The Odds Don’t Favor the Fed’s Soft Landing

Inflation is higher, the labor market tighter and real rates more negative than in past periods when the Fed raised rates without causing a recession

By Greg Ip

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell at an economic conference on Monday in Washington. / PHOTO: SAMUEL CORUM/GETTY IMAGES

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell at an economic conference on Monday in Washington. / PHOTO: SAMUEL CORUM/GETTY IMAGESFederal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell explained this week what he and his colleagues hoped to accomplish with the interest-rate increases they initiated last week.

“The economy achieves a soft landing, with inflation coming down and unemployment holding steady,” he told a conference of economists.

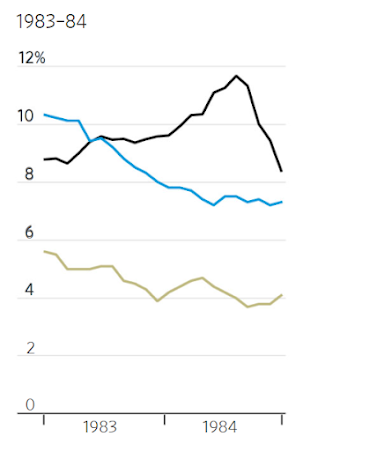

In 1965, 1984 and 1994, the Fed raised interest rates enough to cool an overheating economy without precipitating recession, he noted, adding it may have done the same in 2019 but for the Covid-19 pandemic.

Unfortunately, history isn’t on his side. Inflation is much further from the Fed’s objective, and the labor market, by many measures, is tighter than in previous soft landings.

Yet the Fed starts with real interest rates—nominal rates adjusted for inflation—much lower, in fact deeply negative.

In other words, not only is the economy already traveling above the speed limit, the Fed has the gas pedal pressed to the floor.

The odds are that getting inflation back to the Fed’s 2% target will require much higher interest rates and greater risk of recession than the Fed or markets now anticipate.

The biggest contrast with prior soft landings was that in the past, the Fed sought only to keep inflation from going up—not to actually push it down.

Today, though, it starts with core inflation, which excludes food and energy, above 5% using the Fed’s preferred price index, more than 3 percentage points above target.

History and the Fed’s own models are pretty clear: When inflation is too high, pushing it down requires damping demand and pushing up unemployment so that workers and firms must settle for lower pay and prices.

Yet the median projections released by Fed officials show no such thing: They anticipate core inflation falling to 4.1% at the end of this year, 2.6% next year, and 2.3% in 2024 while unemployment stays near a 50-year low of 3.5% to 3.6% for the entire period.

Higher interest rates may reduce demand, such as the waiting lists for new cars. / PHOTO: MARIO TAMA/GETTY IMAGES

Higher interest rates may reduce demand, such as the waiting lists for new cars. / PHOTO: MARIO TAMA/GETTY IMAGESUntil last fall, such an “immaculate disinflation” seemed plausible as supply-chain disruptions eased and prices of durable goods, especially cars, fell from elevated levels.

But progress on supply chains has been swamped by fresh disruptions from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Covid-19 restrictions in China.

Meanwhile, inflation has spread well beyond durables to a wider range of goods and services.

Suppose goods inflation drops to its pre-pandemic rate of around zero.

If services inflation continues at its recent pace, overall inflation will stay above 3%.

Supply disruptions, such as in oil markets, had only transitory impacts on inflation in the 1990s and 2000s because the public expected inflation to return to around 2% and set wages and prices accordingly.

The Fed expects the same this time, noting bond markets and surveys show expectations for inflation five to 10 years from now are still close to 2%.

But supply disruptions have been bigger, broader and longer lasting than in the past, and bond investors now expect inflation to stay above 3% through 2024.

Higher expected inflation makes it harder to get actual inflation down and blunts the impact of the Fed’s monetary tightening.

Since December, bond yields have risen sharply but so has expected inflation, so real yields are still deeply negative.

Fed officials project their federal-funds rate target will peak at 2.8% next year.

If inflation is above 3%, that is a negative real rate.

Negative real rates are necessary for a weak economy in need of stimulus, but today’s is just the opposite.

Unemployment is 3.8%, lower than at the start of any Fed tightening cycle in 70 years except 1969 (which ended in recession). It is also below Fed officials’ 4% estimate of the “natural” unemployment rate, below which price and wage pressures build.

Moreover, for three years they see unemployment persisting below 4% and the economy exceeding its long-term potential growth rate of 1.8%.

True, the natural unemployment rate and potential growth are impossible to observe directly and the Fed has gotten them wrong in the past.

Still, with job vacancies at a record and wages rising briskly, it is a good bet unemployment is below, not above, its natural rate today.

In fairness, there are several unusual features to today’s economy that support the case for a soft landing.

Unlike in the past, high inflation now results from strong demand interacting with constrained supply.

Higher interest rates may reduce demand, such as the number of bidders per house or the waiting list for new cars, thereby reducing prices but not the number of houses and cars sold.

Job openings are 70% higher than the number of unemployed.

Reduced demand for labor could mean the same number of workers get hired but at lower wages than otherwise.

Second, the labor force shrank during the pandemic due to early retirements, child-care issues and Covid-19.

As the pandemic recedes, the Fed expects the labor force to bounce back, allowing employment and output to grow briskly without pushing unemployment down further or putting upward pressure on wages.

Still, history doesn’t provide much precedent for those things.

If they don’t pan out, and supply chains don’t swiftly normalize, then the Fed will likely have to accept higher inflation—which Mr. Powell said isn’t in the cards—or raise interest rates until unemployment rises.

In theory, that can happen without a recession.

That, too, would be unprecedented.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario