The Labor Shortage Is Getting Worse. A Return to ‘Normal’ Looks Questionable.

By Lisa Beilfuss

Many economists expected hiring in September to pick up as millions of workers re-enter the workforce after pandemic lockdowns and child-care disruptions. Here, the morning commute in Chicago. / Scott Olson/Getty Images

Many economists expected hiring in September to pick up as millions of workers re-enter the workforce after pandemic lockdowns and child-care disruptions. Here, the morning commute in Chicago. / Scott Olson/Getty ImagesWhere are America’s workers?

Economists, Federal Reserve officials and employers alike had for months held out hope that millions of workers would re-enter the labor force in September, when enhanced federal unemployment benefits expired and in-person school resumed after a year of remote learning kept many parents from working.

The September jobs report finally dropped, and it showed anything but a rush back to work.

There is one good explanation that can’t be dismissed.

The fast-spreading Covid-19 Delta variant no doubt curtailed some return-to-work plans, especially in industries hit hardest by the pandemic.

That’s as jobs in public education declined a massive 144,000—what many analysts attribute to a seasonal adjustment.

And there are other reasons to look beyond the worst hiring since December.

Job growth in August was revised much higher while July payrolls also got a boost, meaning job growth in the three months through September averaged 550,000, notes PNC chief economist Gus Faucher.

At the same time, the unemployment rate tumbled to 4.8%, the lowest level since March 2020 as the pandemic was getting under way.

Those reasons to stay optimistic only go so far, however, to ameliorate another month of paltry hiring.

There is another way of reading through the headline weakness, and it’s far less positive: September’s employment report is an inflation signal more than it is a labor market signal.

“This is certainly an inflationary report,” says Citi economist Veronica Clark.

“Fed officials should look at this and be more worried about inflation,” she says, adding that the Delta effect explains only a small part of the worsening labor shortage.

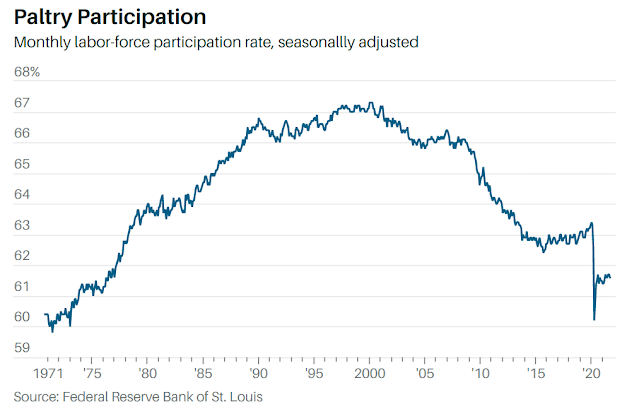

Consider that the drop in unemployment is in large part a function of a shrinking labor force, which declined a tenth of a percentage point last month.

As labor supply remains short, wages rose 0.6% from August, the fastest pace since April, when the comparison was against pandemic-depressed figures.

Sure, the September payroll survey was conducted in the thick of the Delta spike.

But it is time to ask whether economists, policy makers and investors are overattributing the labor shortage to temporary Covid-19 factors.

The labor force is still down about 4.9 million since the start of the pandemic, and it increasingly looks like many of the displaced may not return, says Michael Darda, chief economist at MKM Partners, meaning they are effectively out of the labor supply equation and shouldn’t be counted in measures of slack that have justified ongoing extraordinarily easy monetary policies.

For evidence, he points to the number of labor force dropouts who say they want a job.

Darda says that measure, if added to the unemployed population, tends to track the unemployment rate.

Early in the pandemic, the gauge was unusually high relative to the unemployment rate, but that is no longer the case.

The current reading of 8.2% is only 3.4 percentage points above the actual unemployment rate of 4.8% and close to the pre-Covid average of 3.3 percentage points, says Darda.

“In other words, the idea that there is a reserve army of the unemployed despite a 4.8% unemployment rate is belied by this data.

Moreover, the nature of the pandemic may have changed the natural rate of unemployment and thus changed the configuration of future wage and inflation rates relative to unemployment rates,” he says.

There are good reasons to believe many workers aren’t coming back.

In addition to lasting Covid concerns, economists and strategists point to early retirements and a reassessment of “work” by millions of Americans.

A record number of businesses have been launched since the pandemic started, and Luke Tilley and Tony Roth, chief economist and chief investment officer, respectively, at Wilmington Trust, note that a recent Harris Poll showed 55% of respondents said they know someone who has quit a job because “you only live once.”

The fast drop in unemployment is great until it’s not.

Darda says that if the average monthly decline observed this year continues, the unemployment rate would fall to 2.9% by mid-2022—roughly around when the Fed expects to fully taper its monthly bond-buying program.

And it would stand at 1.6% by the end of 2022, which is before many officials say they expect to start lifting interest rates.

The point is that current monetary policy and forecasts are built on the expectation that we return to a pre-Covid labor market that increasingly looks like it may no longer exist.

If that is the case, then where does that leave the Fed and investors?

As the Fed waits for millions to return to work before lifting interest rates, inflation continues to build.

“The reality is nominal demand is back to its pre-Covid trend growth path and likely to continue growing much faster than [capacity] as the pandemic recedes and the economy reopens into a nearly $4 trillion wall of money/spendable assets,” says Darda.

Citi’s Clark notes excess savings are now about 10% of gross domestic product, possibly giving some younger workers a couple more months of leisure before rejoining the workforce.

She isn’t counting out a delayed re-entry by many workers but says it looks increasingly elusive.

If millions of workers are gone for good, it’s a much different story than the one the Fed is telling.

For all officials’ talk of tools to deal with inflation, there really is just one: Interest rates will have to rise sooner and faster.

The longer inflation and the forces behind it are left to work themselves out, the higher the risk the problem is harder to correct.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario