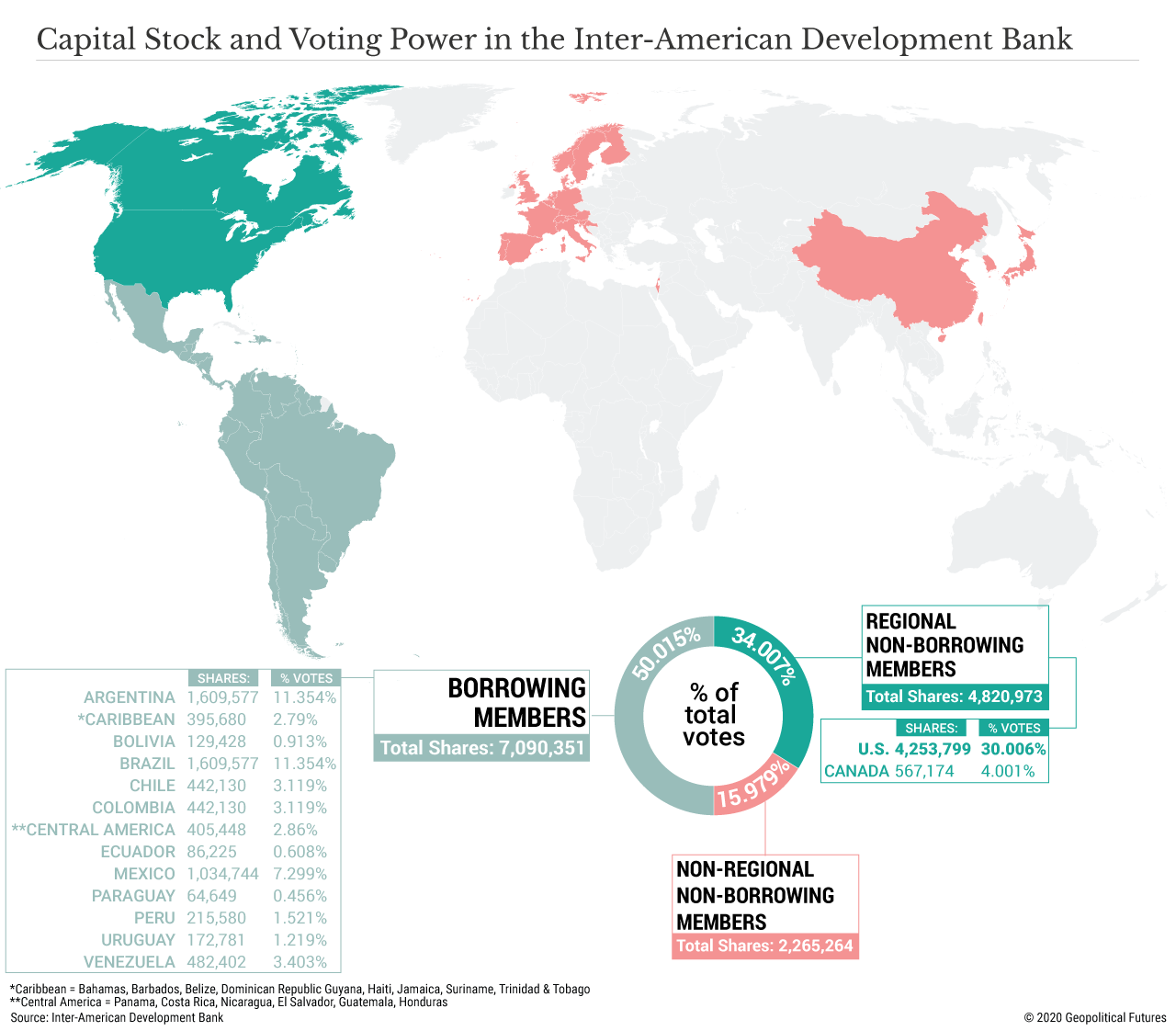

A few weeks ago, the head of the U.S.

National Security Council – not a State Department official, as would

normally be the protocol – introduced the Western Hemisphere Strategic

Framework, Washington’s new economic strategy for its half of the world,

while in Miami. Then, for the first time ever, Washington successfully

lobbied the Inter-American Development Bank to take on a U.S. official as

its head – a position typically reserved for non-U.S. and non-Brazilian

members who have less voting power in the bank. Later still, Secretary of

State Mike Pompeo made history as the first secretary to visit Suriname and

Guyana.

Developments such as these belie the

ordinarily passive approach the U.S. takes to managing relations with its

southern neighbors. Washington has long held the upper hand and so has

rarely needed to tinker with a system that works in its favor. But as it

debuts its new economic strategy for the region, it will resurrect memories

for countries that have been hurt by these kinds of initiatives in the

past. The U.S. may see new-found potential in its relationship with Latin

America, but the same cannot necessarily be said for Latin America.

A National Security Issue

The increase in the United States’

commercial interest in Latin America owes largely to a shift in focus from

military conflict in the Middle East to economic conflict with China (and,

to a lesser extent, Russia).

The U.S.-China trade war has changed

supply chain security from a purely economic issue to a national security

issue. In short, China’s role as a global manufacturing hub – especially

for medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, microchips and other electronics –

is now considered a threat. Consequently, Washington has begun to consider

new locations for U.S. companies whose factories are currently in China.

With its geographic proximity, relatively cheap labor force and firmly

established ties, Latin America is an obvious candidate.

(click to enlarge)

The potential relocation of factories

is as much a geopolitical question as it is an economic one. Companies

generally go where it makes the most economic sense, but when there are

geopolitical interests at stake, it is up to the governments to create

incentives and frameworks that compel other actors to produce the desired

results.

Washington’s latest hemisphere-wide

economic initiative, Back to the Americas, means to address mutual

economic-security needs, most notably by relocating U.S. manufacturing

companies to Latin America. The relocation would be supported by U.S.

investments in infrastructure in host countries that would, in theory,

drive economic growth. At the end of July, Mauricio Claver-Carone, then the

White House senior director for Western Hemisphere affairs and now the IDB

president, said that up to $50 billion in investments could enter the

region through Back to the Americas through the participation of four U.S.

government departments as well as the U.S. Agency for International

Development, the U.S. Trade and Development Agency, the U.S. International

Development Finance Corporation and the Export-Import Bank. It builds on

the Growth in the Americas initiative, which launched in 2018 and expanded

its scope in December 2019 to focus largely on using private sector

investment in infrastructure projects to create new jobs and increase

economic growth. A key component to achieving these goals is the reduction

of regulatory, legal, procurement and market barriers to investment by host

country governments.

(click to enlarge)

The timing is hardly coincidental:

China has steadily enlarged its economic footprint in Latin America over

the past two decades. Beijing used the region to help meet its demand for

hydrocarbons, metals and food supplies. From 2000 to 2019, Chinese trade with

the region grew from $12 billion to nearly $315 billion. It is currently

the top trade partner of Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Peru and Argentina. (In

every country except Argentina, China replaced the U.S.) According to the

Inter-American Dialogue, Chinese state loans to the region exceeded $140

billion from 2005 to 2019, though the amounts have significantly dropped

since 2015. China has also made substantial investments in mining and

agriculture, power generation, utilities and infrastructure, though again

the pace has slowed over the past three years.

The Back to the Americas initiative

aims to preserve the U.S. foothold in the region and keep foreign

competition at bay. The recently announced Western Hemisphere Strategic

Framework, however, rests on five pillars: securing the homeland, advancing

economic growth, promoting democracy and the rule of law, countering

foreign influence and strengthening alliances with like-minded partners. Relocating manufacturing to the Americas not only takes the supply chain

out of China’s hands but also helps diversify it. The finished products

made for U.S. consumption may also allow the U.S. to regain some of the

space it has lost to China in Latin America. If Washington can encourage

Latin American countries to create environments conducive to U.S. interests

by giving them money, there may be less need for Chinese financing and more

transparency with financial activities, and these countries can more easily

access funding from northern financial institutions.

What Washington Has to Offer

But U.S. ambitions will face several

obstacles. Local governments may find themselves in the uncomfortable

scenario of having to choose between Beijing or Washington, including over

how they adopt 5G technologies. Many will seek a balance that will allow

them to reap the benefits of siding with one without alienating the other.

Unlike China, the U.S. doesn’t have

state-owned enterprises that can do its bidding, or seemingly endless

discretionary spending for overseas projects. There will be some funding by

the U.S. government along with additional money from places like the IDB,

which contributes about $12 billion in infrastructure funding annually, but

private enterprise will play a greater role. The U.S. government can

incentivize companies, but it can’t force them to participate in its plans.

Companies could simply decide the market isn’t right for them.

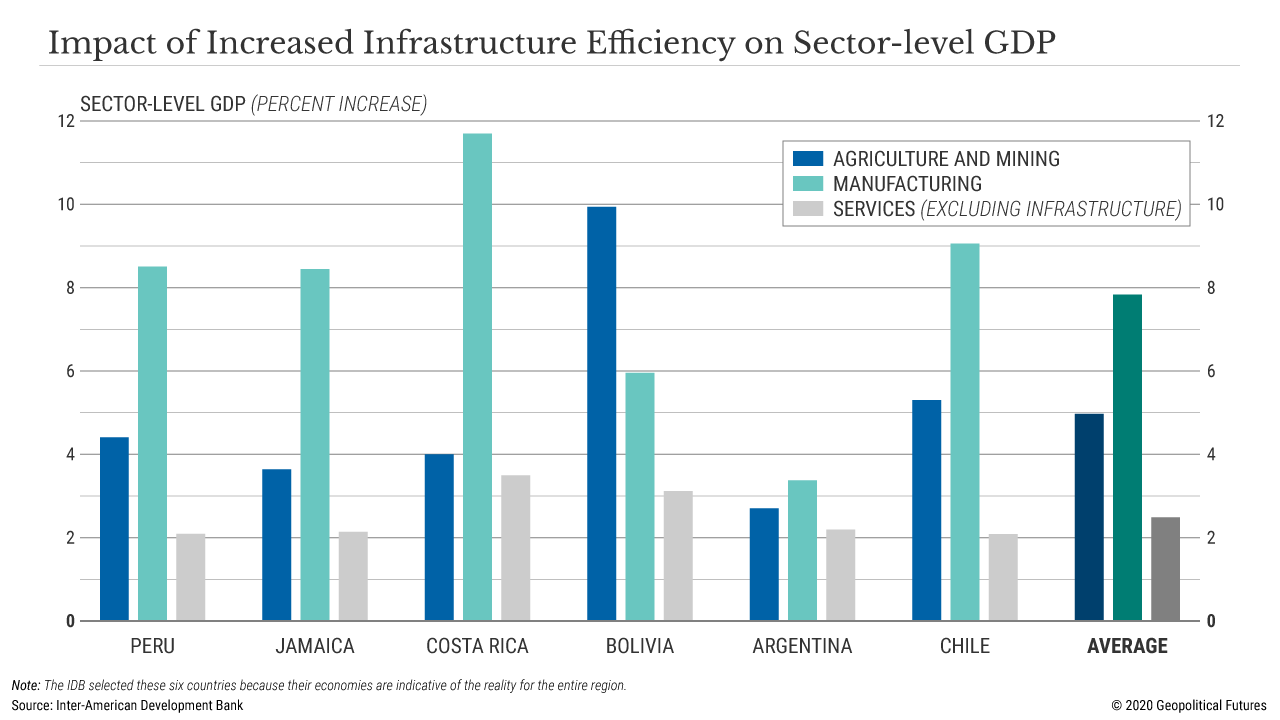

More importantly, the U.S. strategy

requires buy-in from participating countries. This is why it contains

provisions that may meet the region’s needs. By targeting infrastructure

projects, the U.S. is effectively addressing the long-standing economic

development challenge of huge infrastructure investment gaps faced by every

country in the region. A 2019 study by the IDB estimated that the region’s

infrastructure investment gap is the equivalent of 2.5 percent of gross

domestic product (roughly $150 billion) per year. U.S investments alone

can’t solve these problems, but neither can the host countries without

large outside capital injections, which U.S. companies can offer.

Infrastructure development also

addresses the region’s interest in improving its overall trade

competitiveness. Poor transportation and logistics facilities play a major

role in raising the price of domestically produced goods to the point that

they struggle to compete in global markets.

(click to enlarge)

Furthermore, the focus on manufacturing

aims to diversify the region’s economic activity away from natural resource

extraction. Reducing dependence on commodities would inoculate local

economies to price shocks and potentially lead to higher-value goods being

produced.

Not every Latin American country has

the same relationship with the U.S., of course, and those most likely to

participate will be countries that have traditionally allied with the U.S.

or whose economies are too integrated with the U.S. not to participate. Panama and Costa Rica, for example, are already working to address domestic

regulatory measures to meet U.S. requirements, while Ecuador admitted it

has an economic need to enact reforms that will facilitate economic

cooperation with the U.S.

The poster child for what this

initiative could look like in practice is Colombia, which is predisposed to keep a close

relationship with the U.S. and has already thrown its support

behind the project. Colombia’s ambassador to the U.S. openly acknowledged

that Bogota wants to benefit from U.S. nearshoring efforts and welcomes it

as an opportunity to reindustrialize. In some ways, it has been preparing

all year. In February, the government launched a new national logistics

policy that focuses on reducing logistics costs by simplifying bureaucratic

procedures and improving road and fluvial transportation infrastructure. The objective of the plan is to incentivize foreign direct investment,

boost exports and create economic opportunities. This was followed in the

summer by new tax breaks and other measures to attract up to $11.5 billion

in non-hydrocarbon foreign direct investment by 2022. In direct response to

Back to the Americas, ProColombia has conducted a targeted campaign to

identify companies interested in moving to Colombia from China.

Concerns

The U.S. has a long and complicated

history with Latin America when it comes to cooperation, particularly when

geopolitical agendas are so closely tied to economic ones There is a camp

that looks at increased U.S. interest in the region with skepticism. Though

they share a desire to see value-added goods hold a greater share of

exports, they believe the U.S. manufacturing initiative runs the risk of

producing low-value-added exports by exploiting local workforces. There is

also concern that increased trade with the U.S. could render the region a

depository for U.S. goods. Similar initiatives in the past have damaged

domestic industries in the region, prompting governments to pursue costly

import substitution schemes and to impose strict regulatory environments to

prop up local industry and employment.

The other major issue is that there are

strings attached. The U.S. government and companies alike will be looking

for certain security and political guarantees from their partners.

Ultimately, the ability to offer attractive investment environments to U.S.

investors will fall to the Latin American governments themselves. Past

instances where countries in the region have carried out reforms to

participate in U.S.-supported economic programs ended poorly. For example,

President John F. Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress purported to enhance

economic cooperation to improve Latin America’s per capita GDP, establish

democratic governments, achieve price stability, enact land reform and

improve other economic and social planning. Washington spent $1.4 billion

annually from 1962 to 1967 on this program but failed to produce the

desired economic development. Similarly, the Washington Consensus was

introduced to the region to help solve the debt crisis and boost growth. It

required countries to implement northern-formulated, structural economic

reforms that clashed with many of the region’s political and social

systems. This led to its failure and rejection, most notably in Argentina.

Hence why this is as much a

geopolitical initiative as an economic one. The economic question can be

answered only after there are clear sectors, projects and numbers to work

with. The current economic environment favors the U.S., but complicated

pasts are hard to overlook. All governments will also have to evaluate

participation in these plans against national needs. The fact that the U.S.

has renewed interest in the region has geopolitical significance

considering the U.S. has managed to muscle through its agenda but not with

strong results.

|

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario