minutes.

In Dallas, I was kidnapped by Jay Young and his team from King Oil and taken to a ground-level suite right behind home plate for the Rangers-Astros game.

Literally the ground was at my seated eye level.

Home plate was 30 feet away.

A far cry from when I had an office in right field at the old ballpark.

Thirty feet is a lot closer than 500.

It was a fabulous

experience.

The next day was a real education on the oil business.

I am

relatively bullish on the oil complex, as you may have guessed.

Weekend after next, Shane and I will celebrate five years of marriage and also her birthday.

We cleverly combined the two so I would remember at least one.

And shortly after that Amanda and Abigail and three of

my granddaughters come visit us for a few days (along with their husbands),

which we are really looking forward to.

And with that, let me hit the send button.

I wish you a great

week. And don’t forget to follow me on Twitter.

Your thinking how inflation really will turn out analyst,

|

|

John

Mauldin |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario