The Limits of Syrian Kurdish Self-Determination

In Syria, the Kurdish question isn’t only about statehood.

By Hilal Khashan

The creation of the Kurdish Regional Government in northern Iraq in 1992 had a tremendous impact on Kurds throughout the Middle East. In Syria, the Kurdish minority saw it as an example of what could be achieved in their own country, especially after the military clampdown following the 2004 Qamishli riots, which began after a soccer match between Kurdish and Arab teams turned violent.

The Syrian uprising in 2011 and the withdrawal of government forces in the northeast gave Kurds hope that their time had finally arrived. But the subsequent turn of events demonstrated that achieving the same status that Kurds enjoy in Iraq is unattainable in Syria.

Stalled Project

In March 2016, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party, or PYD, established the autonomous region of Rojava, literally meaning west Kurdistan, in northern Syria. The new entity included Afrin and Kobani, cities along the Turkish border, and Jazira, a region east of the Euphrates River. Before the year’s end, the PYD renamed Rojava the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria.

It had a demographically diverse population that included Kurds, Arabs, Syriacs, Assyrians, Turkmen and Armenians. As an offshoot of the Kurdish Workers’ Party, or PKK, which advocated Kurdish statehood, the PYD seemed keen on presenting itself as a moderate and multiethnic political project that encompassed more than one-fourth of Syria’s territory.

But there were concerns, due at least in part to the PYD’s utopian slogans, that the federation was a stepping stone toward building a Kurdish state.

The federation’s military establishment is the multiethnic Syrian Defense Forces whose backbone is the PYD’s military wing, the People’s Protection Units, or YPG, and the Kurdish Asayish police force.

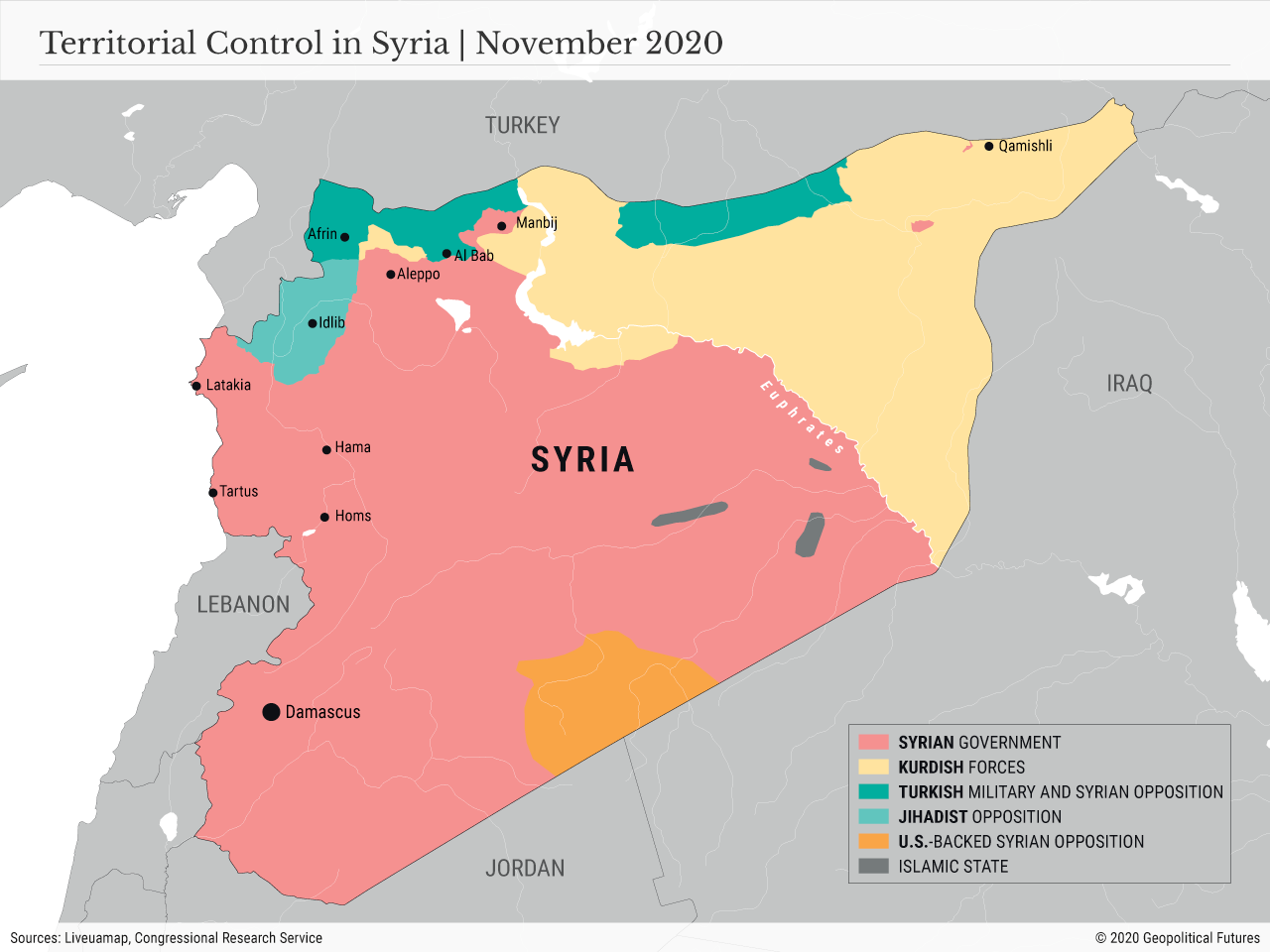

Following the Islamic State’s rout by the U.S.-backed YPG in 2016, Turkey launched three decisive military operations in northern Syria. They resulted in the Kurds’ loss of Afrin, a strategic border town for pro-Turkey Syrian rebels, and their pathway to the Mediterranean.

Just after U.S. President Donald Trump ordered the withdrawal of U.S. troops from northern Syria in October 2019, Turkey launched another assault, Operation Peace Spring, which led to additional territorial losses for the YPG and Turkey’s seizure of a 115-kilometer stretch of land between Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ayn.

The Kurds felt betrayed by the U.S. as well as by Russia, which had told them that it would not oppose their advance to the sea.

For the Kurds, the loss of their self-declared autonomous region’s geographic contiguity to the Turks and Manbij and Kobani to Syrian government forces was painful. They know that Damascus is hostile to their cause but believe it’s possible to reach a negotiated settlement with Damascus, unlike Ankara.

Indeed, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan made it abundantly clear, after the YPG removed IS from Kobani in 2015, that he would not tolerate a Kurdish regional government in Syria similar to the KRG in Iraq. Thus, despite Turkey’s strong ties to the KRG, Syrian Kurds view Turkey as the biggest adversary of the Kurdish people.

Victims of Geopolitics

Kurds throughout the Middle East have repeatedly suffered at the hands of other parties that have either overtly expressed opposition to their cause or claimed to be allies then turned their backs on the Kurds’ plight.

In the early 20th century, a spate of Kurdish uprisings threatened to destabilize Iraq and the newly formed Turkish republic. These outbursts of violence alarmed Turkey, Iran and Iraq, which, along with Afghanistan, signed the 1937 Treaty of Saadabad, a non-aggression pact that emphasized their commitment to preventing the Kurds from destabilizing the new regional order – that is, preventing them from establishing a state in the Zagros Mountains.

The Soviet Union supported Iranian Kurds in declaring the Republic of Mahabad in 1946 but soon after pulled out of northeastern Iran and failed to respond when the Iranian army crushed the republic and hanged its leaders.

Iran, for its part, has consistently encouraged Iraqi Kurds to rebel against Baghdad, though its connection to the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan in Iraq has been one reason for the party’s decline.

The West has repeatedly encouraged Kurdish nationalists to rebel against the state and then left them to face defeat. In 1880, the British let Kurdish nationalist leader Sheikh Ubeydullah’s revolt collapse after the Persian Qajars and Ottomans closed in on his tribal forces.

The Kurdish National Council, an umbrella movement in Syria that owes its formation in 2011 in Erbil to the KDP, repeatedly warned the PYD against trusting the U.S. and Russia, believing they would abandon it after IS was defeated.

Kurdish Identity

In Syria, the Kurdish question is unlikely to be answered by the formation of a federation in itself. Indeed, a long-term solution requires a negotiated national pact that recognizes their separate ethnic identity – an issue Syrian leaders failed to address when the country gained independence in 1943.

Urban Kurds in Syria have deep roots in the country and were well-integrated into society until the surge of Arab nationalism in the mid-1950s.

Ibrahim Hananu, a Kurd from Aleppo, emerged as a staunch defender of Syrian independence during the French mandate and was recognized as a national symbol. Khalid Bakdash, a Kurd from Damascus, led the Syrian Communist Party from 1936 until his death in 1995. Syria also had three presidents of Kurdish origin between 1949 and 1954: Husni al-Zaim, Fawzi Selou and Adib Shishakly.

But the emergence of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser as a charismatic pan-Arab leader galvanized many Syrians into demanding a merger with Egypt under his leadership. Kurds opposed the union, and in 1957, the newly formed Kurdish Democratic Party in Syria demanded recognition of Kurdish national identity.

After the formation of the United Arab Republic between Egypt and Syria in 1958, Nasser outlawed the party. The UAR dissolved in 1961, but that didn’t allay Kurdish apprehension about Arab nationalism.

The new leaders in Damascus adopted the Syrian Arab Republic as the country’s official name, and the following year, the government held an emergency census in the predominantly Kurdish Hasakah governorate that revoked the citizenship of 120,000 Kurds in Syria, claiming that they entered the country illegally from Iraq and Turkey.

Kurdish rural areas in Syria belong to Upper Mesopotamia, originally part of northwestern Iraq and southeastern Turkey. Following the signing of the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, the Anglo-French architects of the new regional order included them in Syria. Their inhabitants identify more with their compatriots in Turkey and Iraq than with those in Syria.

The 1963 coup in Damascus that ushered in Baathist rule exacerbated Syrian Kurds’ dilemma, especially after the discovery that same year of oil in the country’s northeast.

The new Syrian rulers dispatched troops to assist the Iraqi army in crushing the Kurdish rebellion in northern Iraq and prevent its spread into the Jazira region. In 1980, former Syrian President Hafez Assad decided to establish a 375-kilometer security belt along Syria’s borders with Iraq and Turkey in Jazira.

He used the agrarian reform law to displace 140,000 Kurds from the border area and resettle Arab tribespeople in their place.

Looking Ahead

Mainstream Kurdish movements in Iraq and Syria, such as the KDP and KNC, have come to terms with their limitations, realizing that they have to work with the national government to agree on a modus vivendi.

Turkey remains a major obstacle to Syrian Kurds’ establishment of a federalist system, but resolution of the Kurdish question in Syria hinges also on the establishment of a new political arrangement that recognizes the country’s sectarian and ethnic cleavages and redefines the meaning of citizenship and national identification.

Syrian Kurds want to be recognized as citizens but also want to have their cultural and linguistic origins acknowledged. The only lesson learned from a bloody and protracted conflict like Syria’s is that those who survive it construct a better system that avoids the pitfalls of the past. Syrians are still struggling to get there

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario