India’s Defiance of Washington’s Russia Strategy

New Delhi has resisted calls to stop doing business with the Russian economy.

By: Allison Fedirka

Under normal circumstances, India would have little reason to care about what happens in Ukraine.

The current circumstances, however, are far from normal.

The war in Ukraine has put U.S.-Indian relations back into the spotlight as Washington lobbies all of its major allies to join its economic assault on Moscow.

So far, India has resisted.

The U.S. wants to use the Ukraine conflict to bring India into alignment with the West on issues that don’t relate to China, but New Delhi is unwilling to impose its own sanctions on Russia and recently even agreed to purchase millions of barrels of Russian oil.

Its defiance is important less because of India’s ability to prop up the Russian economy and more because of what it says about the state of U.S.-Indian relations.

Still, strategic constraints will compel Washington not to take punitive measures against New Delhi for its noncompliance and to seek mutually acceptable accommodation instead.

Difficult to Manage

Alliances derive their strength from shared interests among members.

For the U.S. and India, their mutual desire to contain Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific is the cornerstone of their partnership.

But their lack of alignment on other issues can make it difficult to manage.

For India, formalizing military or political alignments is seen as risky because the country fears that doing so could make it vulnerable.

For much of India’s modern history, the sub-continent fell under the control of a foreign power.

Today, the country finds itself between three major powers (Russia, China and the U.S.) and sharing borders with two formidable enemies (Pakistan and China) – all while trying to find its place as a major player in its own right within the region.

And while New Delhi agrees on the importance of containing China, the U.S. and India’s distinct geographies, histories and economics result in diverging interests over secondary issues.

The Ukraine matter is a case in point.

For the U.S., the Russian threat didn’t end with the Cold War, and a Russian victory in Ukraine would mean a win over the West.

But India sees Russia as much less of a threat than the U.S. does.

During the Cold War, Russia was a reliable trade and defense partner for India and helped keep China in check.

New Delhi has a pragmatic approach to foreign relations and has managed to maintain ties with various partners without fully committing to any single one.

It thus has cultivated good relations with Moscow while attempting to strengthen ties with the U.S. of late – and it’s unwilling to veer too far away from this balance.

But the war in Ukraine has complicated India’s position.

The U.S. fears that India’s continued willingness to do business with Russia could undermine the U.S. strategy to force Moscow into concessions through economic isolation.

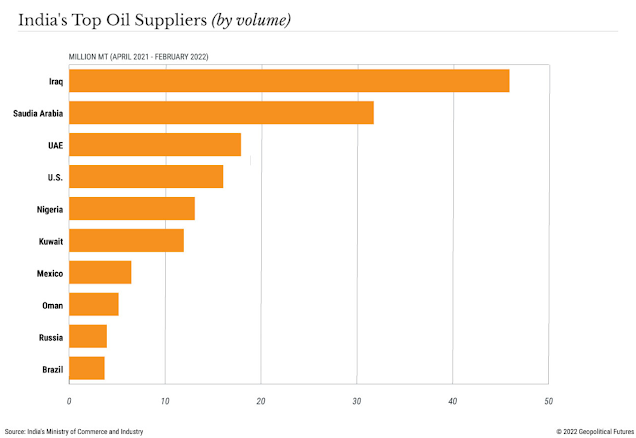

India’s noncompliance can best be seen through its energy sector.

Since the start of the invasion, India has been on a spending spree, buying up Russian oil at a discounted price compared to international markets.

India has ordered an estimated 13 million to 14 million barrels of oil from Russia since the end of February, compared to the 16 million barrels it purchased from Russia all of last year.

As the world’s third-largest oil importer, India relies on foreign supplies to meet approximately 80 percent of its needs.

Though Russia supplies only 1-2 percent of the oil consumed in India, the main attraction at the moment is the low price – a key consideration given that India spent approximately $100 billion on oil imports in the last fiscal year.

Under the current terms, Indian imports of Russian oil don’t violate U.S. sanctions, but Washington fears New Delhi’s continued purchases of Russian exports could prove to be an economic lifeline for Moscow.

India has had similar problems with other energy suppliers in the past.

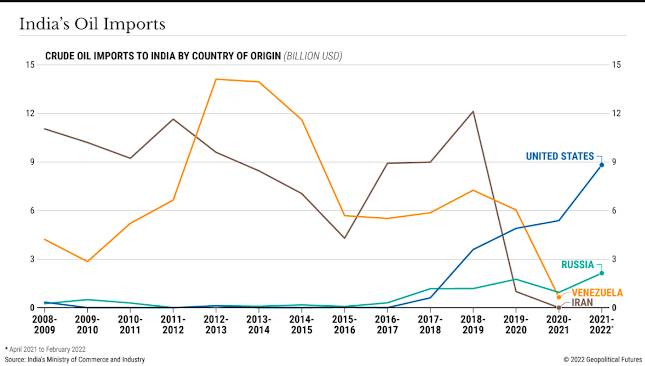

Iran and Venezuela together accounted for 20 percent of India’s oil imports in 2016, but were both subject to U.S. sanctions in recent years.

In these cases, however, Washington issued waivers that allowed India to continue importing from these countries during a transition period and increased its own energy exports to help fill the gap.

The U.S. has told India that it will help support its efforts to diversify its suppliers again, but that could prove more difficult this time around.

The U.S. government is currently using its strategic reserves to boost its own domestic supplies, and private companies have resisted Washington's calls to increase production.

Washington’s urging of Saudi Arabia to increase production hasn’t worked either.

And the U.S. has already committed to helping European markets find alternative sources, so whatever supplies it’s able to export will need to be shared among all its partners.

To a lesser extent, the U.S. has also taken issue with India’s purchases of Russian fertilizers and defense equipment.

Russia is one of the largest global suppliers of fertilizers, which are exempt from U.S. sanctions because of a global shortage and their importance in food production.

Prior to its invasion of Ukraine, Russia banned the export of fertilizers through the end of June and limited the countries to which its supplies could be sent.

India is among the approved destinations – though it received only 8.5 percent of its fertilizer imports by value from Russia in 2020.

Washington had concerns over India’s procurement of Russian defense equipment even before the war in Ukraine began.

During the Soviet era, India acquired much of its military equipment from the USSR.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Russia is still India’s top arms supplier, accounting for just under half of all arms imports.

But this figure is down from 69 percent between 2012 and 2017, as Russia’s share in India’s arms imports has steadily declined over the past decade.

That’s in part because India is developing a national defense industry initiative, which will increase its self-sufficiency in arms, and recently announced it would stop importing over 100 defense-related goods from Russia by the end of this year.

Notably, the U.S. has not applied the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act to India since its introduction in 2017.

Under the act, any country that signs defense deals with Russia, Iran or North Korea may be subject to sanctions.

Levers and Constraints

The U.S. does have some economic levers it can use to influence India’s behavior.

Trade between the two countries totaled $113.4 billion in 2021 – one-third U.S. exports to India and two-thirds U.S. imports from India – making the United States India’s largest trade partner.

Exports to the U.S. account for 18.9 percent of India’s total exports and the equivalent of 3.5 percent of gross domestic product.

The U.S. is also a major contributor of foreign direct investment, spending roughly $41 billion in India in 2020.

In 2021, it ranked as India’s second-largest source of FDI behind Singapore.

The services sector was the top beneficiary (16 percent), which includes outsourcing, R&D and tech testing.

This was followed by computer software and hardware, which receives 14 percent of total FDI.

For India, technology remains a top priority for trade and FDI as many of the government’s economic development initiatives rely on getting access to or funding for technology from places like the U.S. and the EU.

However, the U.S. faces three strategic constraints that prevent it from bringing its full economic power to bear on India.

First, its Indo-Pacific strategy for containing China requires India’s participation.

And given that the U.S.-China rivalry will likely remain for years to come, Washington needs New Delhi on its side in the long term.

Second, it’s in the U.S.’ interest to maintain a relatively stable and functional India to counter China.

Imposing economic punishments for India’s unwillingness to toe the line on Russia could be destabilizing for New Delhi, and that would only benefit Beijing.

Last, India plays an important role in the foreign policies of the U.K. and Australia – the former of which is relying on commonwealth states to boost trade to offset the economic losses from leaving the EU.

Australia, meanwhile, signed an interim free trade agreement with India earlier this month.

The pact, which covers over 90 percent of goods traded between the two countries, is part of Australia’s strategy to reduce its dependence on China.

The U.S. wouldn’t want to do anything to weaken these relationships with India, especially because the U.K. and Australia are both members of the Five Eyes, Washington’s most important security alliance.

When it comes to trade with Russia, there’s plenty of space for the U.S. and India to find mutually acceptable accommodation.

New Delhi has shown that it’s willing to work toward self-sufficiency in the defense sector, meaning its purchases of Russian military goods will diminish over time – although this will likely be a long process.

Besides, Washington has already given New Delhi some leeway here by not imposing sanctions over its Russian arms purchases.

India’s other main imports from Russia are fairly low and focus on strategic sectors essential to keeping the Indian economy running – i.e., fertilizers and energy.

As long as this remains the case, the U.S. will tolerate the limited commercial exchange between India and Russia.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario