China’s Economy Rests on Three Shaky Legs

There is little sign so far of a major shift to support growth, but that may reflect overconfidence on Beijing’s part

By Nathaniel Taplin

Coaxing buyers back into the property market may be tough without a more decisive resolution to the problems with Evergrande. The company’s headquarters in Shenzhen. / PHOTO: NOEL CELIS/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

Coaxing buyers back into the property market may be tough without a more decisive resolution to the problems with Evergrande. The company’s headquarters in Shenzhen. / PHOTO: NOEL CELIS/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGESChina’s economy has been taking it from all sides: power outages, the property debt fiasco, snarled shipping lanes and, a bit further back, a brief but damaging Delta variant outbreak.

Sharply weaker growth last quarter at 4.9% from a year earlier was expected.

And given how modest countercyclical support has been so far, next quarter will almost certainly be worse.

What happens in 2022 remains uncertain but appears to depend primarily on three things: how fast Beijing dials back its squeeze on the property sector, whether consumers finally perk up again, and whether exporters can hang on to recent market-share gains.

Power outages remain a drag, but efforts to restart shuttered coal mines and raise power prices will help significantly.

On property, there have been inklings recently of a more permissive stance—some large banks have been ordered to accelerate mortgage approvals, according to Bloomberg.

But credit growth was still tepid in September, and the sharp downtrends in property investment, sales and starts remain intact.

Since developers’ other financing channels have constricted so sharply, the key to turning things around is sales—but coaxing skittish buyers back into the market may be tough without a more decisive resolution to Evergrande’s woes.

Sales of residential floor space were down 16% from a year earlier in September.

The news on consumers and trade looks better. Chinese exports remain robust, and retail sales bounced back in September to 4.4% growth year-over-year, up from 2.5% in August.

The real risk for 2022 may therefore be that Beijing concludes that its strategy of doubling down on exports and high-tech industry, while mercilessly squeezing property and high-value service sectors like internet technology, is working well enough—and then finds itself overtaken by events.

One possible threat is an export reversal.

Chinese exporters, despite rising costs, remain very competitive.

But they have also benefited from the Delta wave that closed many other Asian factories and prolonged the shift in wealthy economies away from spending on services and toward goods.

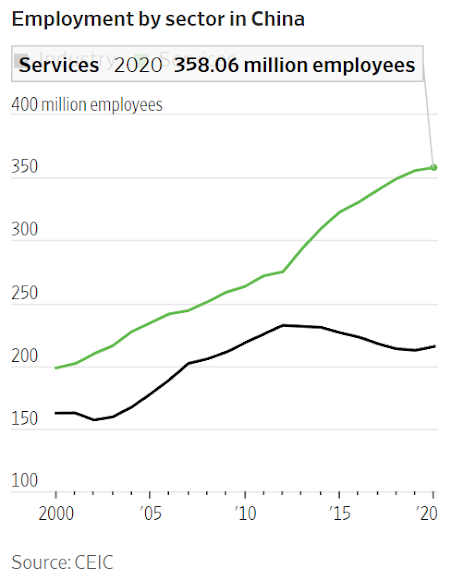

In 2020, net employment gains in Chinese industry outpaced those in services for the first time since 2012, a pattern that may very well have been repeated this year.

Some of that shift is destined to be transient, however, as wealthy economies finally reach vaccination thresholds high enough for service spending to really recover, and overseas competitors ramp back up manufacturing.

In theory consumers still have significant scope to increase spending: on a per capita basis, Chinese residents saved about 34% of their disposable income in the first nine months of 2021, up from an average of about 32% from 2017 to 2019.

But if the property market remains in the doldrums or other sources of jobs growth like exports fade, consumers may remain cautious, too.

So far Beijing has managed to avoid major turbulence from the property downturn, but it is early days yet.

If more significant policy easing doesn’t arrive soon, there is a serious risk that most of the major drivers of Chinese growth—property investment, consumption and exports—all find themselves pointing downward together by mid-2022.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario