What’s so great about private equity (part 1)

Robert Armstrong

On Monday I took note of the new head of Yale’s fabulously successful endowment, and his commitment to its huge allocation to private capital — more than a third of the endowment’s assets.

It has been (from what I can tell) a big source of Yale’s strong returns.

But I wonder where the extra return comes from.

Is it leverage?

Managerial skill?

Something else?

The literature on this topic is so vast I’m starting to regret having asked the question.

All I can do at this point is report on the first steps of what promises to be a long journey.

I’ll start with private equity, the biggest sub-category of private markets.

Where better to begin than with the man who designed Yale’s strategy.

Here is David Swensen, who ran the endowment until his untimely death earlier this year, in an 2017 interview, talking about PE.

The interviewer asked Swensen a question about leverage versus managerial skill as a source of PE returns:

I think the private equity . . . where you buy the company, you make the company better . . . and then you sell the company is a superior form of capitalism. I’m really concerned about what’s going on in our public markets.

I think short-termism is incredibly damaging.

There’s this focus on quarter-to-quarter earnings.

There’s this focus on whether you’re a penny short or a penny above the estimate . . .

If you compare and contrast that with the — let’s say the buyout world, where you’ve got hands-on operators that are going to improve the quality of the companies, there’s no pressure for quarter-to-quarter performance.

There’s no pressure to return cash at any cost.

There’s an opportunity, with a five to seven-year time horizon, to engage in intelligent capital investments that will improve the long-term prospects of the company.

A superior form of capitalism!

Intelligent capital investments!

Drinks on me!

What we have there is a theory of superior PE returns, from one of the smartest portfolio managers ever: less short-termism means better long-term returns.

Swensen being Swensen, he added a jab at the industry’s fees:

The only problem is that you have to pay 20 per cent of the profits.

Right?

And that’s the hurdle, right?

You have to [give] 20 per cent of the profits to the operator.

If there were a fair deal structure, you wouldn’t want to put anything into the public securities markets.

You’d want it all in private equity.

With Swensen’s endorsement in mind, I went to look for what the outperformance actually looks like.

What I was surprised to discover is that the outperformance of US PE firms, at least for the last decade, is small and getting smaller.

How to measure PE returns is a debate in itself.

There are lots of numbers out there.

But they don’t disagree that much.

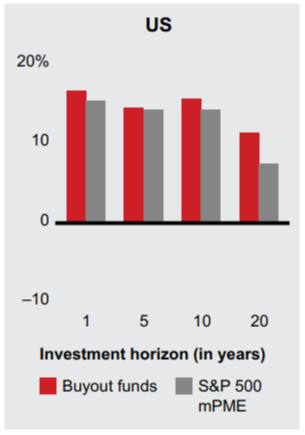

Here is a chart from Bain & Company’s 2021 Global Private Equity Report, comparing PE returns to S&P 500 returns, measured by internal rate of return:

PE had a good year last year.

But over five years it’s basically tied with the S&P, and at 10, it’s ahead by just a percentage point or two.

The good old days of the early 2000s are fading fast (relative returns in Asia and Europe are much better).

The Bain report from 2020 put the same data (one year less current) into a line graph, so you can really see the collapse of the return spread since the financial crisis:

Here is another look at the recent returns data, from Cliffwater Research, which looked at the returns of 66 state pension plans, with some $3tn in assets. Here is how PE did for those plans in the decade ending in 2020:

PE’s performance was about the same as that of US stocks over the past decade. All the data sets I have seen confirm this.

Now, if I thought, along with Swensen, that PE was a superior form of capitalism, I can think of three things I’d say in response to this lack of long-term outperformance:

1. US stocks have had a great decade. Keeping pace with them is impressive;

2. Of course the average PE fund doesn’t outperform stocks. You need to be with the best PE firms, with the most skill at improving companies’ operational performance, to see superior performance;

3. Higher returns are not the only virtue of PE. It’s the stability of those returns that sets this asset class apart.

Response number one fails. PE funds use a huge amount of leverage, and (until March last year) we had low market volatility and falling interest rates. If you can’t use your massive leverage to buy companies and beat the S&P under those conditions, you stink.

Number two does a little better. There may be individual PE funds that have a special sauce, just as there might be public equity funds that do (if anyone can say, in advance, which PE funds those are going to be, email me). But the question we are asking is about what generates returns for the asset class.

Number three is very interesting, and it connects to Swensen’s point. PE investments don’t get marked to market, so of course they are going to be less volatile. That does not mean that the value of the business is not going up and down all the time. It just means the owners have the privilege of not knowing what the day-to-day value is. Homeowners like myself have the same privilege with regards to the value of our houses. If we did not, we would go insane.

Likewise, those pension fund managers who are getting normal equity returns on their PE allocations may be getting paid in relaxation. The inclusion of PE brings the volatility of their reported results down.

Is this a good thing? I’m not sure. But people have strong opinions on the subject. Here is Dan Rasmussen of Verdad Capital, writing in 2018:

John Burr Williams, who invented modern finance theory, wished for a day when experts would set security prices. He believed that expert valuations would result in “fairer, steadier prices for the investing public”.

The PE industry would seem to have made Williams’s dreams come true. Experts, rather than markets, determine the prices of PE-owned companies . . .

The hurly-burly of the public markets is replaced by the considered judgment of an accounting firm that just so happens to be employed by the PE fund.

Rasmussen gives a powerful example. During the oil price crash in 2014-15, energy stock indices dropped by half, but energy private equity funds operating during that period were hardly marked down.

His conclusion is that the PE structure hides risk, and hiding risk is bad, because when risk is hidden, investors seeking returns push it higher and higher until something breaks:

To the extent that things do come out right in the end, reducing a few wiggles along the way really is not so problematic. But not seeing the wiggles can also encourage complacency, allowing valuations and leverage levels to climb and climb because the consequences of those decisions have not yet been felt. A lack of short-term accountability just means a delayed reckoning.

Is risk being pushed higher and higher? Well, here is the average leverage ratio equity deals, courtesy of PitchBook:

The trend in PE deal leverage is clearly up — from median debt of 4.5 times ebitda a decade ago to 7.5 times this year. Whether that leads to a crackup down the road, I have no idea.

Here is a rather speculative response to Rasmussen, though. The biggest PE firms can act to reduce actual volatility, not just perceived volatility. If you leveraged a bunch of your average small-cap public companies to 8 times ebitda, and a recession came along, a good portion of them would probably go bankrupt. But suppose it’s Blackstone or KKR who put all that leverage on. If their small caps are going bust, they can scare up some new money to keep them going; they know that recessions end. So the investors don’t lose all their money, as they would if they owned shares in a super-leveraged public company that went bust.

That response may not hold up to scrutiny, but it’s the best one I can think of right now.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario