Keep your eyes on US housing

And will profitable tech follow unprofitable tech down?

Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu

Good morning.

Last week wrapped up with strong jobs data and more yield curve inversion.

If you’re worried about recession, ambivalent data probably isn’t helping.

The best place to watch for clues is the US housing market.

More on that below.

Also, tech, of both the profitable and unprofitable sort.

The soft landing and the housing market

Market consensus calls for the economy slowing through the end of next year, but not falling into a recession.

This makes sense, in a broad way.

The economy is roaring, as evidenced by the labour market.

It would be odd to bet on a recession, even a couple of years from now, when unemployment is running at 3.6 per cent.

At the same time, CPI inflation is almost 8 per cent, and showing no signs of subsiding.

The Fed is embarking on a tightening cycle and indulging in Volckerian rhetoric.

That sort of thing often ends in recession.

So we might state the consensus view as “everything is cool, unless inflation gets worse, in which case the Fed tightens us into a recession, which will not be cool”.

The distinguishing feature of the different views on offer across Wall Street is the probability that inflation does, in fact, get worse.

But everybody seems to have a 60/40 bet of some kind going, with most people placing the greater weight on avoiding recession.

Here for example is John Higgins, markets economist at Capital Economics:

The US stock market has often held up well in the early stages of a Fed tightening cycle, only keeling over once higher interest rates have shown signs of weighing on the economy and recession has loomed.

So, the ongoing strength of the labour market, evident in today’s employment report, suggests there may be life left in the equity rally.

That chimes with our own view, in which growth slows, without a recession, amid tighter Fed policy and even higher bond yields . . .

[But] we doubt that the US stock market, whose valuation remains rather high by some measures, would continue to make big strides if Treasury yields kept climbing in response to a further big increase in inflation that elicited a much bolder policy response from the Fed.

There are a few people out there who have the bet weighted to the downside.

Mitsubishi UFG’s US macro strategy team, for example, sees it as a 45/55 bet, leaning toward stagnation, stagflation or recession.

Here is their probability distribution for the next 18 months:

Goldilocks: Probability 20 per cent

Mid-cycle slowdown: Probability 25 per cent

Stagnation: Probability 5 per cent

Stagflation: Probability 20 per cent

Recession: Probability 30 per cent

How an even spread of probabilities like that is supposed to guide action I don’t know, but I sympathise with the analysts.

It does seem like we’re in a genuinely uncertain moment.

The last time we had inflation like this, over 40 years ago, the US economy was a completely different beast.

Nobody can really know what’s next.

Admitting that, as of now, even the medium-term future is unusually opaque, the question becomes: what indicators do we watch closely as we try to pierce the fog?

As we’ve noted before, housing is the obvious place to start, because it is a big, cyclical part of the economy that is particularly sensitive to rates.

Home prices also affect how rich people feel.

Since the start of the year, average 30-year mortgage rates have risen from 3.3 to 4.9 per cent.

That blindingly rapid increase is set to cool the housing market, according to the economics team at Redfin, a brokerage.

They saw the initial jump in rates as encouraging “get in while you can” purchases, but that phase of the cycle is over:

Mortgage rates are shooting up at the fastest pace in history, sending the typical monthly mortgage payment for a homebuyer up more than $500 since the beginning of this year. As rates quickly approach 5 per cent, we expect their impact on homebuyer demand to change from a motivator . . . to a deterrent

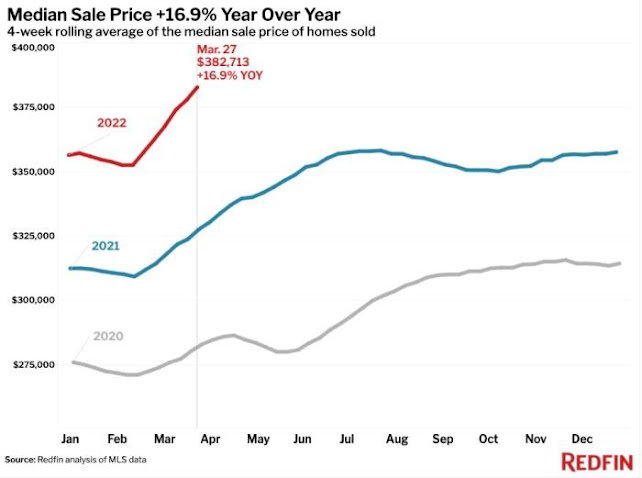

This has not shown up in home prices yet, according to aggregate data from brokers.

On the contrary:

Given historic tightness in the inventory of houses for sale, it makes sense that it would take some time for higher mortgage rates to show up in house prices.

So evidence of a housing slowdown is for now anecdotal, or nearly so.

The Mortgage Bankers Association’s weekly mortgage application survey showed applications down 10 per cent year-over-year for the week ending March 25, its second straight week of notable decline, but that series is quite volatile.

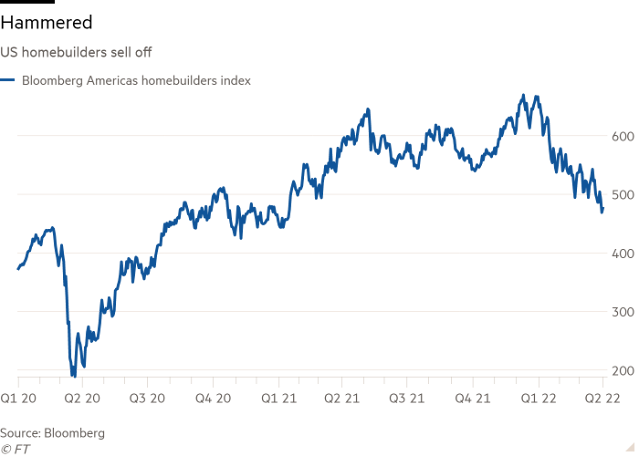

One market indicator has already rendered its verdict, however: the stock prices of homebuilders.

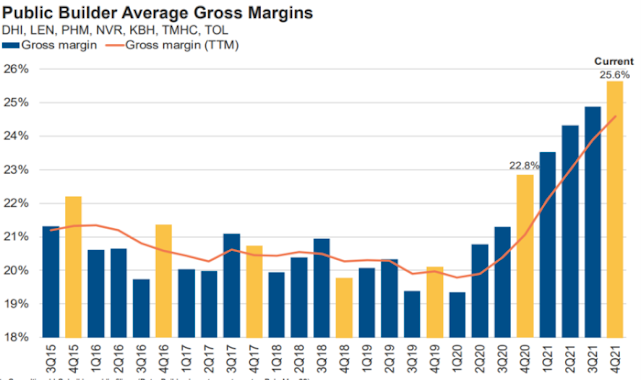

Right now, homebuilders are absolutely printing money, as this chart from John Burns real estate consulting shows:

But the stock market says builders are on borrowed time.

Their shares are down by almost 30 per cent this year, and are approaching their levels of before the pandemic boom:

Homebuilders’ price/earnings ratios are now hovering around 5.

As a rule, homebuilders sell off as rates rise, but this looks particularly brutal.

Profitless tech: omen or sideshow?

We’ve avoided the LOL@Ark pile-on in the past, but this weekend’s tweets from Ark Invest’s chief Cathie Wood are hard to resist:

Yesterday, the yield curve — as measured by the difference between the 10 year Treasury and 2 year Treasury yields — inverted, suggesting that the Fed is going to raise interest rates as growth and/or inflation surprise on the low side of expectations . . . which will be a mistake . . .

US consumer sentiment, as measured by the University of Michigan, is lower today than it was at the depths of the coronavirus crisis.

It has entered 2008-09 territory and is not far from the all time lows in the 80s when inflation and interest rates hit double digits.

The economy succumbed to recession in each of those periods.

Europe and China also are in difficult straits.

The Fed seems to be playing with fire.

This is confusing.

Wood interprets the partly inverted yield curve as signalling that the Fed will hike rates into a low-growth, low-inflation surprise — despite the central bank declining to raise rates until inflation was too hot to ignore, which is the cause of the terrible sentiment Wood mentions.

She seems to have things precisely backwards: the Fed would like nothing more than for inflation to come in cool and to hold off on rate increases.

It’s not raising rates for the heck of it.

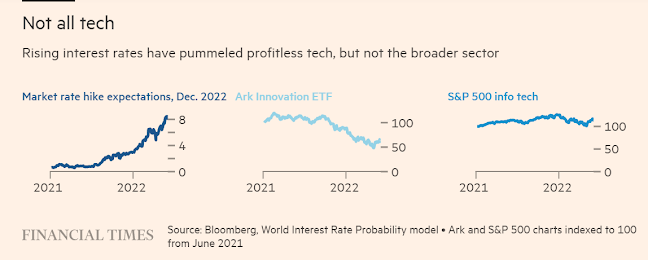

Perhaps not coincidentally, Wood’s growthy tech funds have been some of the biggest losers from rising rates.

Ark’s flagship innovation fund is down 57 per cent from its 2021 peak.

Many of the profitless tech stocks Ark fancies, including names like Teladoc and Peloton (which it dumped in late 2021), have reverted to pre-pandemic levels.

Meanwhile, broader tech indices are doing just fine:

Or are they?

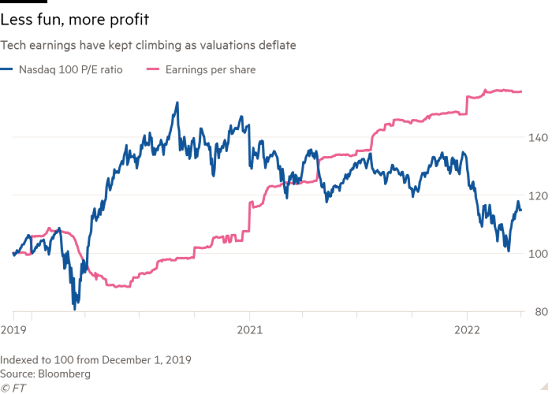

Tech indices have climbed somewhat slowly, even as earnings have come in strong quarter after quarter.

The result has been a marked drop in P/E ratios from pandemic highs.

The chart below is of the tech-heavy Nasdaq, but the trend holds for similar indices:

Some, like Bank of America’s Michael Hartnett, think that a regime change is coming that is bigger than just rates, and that it’s only a matter of time before regular tech catches up with profitless tech’s bruising crash. We ran this quote over in Adam Tooze’s Chartbook last week:

With the balkanization of the global financial system and internet, you don’t get the benefits of scale [tech thrives on].

Then liquidity dries up [as policy tightens and rates rise].

What kills a bull market in tech is saturation and regulation . . . for national security reasons regulation tightens, at the same time as rates go up, so valuations should go down, and the stuff that is most egregiously overvalued is damaged the most.

That happened already for unprofitable tech, and we have not seen it yet for profitable tech . . . tech is going to be the worst performing sector in the 2020s.

It’s still possible that tech is just adjusting from a strange low-rate pandemic world, and will stay strong as earnings keep impressing.

But we will be watching closely.

The question is which half of “profitless tech” matters more — the “profitless” or the “tech”. (Ethan Wu)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario