We must accept higher taxes to fund health and social care

The government’s response to immediate pressures on the system is inadequate and indefensible

Martin Wolf

An elderly patient is cared for in a Covid ward at the Victoria Hospital in Blackpool. The UK has a need for greater funding of services mainly used by the old © Lynsey Addario/Getty

“This government is committed to the delivery of world leading health and social care across the whole of the UK.”

That boast appears in the government’s recent Build Back Better: Our Plan for Health and Social Care.

It has, to its credit, recognised that health and social care were in crisis.

The question is whether its solutions are effective and fair.

The answer is: no.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies notes in its recent Green Budget that “between 2009−10 and 2019−20 UK government health spending grew at an average real-terms rate of 1.6 per cent per year — lower than any previous decade in NHS history.”

The waiting list for elective treatment had grown by 50 per cent from 2015.

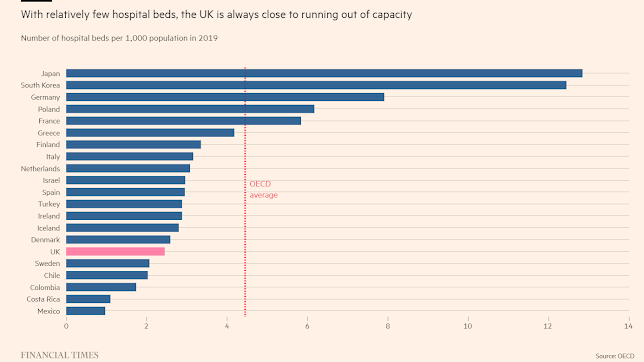

The NHS entered the pandemic with fewer doctors, hospital beds and CAT scanners per person than in most similar countries.

The system was creaking.

Then came the pandemic.

Rescue funding had become vital.

This has happened, with the new health and social care levy and the room for manoeuvre given by better than expected revenue forecasts.

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility the government has increased spending on health and social care by about £15bn a year.

Yet this will prove only a short-term fix. Given the ageing of the population, new treatments, growing demand and the inescapable rise in costs of labour-intensive services, the share of spending on health in national income will continue to rise.

The UK is in no way an outlier in terms of spending on health.

There is no reason to suppose it can avoid spending even more.

In addition, the government has decided to ameliorate the anomaly that care of the infirm and especially those suffering from dementia is not covered by the medical services, but falls on individuals, families and local authorities.

This has led to chronic underfunding and the unpopular need to sell houses in order to fund long-term care.

Is there an easy way to manage the pressure for a rising share of spending on health and social care?

A temporary one is austerity.

But in the end that blows up.

Feast and then famine is a ridiculous way to run an essential service.

Another is a hypothecated tax, such as the new levy.

But that is just window dressing.

Does anybody imagine that spending on these services will be slashed just because a particular tax raises less revenue than expected?

Another is to move towards an insurance basis for funding health.

But quite apart from the upheaval, compulsory insurance is just another tax.

The answer then is to accept that average taxes will rise slowly over time.

The question is who pays them.

Here the new levy is a disgrace — a politically predictable disgrace, but a disgrace all the same.

The country has a need for greater funding of services mainly used by the old.

So the government raises a levy of 1.25 per cent on earnings of employees and on wage costs of employers, creating a 2.5 per cent overall increase in the tax rate on earnings.

While taxable dividends are covered by the levy, neither rents nor pensions are.

The levy also falls more heavily on employees than on the self-employed.

Why should that be?

It is unjustifiable.

The health service is used by everybody.

The obvious and fair way was to raise the income taxes paid by all.

Consider, too, the new proposals on social care.

The main aim is to protect middle-class people from having to sell their homes to fund nursing home care and so dilute or lose their bequests.

It is possible to understand why this risk should be insured, but not that it should be funded by a levy on employees.

The obvious way to fund it would have been via taxes on gifts and bequests.

Worse still, the government has decided to save money on the proposal by massively penalising those with small wealth in favour of those with much more.

The Health Foundation notes that under the current system people can lose all but £14,250 of their assets.

For someone with £100,000 this represents 86 per cent of their wealth.

Under the 2014 Care Act, this would have been reduced to 43 per cent.

But under the government’s recent proposals the maximum loss would be £80,000, or 80 per cent of their assets, while those with £500,000 would lose only 17 per cent.

Why should the poor lose almost everything and the richer lose so little?

This really is an utter scandal.

The country has still not recognised the long-term need to accept rising taxation in order to deliver the services people will demand. There is no realistic alternative.

The government has however recognised the need to manage the immediate pressures.

The problem is that its solutions are dreadful.

They may work politically, but they are morally and intellectually indefensible.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario