The Enigma of Dubai

In Dubai's path to modernization, appearances can be deceiving.

By: Hilal Khashan

First-time visitors to Dubai get the impression that they about to enter to an austere Islamic city with strict codes of conduct.

They are warned against things like public displays of affection, using profane language and eating in public during Ramadan.

It doesn’t take long to realize, however, that these taboos are merely a veneer – in reality, people can do whatever they like so long as they don’t get caught.

Like in most traditional Arab societies, in Dubai, shame is the primary tool for enforcing compliance with social norms.

Thus, in more ways than one, Dubai is a paradox.

It presents itself as a unique, modern and rapidly developing economy.

Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, who ruled the emirate from 1958 until his death in 1990, introduced liberal economic policies.

But he also laid the groundwork for a maximum state security policy to maintain law and order and prevent the emergence of opposition groups, namely Islamist movements.

The paradox of Dubai is also apparent in the city’s long-standing problem with prostitution.

Sheikh Rashid was an innovator, but he was also a realist.

He knew he could not eliminate prostitution and instead grew to tolerate it.

Over time, the problem has become more complex and widespread, especially as the emirate began a comprehensive development process after the oil boom of the mid-1970s.

The sheikh’s vision fell short; he failed to foresee the untoward aspects of modernization that the emirate is all too familiar with today.

His successors did not encourage prostitution, human trafficking and shady business dealings, though neither did they stamp them out.

These illicit trades have become major facilitators of Dubai’s modernization and enigmatic rise.

Demography

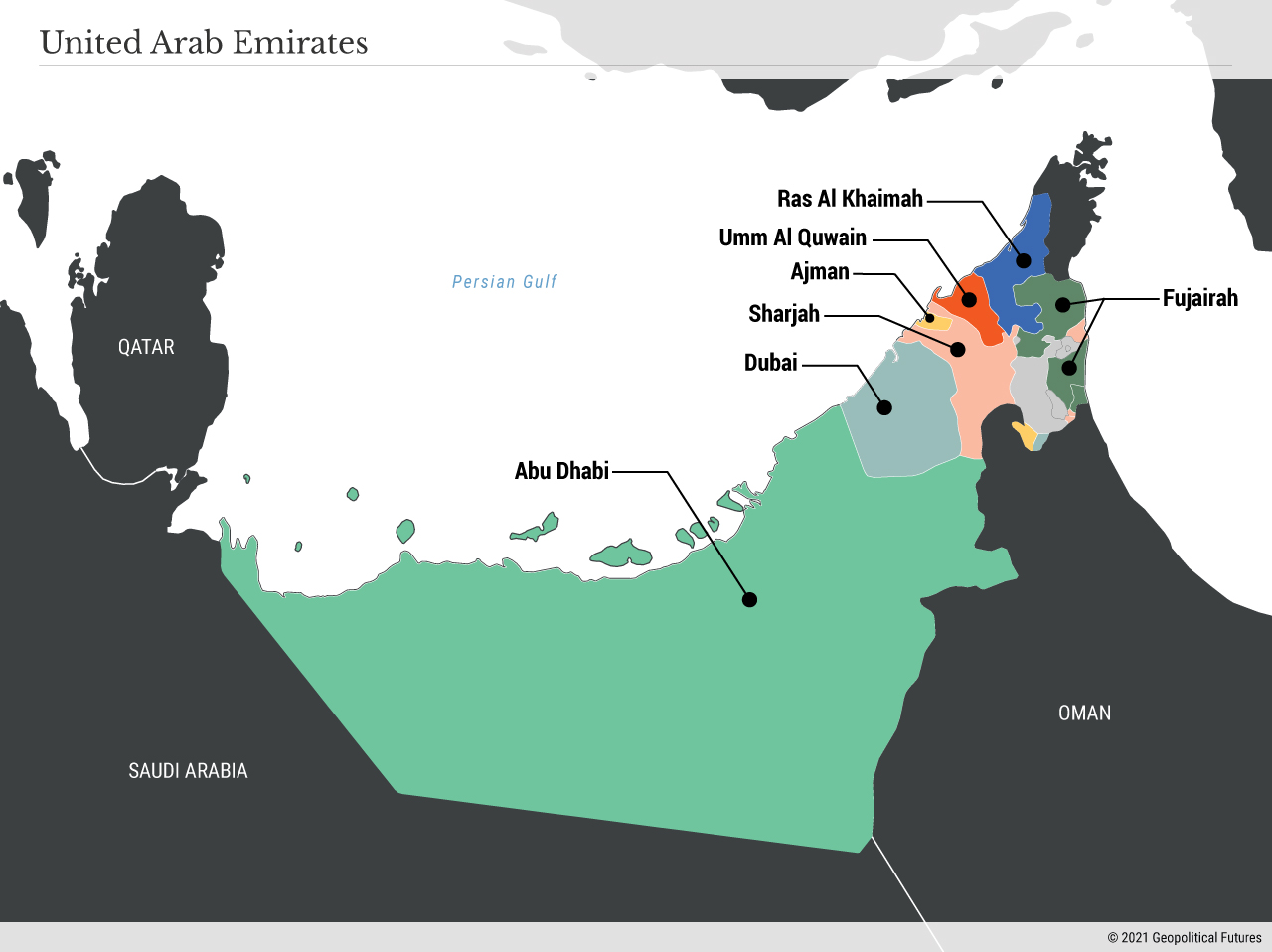

The Emirate of Dubai – one of seven emirates that comprise the United Arab Emirates – has a population of 3.3 million residents, only 12 percent (nearly 400,000) of whom are citizens, according to government figures.

Though there are no official statistics on the ethnicity of its citizens, there is a sizable ethnic Iranian minority.

Of the entire population, South Asians constitute around 60 percent, Iranian expatriates about 15 percent, and highly paid Westerners about five percent.

The rest are mostly Palestinians, Egyptians and Lebanese.

The nominal per capita income in Dubai is roughly $31,000, though this figure is a poor reflection of the economic position of most who live there.

Hundreds of thousands of Asian laborers receive an average monthly salary of about $150, while per capita income for locals is much higher than the nominal average.

The large presence of workers, mostly laborers, from the Indian subcontinent is a result of Dubai’s declaration as a British protectorate in 1892.

The British administered Dubai from the Persian Gulf Residency (headquartered in the Iranian city of Bushehr), which was subordinate to British India.

They allowed Indians to run Dubai’s civil service, commerce and banking.

Years later, Indian laborers flocked to Dubai after the discovery of oil in 1960.

Dubai was also a center of trade with Iran since the early 19th century, and many wealthy Iranians established permanent residence there.

Iranian investments in Dubai currently top $200 billion.

Economic Pillars

Dubai’s economy has three main pillars: Port Jebel Ali, tourism and air transport.

Opened in 1979, Port Jebel Ali is the ninth-largest port in the world and incorporates a vast manufacturing complex producing goods ranging from aluminum to a wide array of food and other consumer products.

It is Dubai’s top revenue generator, providing $53 billion annually, or about 60 percent of gross domestic product.

The port is also a key part of the UAE’s efforts to become a maritime power.

The UAE wants to protect the primacy of its main port from potential competitors in the Middle East and the Horn of Africa – which requires guaranteeing access to sea lanes leading to Port Jebel Ali, including the Strait of Hormuz, Bab el-Mandeb and the Suez Canal.

Thus, the UAE built military bases in Eritrea’s Assab port and Somaliland’s Berbera port. It also joined the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen’s civil war in 2015 to help secure its Arabian Sea coast, Socotra Island and the strategically located Aden port.

The UAE also supported Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi’s coup against Mohammed Morsi after Qatar promised to establish an industrial zone in the Suez Canal area – which Abu Dhabi viewed as a direct threat to Port Jebel Ali.

Another major source of revenue is tourism.

More than 16 million people visited Dubai in 2018. Most of Dubai’s tourism-related revenue, however, comes from prostitution, money laundering, smuggling and human trafficking.

Economic dividends from these activities are invested in real estate, construction and tourist infrastructure. Although Dubai has little tolerance for freedom of expression, relentlessly persecuting political activists and human rights advocates, it allows prostitution to go on unabated.

With more than 30,000 foreign prostitutes, Dubai has been dubbed the “Sodom-sur-Mer” – or Sodom by the sea.

A few years ago, a Saudi cleric also referred to Dubai as “sin city” before the government pressured him to rescind his statement.

Dubai has a well-developed infrastructure that sustains the prostitution industry, which is supported by tourists, expats and locals alike.

Unlike elsewhere in the Gulf, Dubai is known to quickly issue tourist visas, which are used by human trafficking businesses to recruit young women.

Upon arrival, they are given work permits in fake occupations and coerced into becoming sex workers.

Dubai is an international center for money laundering, which has contributed to its construction boom and infrastructure expansion.

There is no evidence that the government actually solicits money launderers; what is certain, however, is that it does not have a strict anti-money laundering policy comparable to most other countries, especially in the West – an omission that invites corruption and shady business activities.

Transparency International has accused the UAE of turning a blind eye to illegal business transactions, saying that it is “incredibly vulnerable to money laundering.”

Dubai is also a regional center for the illicit antiquities trade. International smugglers in Dubai have purchased artifacts stolen by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, which have ended up on display in Western museums.

Dubai’s economy is also dependent on the international narcotics trade. Close to $4 billion worth of heroin from Afghanistan is smuggled into Dubai annually.

According to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the eldest daughter of former Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos recently smuggled millions of dollars belonging to the diamond- and oil-rich country into Dubai, where she now claims residence.

The Human Toll

In 2016, the government in Dubai created a "ministry of happiness," a move that raised eyebrows given the extent of the human rights abuses there.

Indeed, the government has not made a sincere effort to deal with the prostitution issue. Indentured servitude is widespread.

And laborers, many of whom must give their entire first year’s salary to their employment agent, work under dismal conditions seven days a week and live in filthy accommodations. (At least two Indian laborers commit suicide each week, and there are likely many more suicide attempts that go unreported.)

Prostitution has been particularly resilient in Dubai and has had a significant human toll.

In 1936, Sheikh Saeed bin Maktoum tried to tackle it by coercing prostitutes to either get married or leave the emirate.

His successor, Sheikh Rashid, ordered that all prostitutes be deported, but this created a liquidity problem as they withdrew their savings from banks, forcing him to rethink his decision.

In 2019, the National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking dealt with just 23 cases of human trafficking, provided humanitarian support for 41 victims, and prosecuted 67 traffickers, all of them foreign.

The former head of Dubai’s police department acknowledged that prostitution and alcohol were a national affliction.

In 2006 and 2015, the UAE introduced laws aimed at conveying to Western countries that the UAE was keen on combatting human trafficking.

But its efforts rang hollow.

In reality, Dubai lacks the will to genuinely address the problem.

An Uncertain Future

Despite its glamour and appeal to foreigners, Dubai is a superficial city constituted by empty high-rise buildings with no distinct national, religious or cultural character.

It’s facing stiff competition from Gulf Cooperation Council countries that want to diversify their economies as oil prices fall. (Saudi Arabia’s Neom project is a prime case in point.)

COVID-19 has taken a heavy toll on Dubai’s economy and led to, among other things, the postponement of Expo 2020.

Its tourism and air travel industries have also been hit hard.

In 2019, they contributed some $35 billion to the emirate’s economy, or 40 percent of its GDP.

Dubai’s foreign debt exceeds $160 billion, or more than 150 percent of its GDP, and it’s unclear whether oil-rich Abu Dhabi will bail it out as it did in 2008 with a $20 billion loan.

Indeed, its soaring skyscrapers may no longer be able to obscure its unsustainable economic path.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario