How Egypt Lost Its Leadership of the Arab World

The country has gone a long way since its rise as a champion of Arab nationalism.

By: Hilal Khashan

For centuries, Egypt had positioned itself as a leader of the Arab world. Even before the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s second president and a major proponent of pan-Arabism, Egyptian leaders sought to unite Arabs from across the Middle East and North Africa.

But in recent years, the country has lost its place as the champion of Arab nationalism as it grows increasingly inwardly focused.

Egypt’s Rise

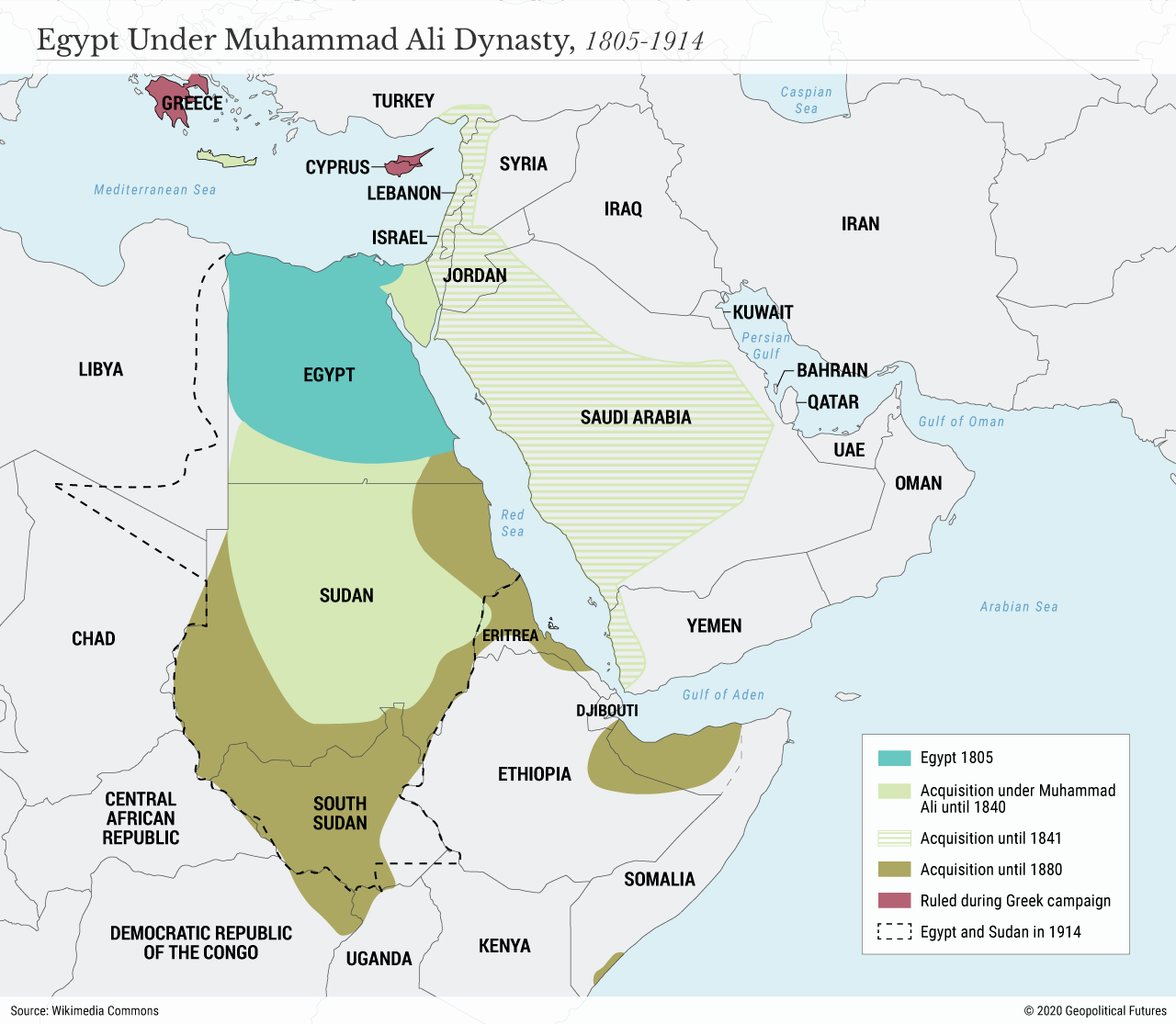

Egypt’s rise as the leader of the Arab world began in the early 19th century with an army officer and Ottoman governor named Muhammad Ali. After the British forced Napoleon out of Egypt in 1801, the Ottoman Empire sent Muhammad Ali, who was a military commander in the Balkans, to Egypt to rein in the Mamluks, who had dominated Egypt a few centuries prior.

Four years later, he declared himself viceroy of Egypt and ordered his son, Ibrahim Pasha, to create a dynasty for him. Not being ethnically Arab themselves, they believed that the Arab language would define the boundaries of their new state.

Ibrahim defeated the Ottoman army in 1832 in the Battle of Homs, in central Syria, and again in 1839 in the Battle of Nizip, in modern-day southeastern Turkey. However, the intervention of European powers halted his advance.

In the 1840 Convention of London, they convinced him to abandon his territorial ambitions while recognizing his father’s dynastic rule over Egypt – which lasted until a military coup in 1952 overthrew Ibrahim’s grandson, King Farouk, who rose to the throne in 1937.

Farouk entertained the idea of leading the Arabs, especially after the establishment of the Cairo-based Arab League in 1945. But his main rivals, Jordanian King Abdullah I and Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Said, also wanted to create an Arab state that would include Syria, Jordan and Iraq.

He realized that the endeavor would not succeed unless he could achieve a military victory against Israel. The opportunity came on May 14, 1948, when David Ben-Gurion announced the creation of the state of Israel and, later that same day, Farouk launched an assault on the newly formed state, against his army commanders’ advice.

But defeat in the first Arab-Israeli war tarnished Farouk’s image and, in addition to rampant state corruption and domestic unrest, set the stage for his ouster in the 1952 coup organized by the Free Officers Movement.

The coup ushered in Egypt’s first president, Mohammad Naguib, who was himself deposed just two years later by another leader of the Free Officers Movement, Gamal Abdel Nasser, who then declared himself premier.

Nasser understood that championing Arab nationalism and assuming a tough stand against Israel were key parts in Egypt’s modernization. He supported the national liberation movements in Asia and Africa and joined the Non-Alignment Movement as a founding member in 1961.

He initially embraced building relations with the U.S. through his dealings with CIA officer Kermit Roosevelt Jr., who saw pan-Arabism as a benign alternative to communism, which preoccupied President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration.

However, Nasser’s unpredictability and fiery anti-Western discourse concerned Washington. The U.S. denied his requests for arms, essentially to appease Britain, which saw Nasser as a threat. Nasser also declined to join the U.S.-backed, anti-Soviet Middle East Defense Organization, a military alliance formed in 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey and the United Kingdom as the Baghdad Pact.

The U.S. ultimately failed to temper Nasser’s worldview, during a tumultuous time in the Cold War. Frustrated by his decision to sign an arms deal with Czechoslovakia in 1955, the U.S. withdrew its financing of the Aswan Dam project. The damage to U.S.-Egyptian relations seemed irreparable.

Eisenhower’s opposition to the 1956 invasion of Egypt by Israel, France and the U.K. – ostensibly because Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal – had little impact on Nasser, who then sought to capitalize on his political gains, despite his military losses. He became the uncontested champion of Arab nationalism and, in 1958, created the United Arab Republic, a political union between Egypt and Syria.

The union crumbled, however, following a military coup in Damascus in 1961. After initially sending in paratroopers to suppress the rebellion, Nasser decided to call off the operation. His reluctance to use force to defeat the coup weakened his pan-Arab credentials.

To make up for his failure to salvage the union with Syria, he decided to deploy troops to Yemen to stabilize its new republican regime after the 1962 coup. Nasser’s venture into Yemen proved disastrous for Egypt on all accounts.

The five-year war drained Egypt’s meager financial resources, stalled its economic development, strained its relations with the U.S. and divided Arabs.

Nasser’s brief interlude of cooperation with President John F. Kennedy’s administration gave way to hostility and suspicion when Lyndon B. Johnson became president in 1963. Egypt’s dependence on U.S. wheat supplies, which in 1962 amounted to more than half its consumption, did not prevent Nasser from taking issue with Johnson’s foreign policy.

He viewed the US. Senate’s decision to withhold aid to anti-American states as directed against him – even though it wasn’t. He also viewed Johnson’s offer in 1967 to give Egypt a reduced wheat aid package worth $55 million as hostile.

Undeterred by his setbacks in Syria and Yemen, Nasser persuaded Libya’s King Idris Sanusi against renewing the U.S. Wheelus air base contract, condemned what he called the U.S.’ pseudo colonial Congo policy, and supported the Vietcong in the Vietnam War – moves that the Johnson administration saw as a bridge too far.

To add insult to injury, in 1964, rioters burned down the Kennedy Library in Cairo, and a few days later, Egyptian forces shot down a plane owned by a Texan businessman and personal friend of Johnson.

Decline of Egypt’s Leadership

The rise of the Fatah Movement and its raids in Israel beginning in January 1965 further threatened Nasser’s image as a pan-Arab leader. In public, he committed himself to returning refugees to Palestine. In reality, however, he opposed going to war against Israel because he knew he would lose.

On the 25th anniversary of the Battle of El Alamein, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery visited Egypt a few days before the Six-Day War and told senior Egyptian officers that they stood no chance in a war against Israel.

After the Soviets provided Nasser with false intelligence indicating Israel was massing troops on the Syrian border, Nasser ignored warnings from his own senior officer that the reports were false and sent troops to the Israeli border anyway.

When a senior officer reminded the chief of staff of the Egyptian Armed Forces that the military was not ready for war, he replied that the deployment was merely a demonstration of force.

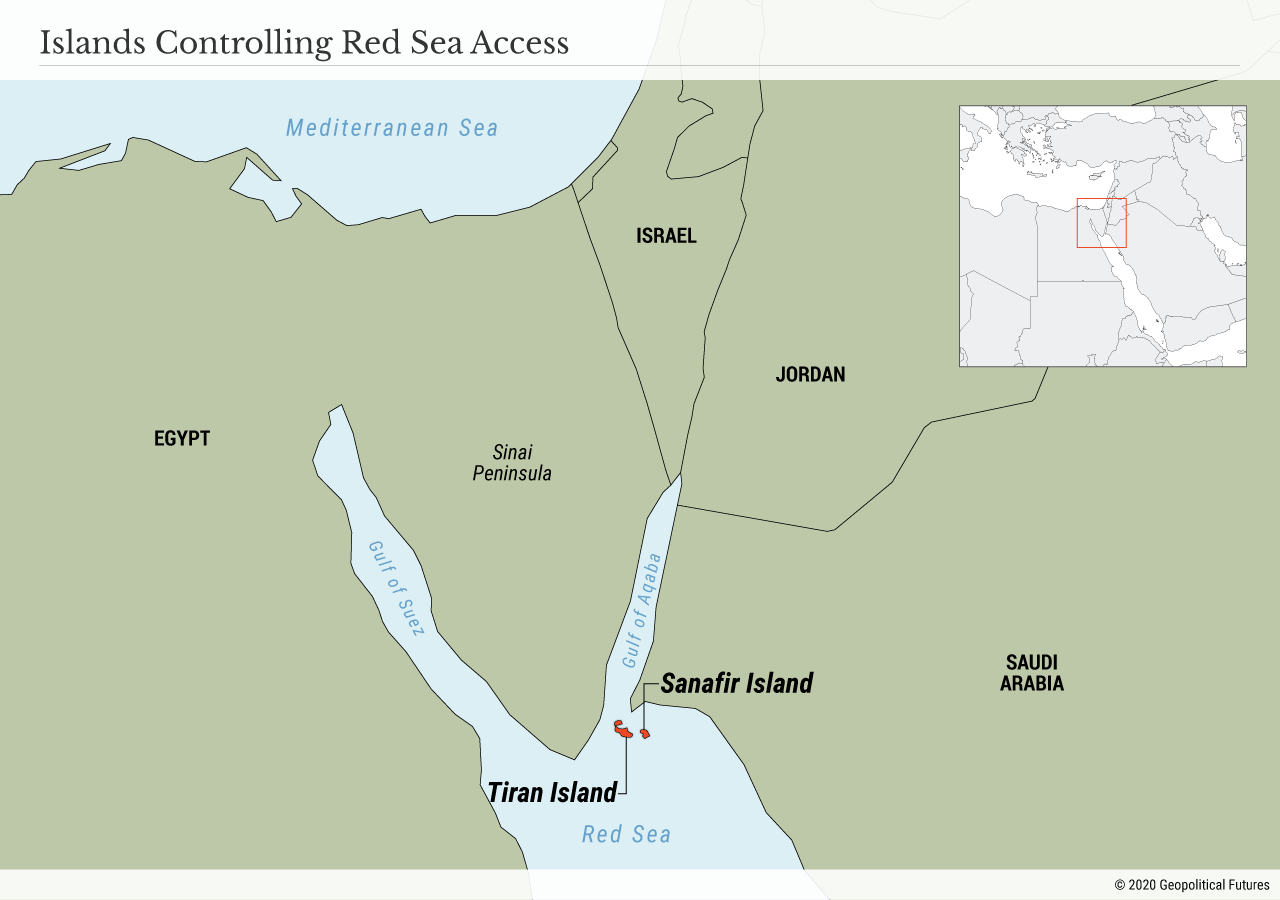

Nasser committed a gross miscalculation in 1967 by sending the army to Sinai without expecting war. He tried to restore the public’s confidence in him by closing the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, assuming that Johnson would not want to risk a regional war and would act to defuse the situation, as Eisenhower did in 1960 following Nasser’s mobilization of two Sinai divisions to the Israeli border to deter Israel from attacking Syria.

In 1960, however, Egyptian-Soviet relations were strained because of Nasser’s ban of the Syrian Communist Party following the formation of the United Arab Republic, which was welcome news in Washington.

In 1967, tensions between Nasser and Johnson were high, and Johnson chose not to stop Israel from launching the first strike.

Shift to Egyptian Nationalism

Israel’s spectacular victory in 1967 tarnished Nasser’s image. After Egypt accepted a cease-fire on June 8, 1967, Egyptian radio stations stopped playing pan-Arab music and instead played Egyptian patriotic songs, a shift that turned out to be permanent and reflected a fundamental inward-looking policy shift.

After Nasser died in 1970 from a heart attack at the age of 52, his successor, Anwar Sadat, faced opposition from Egypt’s leftists who wanted to control him, Islamists who tried to bring down the regime, and the Soviets, who were reluctant to provide him with offensive military hardware to cross the Suez Canal.

He pushed the two superpowers to address Israel’s occupation of Sinai more seriously but concluded that neither would come to Egypt’s defense. He then broke with the rest of the Arab world by signing the Camp David Accords with Israel in 1978. The next year, the Arab League suspended Egypt’s membership and relocated its headquarters to Tunis.

In 1981, Islamic militants assassinated Sadat during a military parade. His vice president, Hosni Mubarak, found himself too preoccupied with militant Islamists, who sought to topple the state and install an Islamic order, to take on Arab issues. Mubarak restructured the economy along crony capitalist lines and created a new class of neoliberal businesspeople.

He was focused on internal security and institutionalized Egypt’s relations with the U.S. to avoid crises. Even though Egypt lost its position as leader of the Arab world, Mubarak, a staunch Egyptian nationalist, maintained its autonomy in the regional order.

This situation changed under Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, who became president after the ouster of Mohammed Morsi in 2013. The cash-strapped economy necessitated alignment with the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

El-Sissi even ceded the islands of Tiran and Sanafir, which control access to the Red Sea from the Gulf of Aqaba, to Saudi Arabia. In 2017, el-Sissi joined Riyadh and Abu Dhabi in imposing a blockade on Qatar that is still ongoing.

Egypt has gone a long way, from a towering leader of Arabs to a follower of traditional Gulf leaders.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario