The New Middle East Alliance

During his visit to Saudi Arabia in May 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump announced a plan to establish the Middle East Strategic Alliance, a group ostensibly meant to combat terrorism but in reality meant to counter Iran.

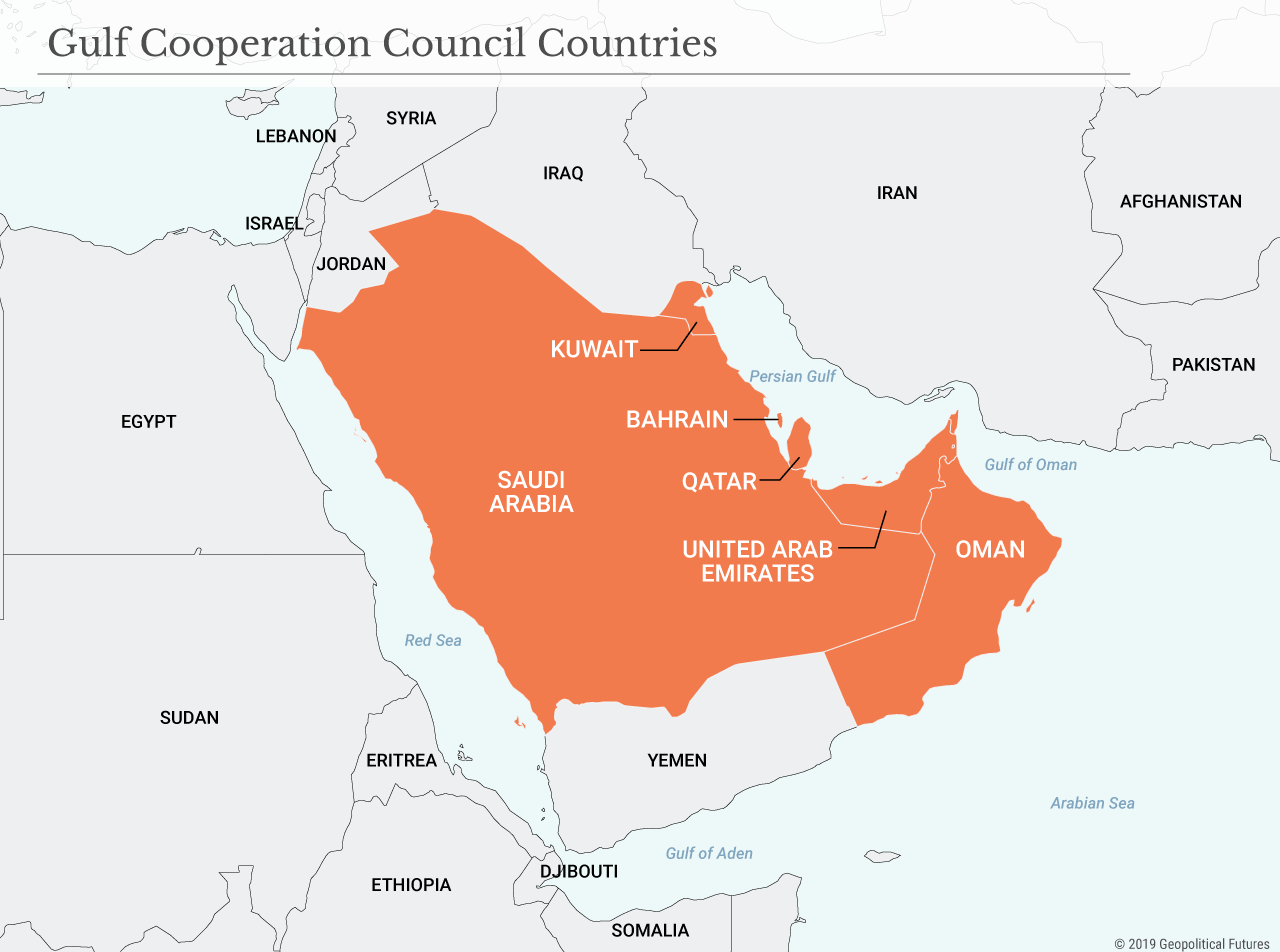

The plan would have comprised the Gulf Cooperation

Council, Jordan, Egypt and the United States, but after Egypt withdrew in 2019

over objections to joining a military pact arrayed against Iran, momentum for

the alliance died.

But now it’s back, courtesy of the recent peace accords that normalized Israel's relations with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. The U.S. expects Israel and the UAE to play a crucial role in the new alliance, which will likely attract additional Arab countries.

However, the

complexity of Middle Eastern politics makes it unlikely for the new coalition

to take off, not only because regional powers – such as Turkey, Iran and Egypt

– will oppose it but because Israel and the UAE have different agendas for

getting into it in the first place.

The UAE and Saudi Perspectives

After the first Gulf War, the GCC signed the 1992 Damascus Declaration with Egypt and Syria to defend the Gulf states against foreign attacks. The deal floundered, though, because the Saudis eventually decided it was better for them to develop their own military capabilities rather than invite foreign troops onto their shores.

The war in

Yemen has shown the failure of Saudi Arabia to build a competent military that

can defend the country, let alone venture outside its national borders.

Saudi policy has always eschewed military involvement outside the Arabian Peninsula and instead focused on domestic stability, security and predominance in the GCC. (In 1950, it even leased two islands in the Red Sea to Egypt so that it could abstain from hostility against Israel.)

The spread of Iranian influence to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen, however, directly threatens Saudi Arabia, which worried that it would be next in line if Middle Eastern governments were to fall. Bahrain's minister of foreign affairs, whose statements usually echo the official Saudi position, made it clear that the primary reason for signing a peace treaty with Israel was his country's quest for security vis-a-vis Iran.

As for the Saudi royals, when

the Trump administration declined to answer Iran's attacks in 2019 on two

Aramco oil facilities, they began to think twice about their security

relationship. They concluded they could no longer rely on American protection

and, therefore, needed a new partner.

The UAE has two primary security reasons for signing a peace accord with Israel. First, its leader, Mohammed bin Zayed, is unsure about the future of the Saudi government. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has antagonized senior members in the royal family, the religious establishment and the National Guard.

If MBS were forced out, it would expose the UAE’s western flank. MBZ wants to nip this in the bud by partnering with a strong ally like Israel. The UAE reasons that the Israel vs. Iran conflict will end sooner or later.

When it ends, the two countries will resume their strong ties of friendship and cooperation that were disrupted by Iran’s 1979 revolution, exposing the UAE's eastern flank because Israel considers Iran an established power and prefers to foster a strategic relationship with it instead of the small and new UAE state.

MBZ does not want to leave the

Emirates' fate to chance and prefers to be proactive rather than reactive.

And to be clear, it is very much a matter of security. In fact, the UAE exaggerates the financial benefits of the peace deal. Business transactions with the UAE probably won’t exceed $6.5 billion, which would not add much to the wealthy UAE economy. It cannot contribute to the high-tech and Western-style Israeli economy, whose exports exceeded $114 billion in 2019.

The fact that the director of Israeli intelligence drafted the

accord articles suggests that security is the basis for cooperation, just as it

was with Egypt, Jordan and the Palestine Liberation Organization.

The Israeli Position

Strategically, peace between Israel and the GCC adds little to regional stability because it involves countries that do not share borders – and that are not even at war. The only Gulf state that existed at the time of Israel's establishment in 1948 was Saudi Arabia, which had neither a developed government nor a standing army.

But the move makes a little more sense for Israel, which never really abandoned the concept of David Ben-Gurion's 1950 Alliance of the Periphery, which he struck with Turkey, Iran and Ethiopia.

The Arab world may be in turmoil for the foreseeable future, but

the periphery was less so. Relations with them were smooth, predictable and

unencumbered with ideology or notions of fairness and justice, and seem likely

to make a strong comeback.

Israel's diplomatic relations with Iran have been bad for the past four decades, but there is no reason to think they will be bad forever. Despite exchanging threats, relations between Iran and Israel are far from hostile.

Dozens of Israeli companies, mostly in the energy and agriculture sectors, operate in Iran directly or via subsidiaries. Israeli businesses buy Iranian marble, nuts and dried fruit through agents in Turkey and Jordan. During its war with Iraq in the 1980s, Iran turned to Israel for weapons. In 1987, former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin described Iran as "Israel's best friend."

His remark was not random and driven by the spur of the moment. Historical relations did not intend Iran and Israel to be enemies. Jews have lived in Iran without interruption since their emancipation from Babylonian rule by Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid Empire in the sixth century B.C. and allowed them to return to Jerusalem. Iranian Jews helped Cambyses II defeat the Egyptians in the Battle of Pelusium in 525 B.C.

The 10,000 Jews still living in Iran are served by more than 100 active

synagogues, whereas millions of Sunnis living in major Iranian cities are not

allowed to build mosques Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

personally sees to it that the Jewish community receives fair treatment. In

2015, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif said there was no inherent

problem with Israel and that Iran would be willing to exchange diplomatic

missions with the Jewish state if it agreed to establish a Palestinian state.

Iran views Israel as a representative of the West. Iranian Jews living in the U.S. use their influence to prevent attacks on Iran because of its nuclear and long-range missile programs. Israeli politician Shaul Mofaz, born in Tehran, staunchly opposed striking Iranian atomic facilities when he was minister of defense from 2002 to 2006. The ongoing conflict between Israel and Iran is not about recognition, as it is with Arabs, but about regional power status and influence.

Israel needs Arabs

to recognize its legitimacy, and Iran wants Israel to accept it as a partner on

equal footing. The Iranians believe the West and czarist Russia humiliated them

over the past two centuries. They want to reclaim their glorious past, and, at

heart, they do not view Israel as their enemy.

Gulf Arabs want peace with Israel because they are afraid of Iran and because it is what the U.S. wants. But if they believe Israel will defend them against Iran, they should think again. In 2017, Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz revealed a well-known secret about his country's relations with Arab and Islamic countries.

He said that "the one who wants

those ties to be discreet is the other side." Israel is keen on bringing

these relations out into the open to become accepted by the public. It is

uncomfortable with maintaining discreet ties with Arabs because it creates a

sense of embarrassment, hardly a good foundation on which to build lasting

relations. The Iranians would behave differently in the event of peace.

Unlike the UAE, Israel lacks the motivation to become involved in the region's counterrevolutions, and it does not expect to benefit much from expanding its economic transactions with the GCC. Israel is interested in consolidating its legitimacy in the Middle Eastern regional order by making friends, not enemies.

Regional Outlook

U.S. presidents having problems at home tend to occupy themselves with foreign issues either as a distraction or as a way to improve their public opinion ratings. Media reports frequently link Trump's Middle East peace drive to an effort to galvanizing his evangelical base of support ahead of the forthcoming presidential election. But the desire to win a second presidential term is insufficient to account for the Trump administration's push for peace.

Indeed, the frenzy to sign treaties between

Israel and peripheral Arab countries is not about peace. Instead, it is mostly

about building a military alliance to activate Washington's new

offshore-balancing doctrine and ensure that no anti-American hegemon would rise

in the Middle East. The U.S. has no intention to quit the region, but it wants

to redefine its core interests and avoid significant military deployment there.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario