Tiny Housing Bubbles

By John Mauldin

Recently I searched the Thoughts from the Frontline archives to see how often I used the word “bubble.”

It was more than I thought, and I wasn’t quoting Don Ho.

The bubbles

I talked about were anything but tiny. Most of them subsequently popped, too.

For most people, buying a home is the biggest single purchase they ever make.

It continues to represent the largest part of their net worth It is also the most leverage most people ever take on.

The risk of loss is very high

if you have little equity in the home and need to sell it.

Housing has other effects on the economy, too.

Booming home values contribute to a “wealth effect” that increases consumer confidence, making people spend more freely.

Some homeowners tap their equity to finance other purchases.

Some of it finds its way into the stock market.

The industries that

feed on all this—construction, building materials, mortgages, title companies,

real estate agents, etc.—are huge employers.

All of which says the housing sector is far more important than many realize.

They notice only when it falls apart.

Today home prices are being compared to the pre-2008 period, which was clearly a bubble that ended painfully for many.

Are we setting up for the same again?

I don’t think so.

Yes, the housing market is a bit overheated, but for reasons that make far more sense than the rationalizations of stock market bulls.

Some buyers are certainly overpaying and may regret it.

Nonetheless, I don’t foresee another 2008-style housing crash in the near future, nor anything like the subprime crisis.

There are altogether different fundamentals working here.

Manic Behavior

Let’s start with the obvious: The single-family home market is crazy hot right now. Many Americans want to relocate, for various reasons, and they outnumber the quantity of homes for sale.

No surprise, the market responds

with higher prices—sometimes far higher than seems justifiable.

On the other hand, basic economics says the “fair” price is the intersection of the amount the marginal buyer is willing to pay, and the amount the seller is willing to accept.

Whatever the rest of us think isn’t part of that equation.

It is somewhat murkier in housing because every product is one of a kind, based on its location, size, condition, and so on.

Houses aren’t like

shares of a company’s stock, all of which have identical characteristics and

thus identical value.

But in the current atmosphere, some houses are selling in a kind

of frenzy that resembles a crazy day in the stock market. Here’s one example,

via Business

Insider.

A California home received 122

offers in a single weekend amid a skyrocketing US real estate market.

The 1,400-square-foot home—located

in Citrus Heights, California, a suburb of Sacramento—was listed at $399,900.

It spans 1,400 square feet and has three bedrooms, two bathrooms, and a

swimming pool, according to a report from KTXL, the local Fox affiliate.

The house received 122 offers in

two days, including one above $500,000, and has since been sold for an

undisclosed amount—KTXL reports the selling price was "in the mid-$400,000

range."

If you’ve ever sold your home and waited weeks (I’ve had to wait months before) to get even one offer, the thought of 122 offers in two days is hard to process.

I would probably be kicking myself for not asking even more.

But this is happening all over the US.

The pandemic and its associated fear triggered a frenzy, at first with wealthy city-dwellers wanting to get away from the same crowds that attracted them to urban life.

Then, as companies let more of their staff work from home, people realized they could now live far from the office, in whatever location suited their desires.

So, we have a kind of giant card-shuffling

underway as millions reorganize their lives.

This will end, but for now it’s a flurry of activity.

Some people are making mistakes in their haste.

They buy houses requiring unanticipated repairs, or they move someplace that seemed nice then find it lacks what they wanted.

That is unfortunately what happens when you get in a hurry.

It’s unpleasant and maybe expensive for those affected, but the systemic effects probably aren’t great.

Damage to the person who overpaid is offset by extra

spending from the seller who got a windfall.

The bigger problem occurs when this activity sets up a price correction big enough to trigger a “negative wealth effect” that reduces consumer spending. Is that likely?

Dave Rosenberg thinks so.

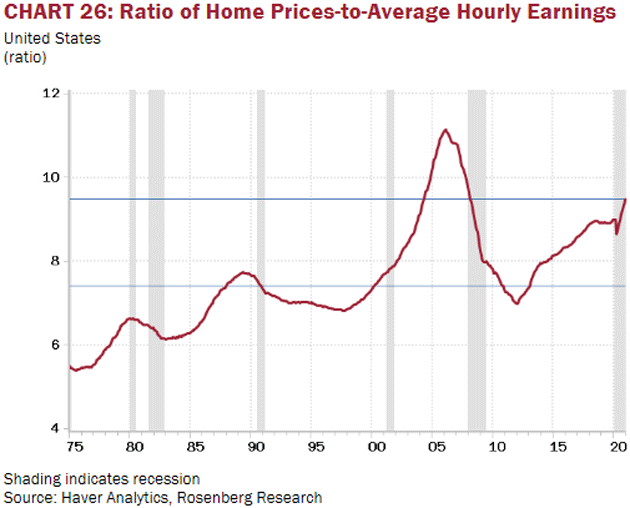

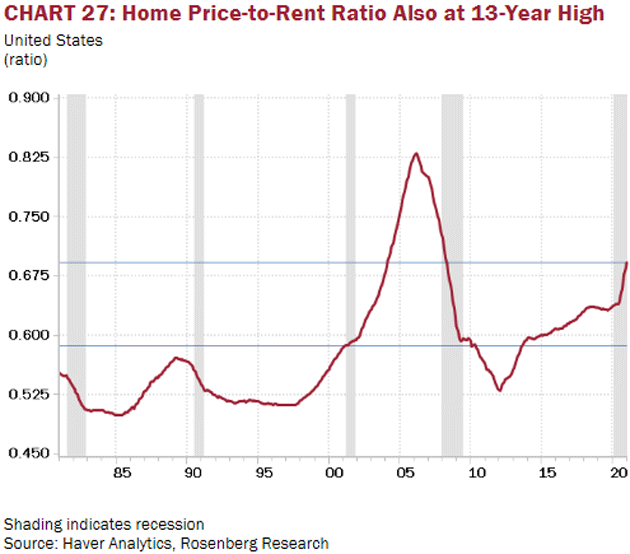

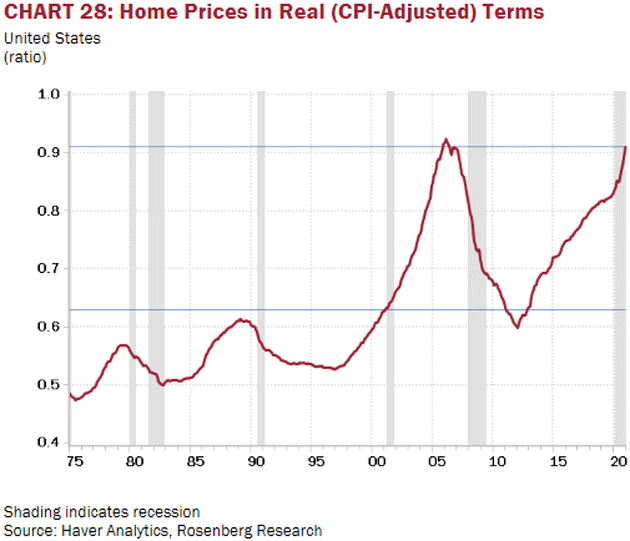

These charts are

from his March 31 morning letter.

Source: Haver Analytics & Rosenberg Research

Dave notes that all ratios are mean-reverting, and extremes like these tend not to continue.

He went on:

If the home price to CPI, to rent and to wage ratios ever did mean revert, which Bob Farrell’s Rule #1 says they will, we would be talking about a 20% decline in average home prices nationwide.

Maybe the catalyst will come from bond yields to mortgage rates, as was the case the last time around.

Remember—the home price erosion was happening as oil prices made their move above $100 per barrel and were on the way to a $150 per barrel peak.

You tell

me which of the two price movements exerted a more dramatic and lasting impact

on the economy, inflation, and the markets.

The US household sector is exposed to residential real estate to the tune of $32 trillion.

Tracing through the

negative wealth effect on spending would shave $400 billion, or close to 3%,

from consumption right there (and cut by half the stimulus right now being

directed to the personal sector—the thing is, any mean-reversion here on

residential real estate would have far more lasting effects than the short-term

fiscal relief, which has little more than a three-month shelf life).

Is that kind of price correction likely?

Maybe.

But there’s more to this story.

And while I agree that mean reversion is a real phenomenon, the data that we are going to examine suggests it may take quite some time for that mean reversion to come about, and may not be as dramatic as if it were all that happened in 2021/22.

Shrinking Inventory

When I write about specialized topics like real estate, I look for experts.

Fortunately, I know quite a few of them, and no one knows more about housing and mortgages than Barry and Dan Habib of MBS Highway. (Definitely check it out if you are in that industry.) I first met Barry around 2006, and he became part of my regular New York dinner crowd.

And he quickly became my go-to source on housing market questions.

He is a three-time winner of the Zillow/Pulsenomics Crystal Ball, awarded to the most accurate real estate trend forecaster, with three out of the last five years and the last two in a row.

Barry and Dan know this market

cold.

So, this week we had a phone call, which turned into a Zoom call so we could go through a dizzying array of charts.

The amount of data they track is staggering.

Even more impressive is the way they can distill it into

useful conclusions.

The bottom line is this: Looking at big-picture supply and demand factors, this housing bubble isn’t a bubble at all.

Yes, it’s overheated in some places, but housing trends move in slow-motion compared to stocks.

That

makes it critical to look at long-term data and ignore the monthly/quarterly

noise.

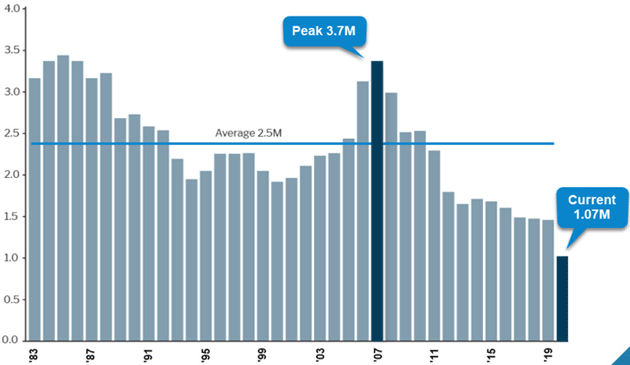

The first thing Barry explained is that housing “supply” isn’t the number of houses, but the number of houses for sale.

When that number is low relative to the number of prospective

buyers, prices rise.

You might think the US, being a dynamic if slow-growing economy the last decade, would have plenty of homes available.

Not so. Inventory has

actually been dropping for years.

Source: MBS Highway

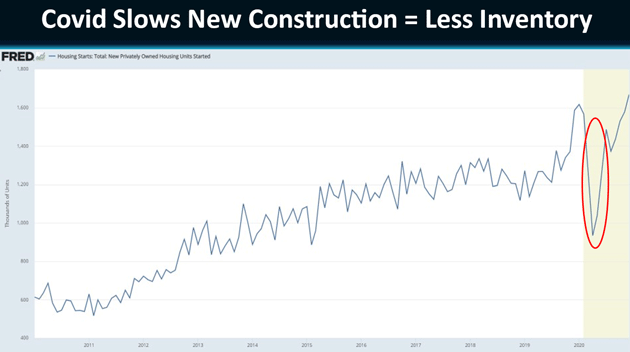

The single-family home for sale inventory peaked in 2007 and has fallen sharply since then, despite a growing population and economy.

Other things being equal, that alone would probably push prices much higher.

But all else wasn’t equal.

In early 2020 the world went upside down as the pandemic struck and much of the economy came to a near standstill.

In many places, that

included home construction.

Source: MBS Highway

This wasn’t just because shutdown orders made contractors stop work. Even in places where construction continued, material and labor shortages slowed progress.

The industry, which was already operating at a slower pace than in the past, basically lost about six months’ worth of production in 2020.

Higher existing home listings simply couldn’t replace that lost inventory.

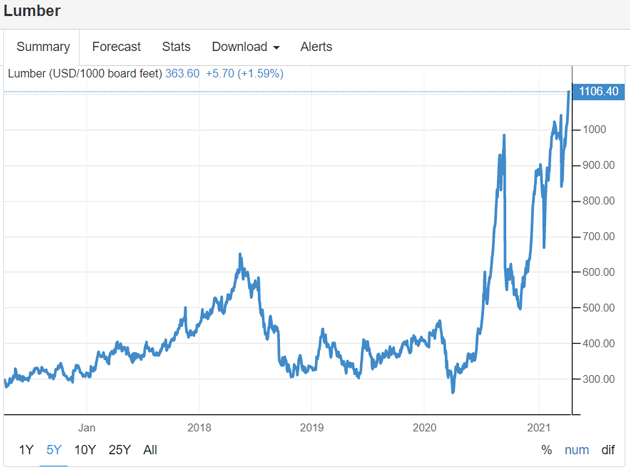

Material shortages were a factor, too, particular lumber. Back when I was younger and actually did work around the home, I remember buying plywood sheets for under $10.

It was still in that range as recently as 2018.

Last Saturday a friend was telling me about expanding his garage in New Orleans.

He is paying $87.50 for a 4 x 8 sheet of 5/8 inch plywood.

Ouch!

He

says it has now become the Garage Mahal.

Lumber prices have tripled from just a few years ago, if you can get it.

This all pushes construction costs higher, which further reduces

supply.

Source: Trading

Economics

So, the supply part of the equation was already tilted and the pandemic made it more so.

That’s why those ratios in Dave Rosenberg’s

charts above were rising so steadily in recent years. Prices should rise if supply

contracts, as long as demand remains at least steady.

But demand hasn’t been steady.

It is booming.

And it’s not just the pandemic.

Millennial Demand

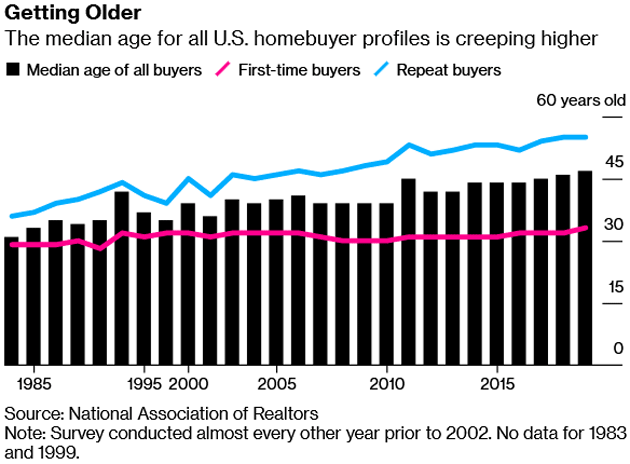

The key factor in housing demand is household formation.

Single people tend to live in apartments or rental homes.

They turn into homebuyers when they think about

having children, because they need more space and stability.

The age at which this happens has been remarkably steady around 33.

See the pink line in this chart from Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg

As Barry and Dan Habib point out, this means the number of 33-year-old Americans is crucial to housing demand, particularly at the less-expensive starter home end of the market.

More people of that age mean more homebuyers, and vice versa.

Of course, they have a chart to prove it.

Source: MBS Highway

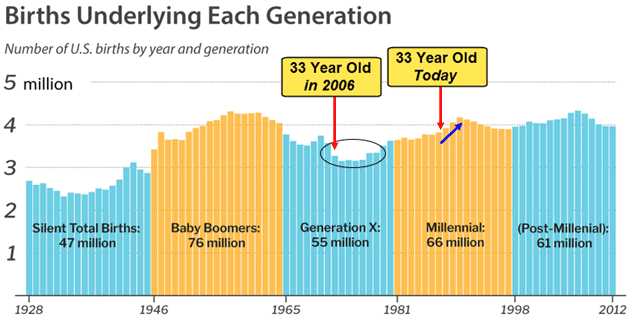

In other words, to gauge housing demand in any given year, look at birth rates 33 years earlier.

As the chart shows, the number of births fell quite a bit for several years beginning in 1973.

That meant fewer 33-year-old first-time homebuyers in 2006 and several years afterward.

It is not

coincidence the housing market ran into trouble about that time, though other

factors (like easy credit for people who wanted to flip houses) contributed as

well.

Today we have a different situation.

Those who are 33 now were born in 1987 and 1988.

At that point, births had been rising since the 1970s low and would accelerate further for a few more years.

That’s why the last few years saw heavy demand from first-time buyers, and why it should continue a while longer.

If you look at the graph you can see there’s another three or four

years of rising demographics, then a fairly slow decline.

Now add to this the retiring Baby Boomers who also want smaller homes as they enter downsizing mode.

As I wrote earlier, many people are looking to move to different locations as they are able to work from home much of the time.

We have sharply rising demand combined with sharply lower supply.

Of course, home prices have been rising.

They can hardly do otherwise.

But can the Millennials afford houses without higher wages?

Barry had a point there, too.

It’s really simple math.

Say home prices rise 10% and wages rise only 2%.

Houses are now less affordable, right?

Not exactly.

The key

is that your house payment isn’t your entire income.

Say you are considering a home purchase and the mortgage payment will be $1,000.

Your monthly income is $5,000.

That’s 20% of your income, which is

fairly typical.

If the home price is 10% higher and mortgage rates stay the same, the payment would go up to $1,100.

If your wages rise 2%, you would be making $5,100 a month.

Your income rose enough to pay for the higher-priced home.

Houses can stay affordable even if wages rise more slowly than home prices.

Not

indefinitely so, but for a while.

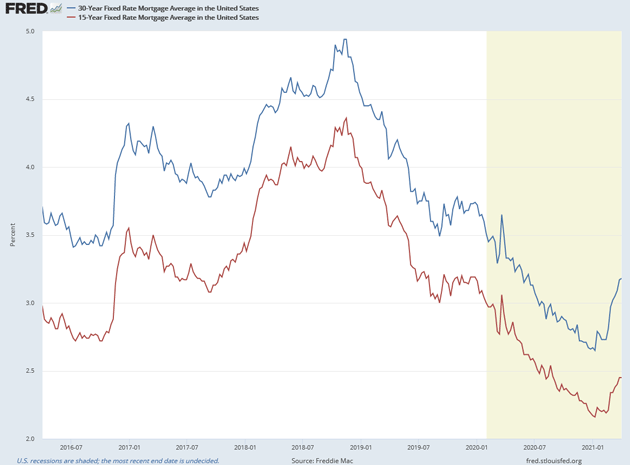

Now, we may

have a problem if mortgage rates keep rising, as they have recently.

Source: FRED

This is a potential problem for housing.

But it depends on Treasury yields, which I feel relatively confident that the Federal Reserve will not allow to rise much more.

What exactly they will do is anyone’s guess.

Some kind of yield curve control is a good bet as the federal debt spirals higher.

It will likely come in the form of more quantitative easing and an Operation Twist situation where they start buying longer-dated bonds.

They have little choice.

Intended or not, the policies that bail out our government should also serve to cap mortgage rates at historically low levels.

That’s another

bullish factor for home prices.

All that to say, housing may look like a bubble, but it’s only a tiny one. Our real problems are elsewhere.

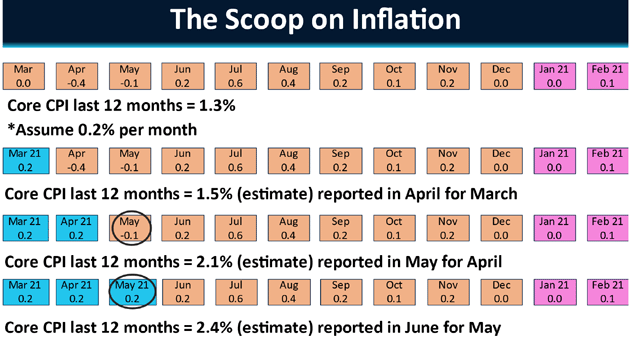

Some Thoughts on Inflation

In the middle of our conversation on housing, Barry, Dan, and I began to talk about the effects of inflation on mortgage rates.

I have noted before that the comparisons from one year ago beginning in March/April will make “headline inflation” appear to be soaring in the next few months.

That is because we had very low inflation this time last year, and prices are rising on many items across the board.

Barry agreed and showed me his own estimated

inflation chart.

Source: MBS Highway

Note that annual core inflation was just 1.3% a few months ago.

Inflation is roughly rising 0.2% a month, which is a reasonable base assumption.

If that is the case, we should see 1.5% inflation in March (reported in April).

But it will quickly rise to 2.1% and then 2.4% in April

and May, at that relatively benign 0.2% assumption.

I have smart and talented friends who believe the base assumption should be higher for the next six months.

I would not be surprised to see a 3% inflation number.

Jerome Powell and other Federal Reserve officials will tell us the number is transitory, and I would generally agree.

As we go back to normal, as supply chains actually get fixed, I expect the inflation numbers to go down.

Further, one year from now the comparisons will be from a much higher

base so it is likely that inflation will once again be below 2%.

For whatever reason, and I think it’s a silly reason, the Federal Reserve wants to keep rates low until we get back to 3.5% unemployment.

That is a number we have only seen twice in the past 60 years, once during the Vietnam War when we had half a million soldiers out of the workforce and again at the end of 2019.

Try as I might, I cannot see the linkage between financial repression with low rates and the unemployment rate again reaching an all-time low.

I would much rather have stable pricing and some actual coupon return on

my bond investments.

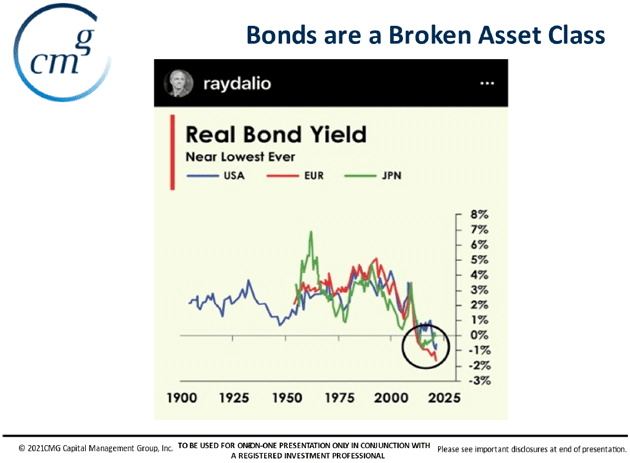

The standard 60/40 (stocks to bonds) portfolio is broken because bonds are broken.

Look at this chart from Ray Dalio courtesy of my friend Steve Blumenthal of CMG.

We literally have negative real rates in the bond markets and many institutional bond funds.

The bond part of the 60/40 strategy was supposed to reduce volatility and provide income.

When rates are rising it’s actually costing you money.

If you own a 10-year Treasury fund, you are down about 6% this year.

At a 1.7% yield, it will take the over three years just to get back to breakeven and that’s assuming that yields don’t rise even more.

Bonds are not providing either the income nor the volatility hedge.

Traditional

passive 60/40 investing is dead.

There are places you can find income in the private markets, but those don’t show up in ETFs or mutual funds.

There are reasonably good funds with trading strategies that produce bond-like characteristics.

Again, not the

traditional choice for most investment advisors.

Source: Steve Blumenthal

The Federal Reserve is forcing investors to move out the risk curve to generate income from their portfolios that they spent decades accumulating, hoping for enough to live on.

For Boomers and people looking to retire in the next 10 years, this is an absolutely insane policy.

But that is a topic for another letter and for the upcoming SIC.

I Can’t Wait to Get on the Road Again

Mauldin Economics readers have already signaled major interest in signing up for the SIC 2021, which again is all-virtual this year, for your safety and convenience.

I cannot tell you how delighted I am to see this level

of enthusiasm.

The SIC 2021 is less than a month away now (May 5–14), and we’ll reveal the full list of our blue-ribbon faculty next week.

We’re almost done confirming speakers, and I think you will be very, very pleased.

This is easily the finest lineup we’ve ever had.

If you haven’t yet, you can watch my welcome video with more details here.

This is also where you can pre-order your own SIC 2021 Pass at a substantial discount.

Trust me.

You are not going to want to miss this event.

Interesting factoid on Barry Habib: Aside from being a mortgage and real estate whiz, he’s an accomplished Broadway and film producer.

You may have enjoyed his Rock of Ages.

My sources are both brilliant and versatile.

Speaking of show business, Willie Nelson’s classic song, “On the Road Again” has been running through my mind the past few weeks.

While I might not make music with my friends, I do have wonderful times and miss it.

Some of my business partners are coming to Puerto Rico for a planning session at the beginning of May, then the SIC.

It looks like I will be in Palm Beach near the end of May, and I hope to get to New York City soon after and then Maine in August.

Other places and friends are calling my name as well.

For what it’s

worth, I had almost no reaction to my two vaccine shots except a sore arm.

And with that, I will hit the send button, and wish you a great week.

Stay safe and stay in touch by following me on Twitter.

Your looking forward to seeing old and new friends over dinner

analyst,

|

|

John

Mauldin |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario