Turkey’s Rate Debacle Is a Warning for Emerging-Markets Investors

President Erdogan’s experiments show why central banks in developing nations can’t just copy their Western peers

By Jon Sindreu

When central banks in the West behave chaotically, those in developing countries have even less room to mess around. Turkey doesn’t seem to have gotten the memo.

On Thursday, the Turkish lira fell 2% against the U.S. dollar after Turkey’s central bank lowered interest rates for a third time in a row.

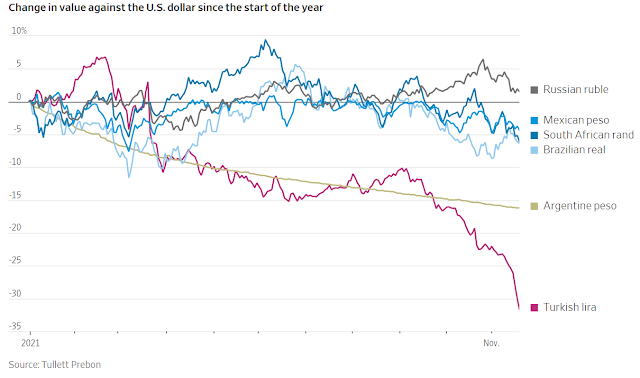

The lira has plummeted 30% since the start of the year, losing all the stability gained under the tenure of the previous central-bank governor, who was succeeded in March.

Although many on Wall Street expected emerging-markets stocks to be big beneficiaries of the pandemic recovery, they have returned a paltry 4% this year.

Emerging-markets currencies have been under severe pressure from Covid-19 variants, a surge in inflation and expectations of higher rates in rich nations.

Yet the lira is by far the worst performer, and it is mostly about monetary policy.

While Turkey is understandably wary of increasing borrowing costs as growth flounders, most developing economies have had to bite the bullet—as the South African Reserve Bank did Thursday.

By contrast, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan insists he will keep lowering them as he “writes the book on the economy.”

Some of the past decade’s monetary experiments, such as quantitative easing, have translated well to developing countries.

Often, though, borrowing from the rich-country playbook can be a costly mistake.

Of late, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have been inconsistent regarding whether they will aggressively raise rates.

Markets periodically have priced in that they will start doing so, but then have to stop or even reverse course.

Part of the confusion stems from how poorly textbook theories that linked interest rates to unemployment and inflation have fared. Since today’s inflation is mostly about pandemic-induced shortages, there is even more reason to believe rates can stay low as growth accelerates.

None of this applies to poorer nations: Their exchange rates are so volatile that currency depreciations can destroy living standards and fuel a self-sustaining inflationary surge, regardless of what started it.

It is essential to have a credible monetary policy that can raise rates to prevent hot foreign money from fleeing.

Capital controls can be useful, but they also need to be implemented coherently.

All of this gets even harder when the top central banks in rich nations are making U-turns.

Turkey illustrates the problem: A weak currency has helped exports grow at a faster clip than imports and thus swing the current-account balance to a surplus.

Yet inflation is so high—20%, compared with the current 15% interest rate—that big gains in competitiveness are no longer being achieved in real terms, data by the Bank for International Settlements suggests.

And while Turkish firms have mostly stopped borrowing in dollars, steep depreciations mean that the outstanding net foreign debt burden isn’t getting smaller. Inflation then fuels more depreciation, and so on.

Foreign-currency reserves could stop the spiral, and they appear to have been replenished.

It is a mirage, however, because most of those reserves represent borrowed money.

Without swaps and forward contracts, the country’s war chest is a negative $50 billion.

The first lesson for investors is that trying to call a bottom on the lira is probably futile.

The second is that even in other emerging nations, the current period of central-bank indecision makes for a perilous market.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario