Syria Mulls Pulling Out of Iran’s Orbit

Assad is enlisting Abu Dhabi’s help in curtailing Iranian influence in his country.

By: Hilal Khashan

Last week, Syrian President Bashar Assad visited the United Arab Emirates, his first foreign trip since the Syrian uprising in 2011.

The U.S. State Department issued a stern statement taking issue with the attempt to legitimize Assad’s rule, given the horrendous crimes he committed in a war that has killed more than 500,000 Syrians and has left 150,000 missing.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the U.S. rejects efforts to rehabilitate Assad and his regime.

But the trip followed years of normalization efforts between Arab countries and the Syrian government.

Throughout the war, several Arab states maintained diplomatic ties with Syria, others resumed them in 2013, and still others cooperated on security matters.

In welcoming Assad, Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Zayed described Syria as an essential cornerstone of Arab security.

After their meeting, the two leaders issued a joint statement that called for the withdrawal of foreign forces from Syria, the preservation of its territorial integrity, and a peaceful end to the conflict.

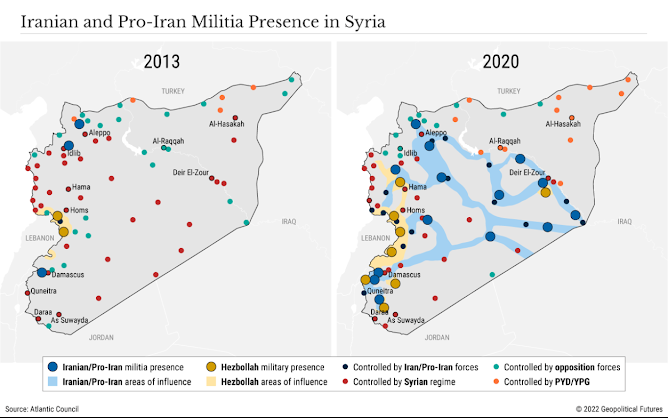

But for Assad, one of the top goals of the visit was to enlist Abu Dhabi’s support in curbing Iran’s influence in Syria, marking a policy shift that Washington will likely support.

Western Disinterest in Syria

The hope that the Syrian uprising would quickly unseat Assad was short-lived.

After Assad successfully portrayed his repressive policies as a war on terrorism, interest in the Syrian conflict dwindled.

In 2012, former French President Nicolas Sarkozy launched the Friends of Syria Group after Russia and China vetoed a U.N. Security Council resolution to condemn the atrocities committed by the Syrian regime against demonstrators demanding freedom.

Conferences organized by the group in 2012 included representatives from 70 countries and numerous international and regional organizations.

By 2013, only 11 countries participated in the gatherings, which were suspended shortly thereafter.

It was a sign of the West’s increasing disinterest in the conflict.

In 2013, when the Assad regime used nerve gas to kill 1,429 Syrians, including 426 children, the British Parliament voted against military action.

U.S. public opinion also opposed strikes against the regime, and President Barack Obama decided against intervention.

The rationale for not punishing Assad was that the U.S. had no vital interest in Syria.

Similarly, Washington hasn’t taken any punitive measures against Arab countries that have normalized relations with Damascus.

Though the State Department said the U.S. doesn’t encourage reestablishing diplomatic ties with the Assad regime, it accepts that Arab countries can choose their own paths forward.

The U.S. opposes the Syrian regime’s reintegration into the Arab order, but only in principle.

It also hasn’t ruled out working with Assad when peace in Syria is restored.

The U.S. made it clear only that it would not lift sanctions on the Syrian government or contribute to Syria’s reconstruction before the Assad regime reaches a political agreement with opposition groups on a post-conflict political system.

Abu Dhabi’s Motive

In 2011, the Arab League suspended Syria’s membership in the group as many Arab countries severed their diplomatic ties with the Assad government.

But Assad’s derailing of the peaceful Syrian uprising actually served Arab authoritarianism well.

He transformed Syria into a theater for sectarian conflict and geopolitical struggle, and gave Arab rulers the ability to suppress uprisings in their own countries, presenting the cost of change as too great to bear and a choice between stability and bloodshed.

Normalization became possible only after authoritarian Arab leaders defeated uprisings in their countries and sabotaged demands for a transition to democracy.

Abu Dhabi filled the void left by Washington’s disinterest in the conflict, especially after Obama did not oppose Russian military involvement in the civil war.

In 2018, the UAE reopened an embassy in Damascus, which encouraged several other Arab countries such as Jordan and Bahrain to do the same.

Indeed, many Arab states – Qatar being the exception – have expressed interest in normalizing relations with the Assad regime.

Egypt was the first to do so in 2013 after Abdel Fattah el-Sissi overthrew Mohammad Morsi as Egypt's president.

Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Zayed, commonly known as MBZ, is currently making the final arrangements to rehabilitate Assad among his Arab peers, although not at the international level.

Arab countries seeking to reestablish diplomatic ties with Syria don’t insist that Assad initiate reforms or release political prisoners as a precondition for normalization.

They do, however, want to encourage Assad to distance himself from Iran.

They see normalization as the first step toward curtailing Iran’s influence in Syria, which would ultimately erode its dominance of Iraqi politics, choke Hezbollah, and convince Tehran to abandon its drive to dominate the region.

Assad, meanwhile, needs to secure a solid Arab political ally to advance his unbridled business interests.

The UAE, a stable and prosperous Arab state, fits the bill.

During his recent visit to the country, Assad landed in Dubai, the business capital of the UAE, and departed from Abu Dhabi, its political capital.

He explored with his hosts in both cities new horizons for cooperation in vital domains.

Assad’s UAE interlocutors said they wanted to invest in renewable energy and real estate development in Syria.

They were keen on not antagonizing Iran before the conflict ends and reconstruction funds are made available.

To justify the trip, MBZ said ending the conflict requires pragmatism and that, without a conclusion to the war, Iran will consolidate its hold on Syria, especially now that Russia is preoccupied in Ukraine.

As for Israel, many believe that both Israel and the Syrian regime want to normalize relations, but in reality neither country is interested in signing a formal peace treaty, though Israel remains committed to Assad’s political survival.

His father, who ruled Syria from 1971 until his death in 2000, refused to sign a peace treaty with Israel because resisting Israel was his only source of popular legitimacy.

But Israel also saw no reason to make peace with a country that didn’t have the military capability to challenge it on the battlefield.

For both countries, establishing formal relations is unimportant and should not prevent them from cooperating either directly or through the UAE.

Disdain for Iran

Iran, meanwhile, is worried about Syria’s reintegration in the Arab world and Assad’s intentions, especially after his visit to the UAE.

Even though Iran and its Shiite proxies – with the support of Russian airpower – helped prevent the collapse of the regime in Damascus, Assad dislikes Iran and loathes its religious ideology.

He’s stuck in an alliance started by his late father, who sided with Iran in 1980 in its war against his rival Baathist Party in Iraq.

In Syria, Iran is quietly trying to create a class of citizens loyal to it, similar to Hezbollah in Lebanon, and tailors its economic activities to the poor.

Tehran has been pressing Assad to grant Iranian businesses long-term contracts lasting up to 50 years to invest in electricity, roads, bridges and construction.

The two countries recently established a joint bank in preparation for post-war reconstruction and economic rehabilitation efforts.

They also agreed to develop several free trade areas in Syria to promote Iranian exports that currently constitute only 3 percent of Syrian imports – a small fraction compared to 30 percent of imports from Turkey.

Iran is trying to alter the foundations of its influence in post-war Syria, from a substantial military presence to economic dominance, despite Assad’s subtle resistance.

He regards Russia as the guarantor of his regime and of Alawite security, and is therefore willing to grant Moscow a significant stake in Syria’s recovery.

So far, Russia has made substantial investments in the phosphate and oil sectors, a petrochemicals plant in Homs, and the Tartus commercial port.

But Assad is unwilling to give Iran an equal share in the post-war economy, despite Iran receiving promises of cooperation and participating in business conferences that resulted in nothing more than pictures for the media.

In spite of the robust cultural ties between the two countries – thanks to Tehran’s sustained efforts over the past two decades to promote Iranian culture, religion, language, education and history in Syria – Alawites view Iran with disdain, believing that Tehran tried to proselytize them into its faith.

Economic ties between the two countries are also weak, deliberately blunted by Assad.

The Syrian leader has avoided making substantial economic commitments to Iran, signing financial deals with Iranian companies but never implementing them.

This arrangement is causing increased frustration in Tehran.

Since the 2011 uprising, Iran has spent around $30 billion to shore up the Syrian regime and wants to claim the economic spoils of peace.

Russia's Limits

MBZ believes that Moscow can play a critical role in stabilizing the Assad regime and in enabling Israel to degrade Iran’s assets in Syria.

It’s unclear to what extent Russia’s war in Ukraine will adversely impact Middle Eastern leaders’ perception of Moscow as a global power.

But in the long term, Russia’s deployment in Syria is not viable and will not make it a Mediterranean military power.

Russia’s foreign policy differs strikingly from the United States’ in that it lacks focus and depth, pursuing opportunities regardless of geographic location.

Russia’s post-Soviet foreign policy is defined by the Primakov Doctrine, charted in 1996, which aims to establish Russia as an independent center of power in foreign affairs to end U.S. global hegemony.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and President Vladimir Putin have moved to put the doctrine into action in Russia’s near abroad.

To aid them in this endeavor, Russian forces gained valuable experience in Syria.

Last year, Russian Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu told executives of helicopter manufacturer Rostvertol that, in Syria, Moscow was able to test and perfect its state-of-the-art Mi-35M attack helicopter, along with more than 320 other weapons.

Russian pilots gained training on targeting hospitals, schools, markets and factories, an experience that is proving helpful in the war in Ukraine.

Russian air power decimated anti-Assad forces, enabling the regime and Iranian proxies to prevail in the war after two years of inconclusive battle.

However, after its brutal use of indiscriminate attacks, it’s unlikely that Russia will be able to exploit Syria’s hydrocarbon assets.

It seems that Assad’s visit to the UAE – during an international crisis whose end is uncertain – was premature.

Russia’s conduct in Ukraine is reminiscent of its indiscriminate air campaign in Syria.

Its significant military difficulties will likely encourage Iran to contest Russia’s supremacy in Syria, either consolidating Tehran’s position or triggering a massive Israeli military action.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario