Researchers on the Omicron Variant

"We Are Playing with Fire"

Scientists around the world are scrambling to find answers to critical questions about the new coronavirus variant, including whether vaccines are still effective against it. Initial data suggests that Omicron is spreading faster than Delta.

By Rafaela von Bredow, Marco Evers, Fritz Schaap und Veronika Hackenbroch

Omicron made itself known to the world on Nov. 4, a warm Thursday afternoon.

In Pretoria, South Africa, Alicia Vermeulen, a junior scientist at Lancet Laboratories, was going through a list of results from the day’s routine tests when she came across a strange discrepancy.

The PCR test, which reacts to three telltale sites in the coronavirus genome, struck only two of these sites in one sample.

It gave Vermeulen a moment of pause.

She told South Africa’s News24 that it made her curious.

She knew right away that something strange was going on.

She immediately informed her superiors, and Vermeulen says they decided to keep an eye on it.

The next day, another sample turned up with an odd result, and by the next week, they started piling up.

Vermeulen and her lab managers sounded the alarm.

The South African Network for Genomic Surveillance was informed, and by 3 p.m. on Tuesday of last week, the file made it to the desk of Tulio de Oliveira, a bioinformatician and geneticist who heads one of South Africa’s largest sequencing labs at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban.

"We got around 100 randomly selected samples from Gauteng from dozens of clinics and sequenced them in our laboratory," de Oliveira told DER SPIEGEL.

The World Health Organization was alerted, and the sequences were sent to "some of the top virus experts in the world," the researcher says.

The lab results arrived at 8 a.m. on a Thursday morning.

They all pointed to the same, very specific mutation.

Laboratory data showed that thousands of people were already being infected with the new virus every day.

"We had had just 200 to 300 cases a day nationwide in the first two weeks of November," de Oliveira says.

"And then this rapid spread – we were really very concerned."

Although he hopes the new variant will ultimately prove to be a "pussy cat," he says he fears it will be a "bad monster tiger."

That same day, Nov. 25, de Oliveira announced at a press conference that researchers had discovered a new variant of SARS-CoV-2.

A day later, WHO classified it as a "variant of concern” and christened it "Omicron," diplomatically and gently skipping over the letter "xi" in the Greek alphabet, a mutant name the Chinese might have resented.

Fear has been circulating ever since.

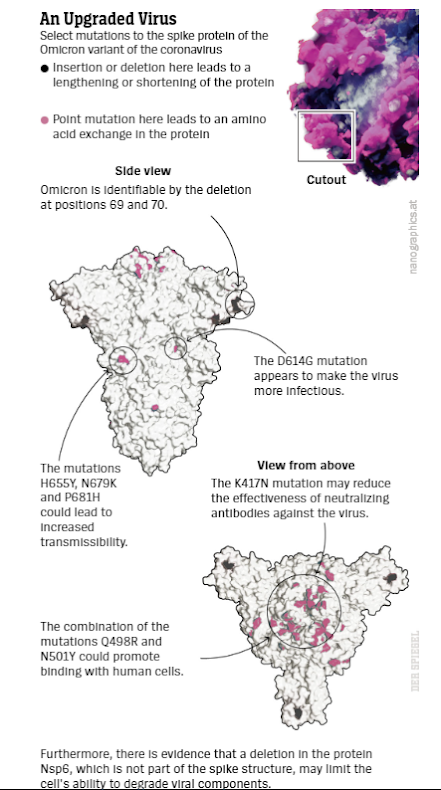

Never before has there been a SARS-CoV-2 virus with more potentially dangerous mutations, a good 50 in number, a whopping 32 of them in the viral region with which the pathogen binds to the cells of its host and invades them before multiplying millions of times.

Researchers around the world have been scrambling in recent days to find out as much as they can about the variant.

The most important question is whether the vaccines are still effective against it.

Is it helpful if a person has already recovered from an infection with a previous variant?

Is Omicron more transmissible than Delta?

Also, how sick does the mutant make people?

It will take some time before we have solid answers.

"It’s still very early," says Wolfgang Preiser, a German virologist at Stellenbosch University near Cape Town.

"We don’t have a culture of the virus yet."

Even with tricks, Omicron is difficult to "coax out of the cells," explains virologist Alex Sigal of the Africa Health Research Institute in Durban.

Preiser expects the first results of important tests "in two weeks."

So far, most of the clues have been found in Omicron’s genetic material. And many of the mutations are already familiar ones: Alpha and Delta already benefited from the same genetic changes.

It appears as though Omicron has raided the arsenals of its kin and grabbed a number of their most vicious weapons.

And it has forged new ones as well – some of the mutations have never been seen by researchers before.

Mutations can transform a virus in several ways: They can either make it more aggressive and more contagious, like Delta.

Or they help the pathogen to outsmart its host’s immune defenses – "escape mutations," as they are called because they escape the defenses the host puts up.

Omicron Is Everywhere

Omicron’s mutations could give it both superpowers at once: It could infect people who have recovered from the coronavirus or have been vaccinated against it, and it could be more contagious than other variants.

It is also unclear whether the new virus makes infected people sicker – or if it is possibly even milder.

No one knows how this abundance of mutations will play out "in real life," as Harvard epidemiologist Mary Bushman puts it.

"Unfortunately, the data we have doesn’t allow us to distinguish between transmissibility, immune escape or other factors."

What is known, though, is that Omicron has arrived on every continent except Antarctica, and it is rapidly spreading around the globe.

The variant has also been found in people who haven’t been to Africa.

In Germany, 12 Omicron infections have been confirmed so far. In regions of South Africa and Botswana, Omicron has already largely eliminated the previously dominant Delta variant, an indication that this pathogen may be capable of more than any coronavirus before it.

A combination of increased infectiousness and tricking the immune system would be particularly dangerous.

Over the summer, Mary Bushman simulated the kind of havoc a mutant like that could wreak.

The mathematician saw "devastating consequences" looming.

She warned that the double effect would be far greater than the sum of the two individual effects.

Now Bushman may have the chance to verify how well her models reflect reality.

On Monday, she began feeding the few things that we do know and assumptions about Omicron into her models.

"A key part of that will be simulating Omicron’s spread in countries with different levels of vaccination coverage,” she says.

"I’m hoping to have preliminary results in the next week."

There are three theories about the origins of Omicron currently circulating.

They are based on the finding that the mutant isn’t a direct descendant of Delta, Alpha or other variants of concern.

From its genetic makeup, it is clear that Omicron's origins go back as far as spring of 2020.

"It hung around somewhere for a long time," says South African infectious disease biologist Alex Sigal, "without being discovered."

One possibility is that the virus infected an animal at the time and mutated further before now making the jump back to humans.

Or it emerged in a country with an extremely reclusive population.

Prominent German virologist Sandra Ciesek of Frankfurt said in an interview with DER SPIEGEL that she believes the variant may have originated in "a region where virus genomes aren't sequenced as often, and it simply wasn't identified.”

That idea appears to be backed by the large number of mutations.

"Something like this doesn’t form within just a couple days, it takes time,” she says.

Viral Evolution

Alex Sigal has a different theory about Omicron’s evolution.

"The virus lived in a single person all this time," he suspects, "and kept evolving until it had enough critical mass or mutations to infect other people."

Then it broke out.

In a study published over the summer in the British Medical Journal, Sigal and Tulio de Oliveira observed just how spooky that viral evolution can be in a human host.

A 36-year-old woman carried the coronavirus for a full 216 days.

Her body had been unable to defeat it because her immune system was weakened by a poorly treated HIV infection.

The bodies of immunocompromised individuals can act as breeding grounds for mutants – not just HIV patients, but also organ recipients or other patients whose body’s defenses have been lowered by medication.

This phenomenon has been documented many times in studies.

"The immune system still fights back a little," Alex Sigal explains, "but not fiercely enough to get rid of the virus."

But it is fierce enough to put pressure on the virus: The host shows the intruder the weapons, but doesn’t shoot.

This allows the pathogen to learn more about the immune response and adapt.

If that continues for months or even a year and half, the virus can acquire useful mutations, equipping it to fight the tricks of the human immune defense.

Each time the researchers took samples from the HIV patient, the coronavirus had accumulated additional mutations.

Among them are those that can now also be found in Omicron.

Wolfgang Preiser, the German virologist in Cape Town, backs Sigal’s theory, citing a similar case.

He reports that until last week, a woman infected with HIV at the Stellenbosch University Hospital had also been infected with the coronavirus "at least since the beginning of this year – continuously."

Preiser says researchers have observed "that poorly treated or untreated HIV patients remain infected and also infectious for many months."

He says there are few documented cases, "but probably tens of thousands of patients with poorly treated HIV infections in South Africa with advanced immunodeficiency."

How dangerous can a mutant be that has developed inside an immune compromised human?

Sigal thinks it is possible that it also makes vaccinated people sick, but he, like most researchers interviewed for this article, believes that immunization will at least protect against severe cases of the disease.

He says there are few documented cases, "but probably tens of thousands of patients with poorly treated HIV infections in South Africa with advanced immunodeficiency."

The researcher also draws another comforting thought from his work.

"Maybe Omicron doesn't make you very sick," he says.

A virus that persists for months in a person with immunosuppression cannot be heavily pathogenic."

It doesn’t make sense from a viral perspective, either.

"You would die with your host," he says.

There has been a lot of debate about this since Angelique Coetzee, chair of the South African Medical Association, announced last weekend that there have primarily been mild cases from the variant in the country.

Experts say this could be due to the fact that not enough time has passed since Omicron began spreading on a larger scale.

It usually takes a couple of weeks for SARS-CoV-2 variants to affect people severely enough to require hospitalization.

In addition, the mutant is infecting a much younger population in South Africa than in Europe, and severe courses of the disease are rarer in younger people.

No matter how dangerous Omicron ultimately proves to be, "I think we will have to learn the Greek alphabet up to the end," he says.

The variants Pi, Rho, Sigma, Tau and Ypsilon will follow, and we have an awfully long way to go to Omega.

"The coming months and years will be rough," predicts Volker Thiel, a German virologist at the University of Bern.

In the rich countries, many had already thought "the worst of the pandemic was behind us,” says Jeremy Farrar, who heads the Wellcome Trust, one of the world’s largest foundations supporting medical research.

"The Omicron variant now reminds us all, that we remain closer to the start of the pandemic than the end."

He says humanity needs to prepare for a future that will be different for some time to come.

Life as it was before the coronavirus is unlikely to return for years for most people because the more infections, and thus virus carriers, there are, the more likely it is that dangerous new variants will spread.

And this doesn’t apply exclusively to immunocompromised people.

During the past 28 days, nearly 15 million people tested positive around the world, and the real figure is likely to be many times that number.

The viruses are winning the war right now.

Is Omicron a consequence of the unequal distribution of vaccines, which is especially affecting Africa, where fewer than 10 percent of the population is fully vaccinated in many countries?

And isn’t there a need for a global vaccination strategy to combat Omicron and similar variants?

That thought isn’t a new one.

The international community organized the COVAX initiative to make COVID vaccines available to the world, and it was a step in the right direction, says Maximilian Mayer, a policy researcher and expert on global technology policy at the University of Bonn in Germany.

But he criticizes the effort as being far too small.

Mayer is calling for a "new global vaccination infrastructure."

He says vaccine factories need to be set up on every continent and production needs to be ramped up quickly.

He also believes vaccine patents should be temporarily lifted.

"This is not only about the coronavirus, but also about all the other viruses that will threaten us in the future,” he says.

Mayer argues that the vaccination infrastructure would almost be cheap compared to the costs of the epidemics the world would face without that protection.

He suggests that NATO member states, in a one-off move, could divert 5 percent of their defense spending into vaccine production, an action that would also improve global security in the long term.

Farrar, from Wellcome Trust, sees the unwillingness to provide everyone with equal access to the vaccines, testing and treatment as a "lack of political leadership" that prolongs the pandemic for everyone.

"We are playing with fire,” he says.

"We are not yet in control of this pandemic, and a worse variant could arise at any time."

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario