Not Quite a Lebanese-Israeli Entente

The two countries are participating in talks – though without actually talking to each other.

By: Caroline D. Rose

On Oct. 14, a delegation from the Lebanese government travelled by helicopter to the town of Ras Naqoura, just north of the Lebanese-Israeli border, and entered a room at the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon headquarters, where Israeli officials were waiting to discuss a decadeslong maritime dispute between the two countries. It was a remarkable event – the first time Israel and Lebanon have met for face-to-face talks on a civilian matter since 1990. But because they have no official diplomatic relations, their representatives spoke to each other only through U.S. and U.N. mediators in a terse exchange that lasted no longer than an hour.

At first glance, the timing of the meeting may seem peculiar. After all, Lebanon is in the middle of an economic crisis, while clashes between Hezbollah and Israel continue along the Lebanese and Syrian borders. Deep-held imperatives brought Israel and Lebanon to the negotiating table, but peace was not their primary goal. Rather, Israel sees a window of opportunity – while Beirut is weak and leaderless – to pressure Iran in Lebanon and score points with potential regional allies.

For Lebanon, the talks are financially motivated. With soaring debt (over 170 percent of gross domestic product), a spiraling currency and a dismal credit rating, it’s in desperate need of cash. If it manages to redraw maritime boundaries in its favor, it could tap into the Mediterranean’s rich natural gas deposits and attract foreign investment.

Origins of the Dispute

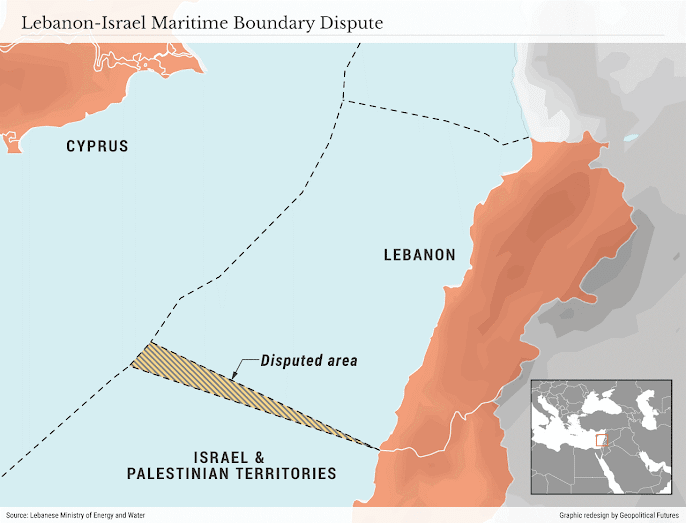

The two countries have long sparred over their borders. In 2000, the U.N.-administered “blue line” was established to define the line of withdrawal for Israeli forces in southern Lebanon, which has prevented large-scale cross-border incursions ever since, though occasional clashes have taken place between the Israel Defense Forces, the Lebanese army and Iran-backed militias. That arrangement, however, didn’t settle the spat over their maritime boundaries – a dispute that was aggravated by a series of natural gas discoveries off the coast of Israel, Cyprus and Egypt in the 2010s.

The discoveries introduced the possibility that Lebanon could tap into substantial natural gas reserves that potentially equaled those of its Mediterranean neighbors. After signing a delimitation agreement with Cyprus in 2007, Lebanon submitted its claim to an exclusive economic zone to the U.N., but it was undermined nearly a year later by an Israel-Cyprus deal that demarcated EEZs that overlapped with Lebanon’s own.

In 2011, the U.S. sent Ambassador Frederic C. Hoff to mediate the dispute. He established the “Hoff Line” that would have given Lebanon 550 square kilometers (210 square miles) of the 860 square kilometers Lebanon considered its territorial waters, but the talks soon fizzled out.

In 2018, Lebanon signed drilling contracts for two blocks – Block 8 and 9 – with energy giants Novatek, ENI and Total. But the dispute over maritime boundaries – and the companies’ concerns about angering Israel – have stalled exploration operations that were scheduled to be completed by May 2021.

Israel’s Other Objectives in Lebanon

For Israel, the Lebanese talks fit in to its recent thawing of tensions with other Middle Eastern nations. After signing normalization deals with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, it’s hopeful that other countries will also come to the table.

Though technically still at war with Lebanon, it sees public talks with Beirut as a way of building trust among other countries in the region, such as Oman, Sudan and Morocco, and neighbors with which it also has border disputes, such as Jordan.

But it also has broader objectives within Lebanon. Following the Beirut explosion in August and Prime Minister Hassan Diab’s resignation (he remains in his post until another leader can form a government), the Lebanese government is in a precarious position. By holding negotiations at this time, Israel is trying to take advantage of the power vacuum to reshape the power dynamics in the country – especially with regard to Iran-backed Hezbollah, one of the most powerful forces in Lebanese politics.

Israel and the U.S laid the groundwork for discussions with a series of punitive measures against Hezbollah. In September, the U.S. sanctioned two former Lebanese government officials, a Hezbollah Executive Council official, and two Lebanese companies accused of transferring funds and material to Hezbollah leaders. Just days later, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State David Schenker said Lebanon and Israel were “getting closer” to a framework for talks.

Publicly, of course, Hezbollah and its Shiite ally, the Amal Movement, criticized the negotiations, threatening to obstruct future talks and pressuring the government to change the composition of the Lebanese delegation hours before they were scheduled to take place. But privately, Hezbollah’s leadership had little choice but to agree to negotiations.

Its position was already weakening, with waning credibility, new sanctions and a teetering Lebanese government, not to mention dwindling funding from Iran (which was facing U.S sanctions of its own), increasing pressure from the pro-democracy, and overstretched resources following conflicts on the Israel border and the civil war in Syria.

The talks with Israel could add to its problems, making Hezbollah look “soft” on Israel, forcing it to make concessions and denying it justification for initiating future large-scale clashes.

But Hezbollah still wields considerable influence in Lebanon’s crippled government – enough to force President Michel Aoun to tighten the parameters of the talks by dropping civilian experts from the delegation and issuing statements that the negotiations were strictly about protecting Lebanon’s sovereignty.

Prime Minister Hassan Diab also expressed concerns about the delegation – saying it was selected without his approval and therefore violated the constitution – broadening the criticism across party lines and raising the risk that they could break down in the future.

Even if that happens, Lebanon and Israel have already signaled a pivot in their national strategies. Lebanon and Hezbollah have softened their stance on Israel, and Israel has extended an olive branch – though with the hope of further hurting Hezbollah’s credibility.

The two countries may not be speaking to each other directly, but it is notable that they sat at the table for talks in the first place.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario